In honor of yesterday’s game, we’re re-posting two of our favorite football-related posts. This one and one about a young team that confused its opponent by deviating from the football script without breaking the rules.

In “Televised Sport and the (Anti)Sociological Imagination,” Dan C. Hilliard discusses the rigid segmentation of televised sports programs, a schedule that in some cases requires “television timeouts”–that is, timeouts in the game due primarily to the need to break up the broadcast for commercials. Televised sports programs and advertising have become increasingly intertwined, such that they’re often nearly indistinguishable, what with the frequent mention of sponsors’ products by sports commentators.

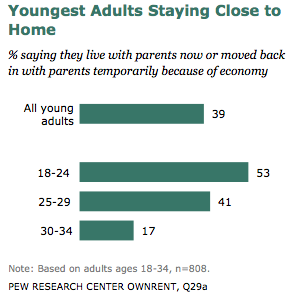

In this video from the Wall Street Journal, a journalist talks about the results of a study he completed in which he timed every element of a large number of televised football (as in American football, not soccer) games. The results? In a typical 3-hour broadcast, barely over 10 minutes shows action on the field. What makes up the rest? Well, advertising, of course, but even aside from that, most of the game coverage is made up of replays, players standing around or huddling before plays, shots of coaches or the crowd, and about 3 seconds of cheerleaders:

A breakdown of game coverage:

Here’s a breakdown of the amount of time spent on each element for a bunch of specific games.

Of course, in some cases these breaks in the action are an integral part of the game. But as things such as television timeouts show, games may also be intentionally slowed down to be sure the game fills the allotted time slot… and provides plenty of time for all the advertising they sold during it.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.