Flashback Friday.

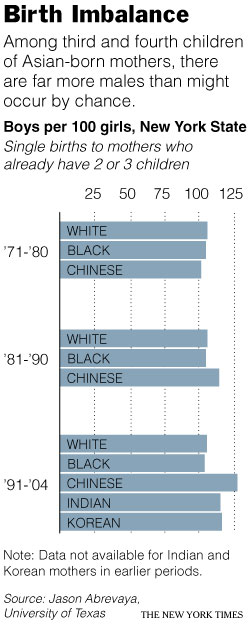

A New York Times article broke the story that a preference for boy children is leading to an unlikely preponderance of boy babies among Chinese-Americans and, to a lesser but still notable extent, Korean- and Indian-Americans.

Explaining the trend, Roberts writes:

In those families, if the first child was a girl, it was more likely that a second child would be a boy, according to recent studies of census data. If the first two children were girls, it was even more likely that a third child would be male.

Demographers say the statistical deviation among Asian-American families is significant, and they believe it reflects not only a preference for male children, but a growing tendency for these families to embrace sex-selection techniques, like in vitro fertilization and sperm sorting, or abortion.

The article explains the preference for boy children as cultural, as if Chinese, Indian, and Korean cultures, alone, expressed a desire to have at least one boy child. Since white and black American births do not show an unlikely disproportion of boy children, the implication is that a preference for boys is not a cultural trait of the U.S.

Actually, it is.

In 1997 a Gallup poll found that 35% of people preferred a boy and 23% preferred a girl (the remainder had no preference). In 2007 another Gallup poll found that 37% of people preferred a boy, while 28% preferred a girl.

I bring up this data not to trivialize the preference for boys that we see in the U.S. and around the world, but to call into question the easy assumption that the data presented by the New York Times represents something uniquely “Asian.”

Instead of emphasizing the difference between “them” and “us,” it might be interesting to try to think why, given our similarities, we only see such a striking disproportionality in some groups.

Some of the explanation for this might be cultural (e.g., it might be more socially acceptable to take measures to ensure a boy-child among some groups), but some might also be institutional. Only economically privileged groups have the money to take advantage of sex selection technology (or even abortion, as that can be costly, too). Sex selection, the article explains, costs upwards of $15,000 or more. Perhaps not coincidentally, Chinese, Korean, and Indian Asians are among the more economically privileged minority groups in the U.S.

Instead of demonizing Asian people, and without suggesting that all groups have the same level of preference for boys, I propose a more interesting conversation: What enables some groups to act on a preference for boys, and not others?

Originally posted in 2009.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.