Larry Harnisch, of L.A.’s The Daily Mirror, let us know that 4th Estate analyzed the racial and ethnic breakdown of reporters covering the presidential election for 38 major print media outlets. The analysis included front-page articles published between January 1st and October 12th of this year.

Here’s the key for all of the following images:

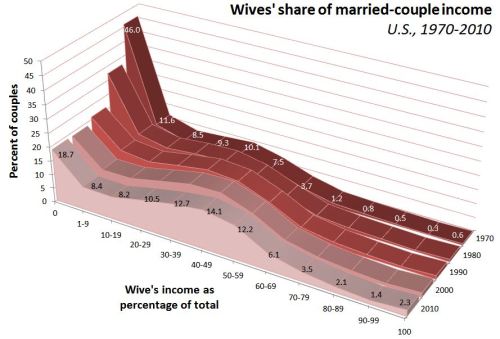

For every major topic, the overwhelming majority of front-page articles were written by non-Hispanic Whites, while racial/ethnic minorities were underrepresented compared to the overall U.S. population:

Major newspapers varied in the diversity of those writing their feature articles. The Dallas Morning News was the most diverse, with a particularly large percentage (18.8) of front-page stories written by African American reporters. The San Francisco Chronicle had the least diversity; 100% of its feature political stories were written by White non-Hispanics:

Overall, 93% of the feature articles analyzed in the database were written by White non-Hispanics, 4% by Asian Americans, about 2% by African Americans, and less than 1% by Hispanics. Compare that with each group’s proportion of the overall U.S. population:

These numbers clearly matter in terms of career opportunities and exposure for minorities within the industry. But they also should concern us readers. What does the lack of diversity mean in terms of the issues covered, the political contacts and average-Joe-voters spoken to, the topics seen as important enough to cover?

Also see our earlier post on the gender of those quoted in news stories about the election.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.