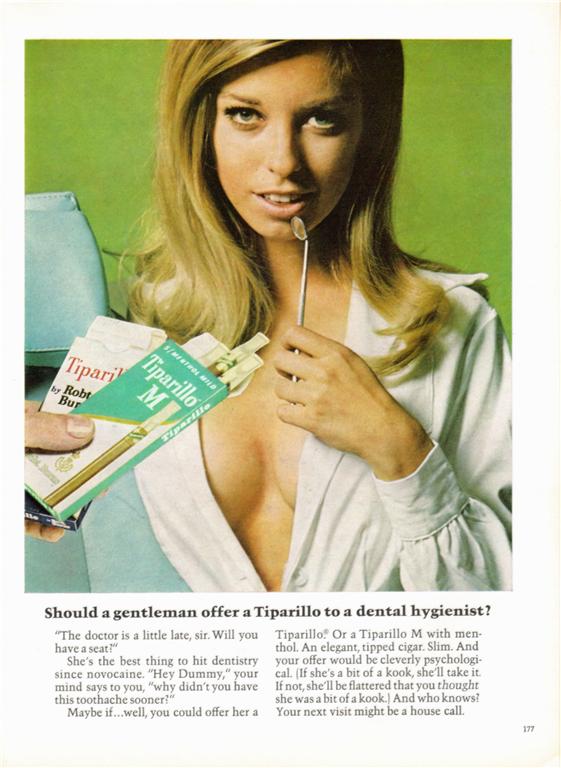

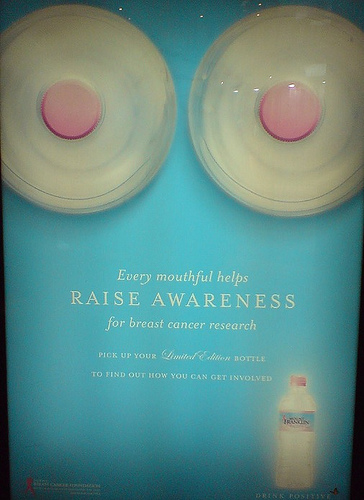

The sexualized campaign against breast cancer (i.e., “save the tatas”) is fascinating. Why should we care about breast cancer? Because we think boobs are hot and we like to put them in our mouths.

I think it’s the ad companies that win. This bottled water advertisement (found here) gets to be simultaneously socially conscious and titillating:

Also in breast cancer awareness and advertising: if men had boobs, they’d care about breast cancer, gender symbolism in breast cancer ads, and objectification in the service of breast cancer awareness.

Also don’t miss boobsboobsboobsboobsboobsboobsboobsboobsboobs.