Despite, well, everything, we are trying to get back into the classroom as much as we can at the start of a new academic year. I am scheduled to teach Introduction to Sociology for the first time this coming spring and planning the course this fall.

Whether in person or remote, I will be ecstatic to introduce our field to a new batch of students — to show them what sociologists do, how we work, and how we think about the world. Thinking about those foundations, the start of an academic year is a great time to come back and ask “what, exactly, are we doing?”

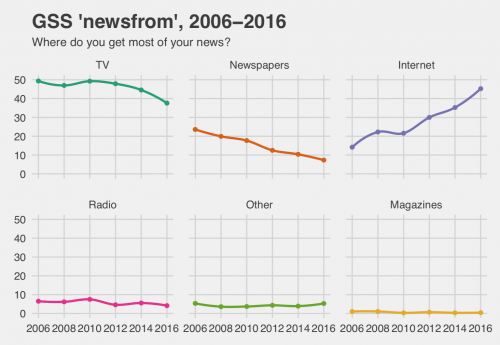

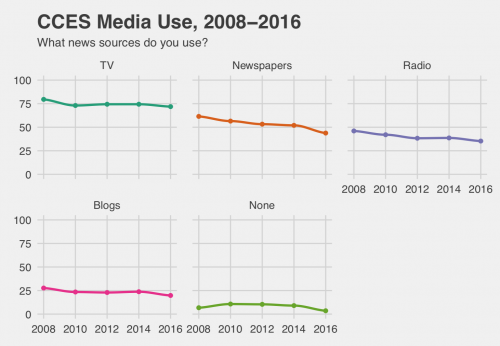

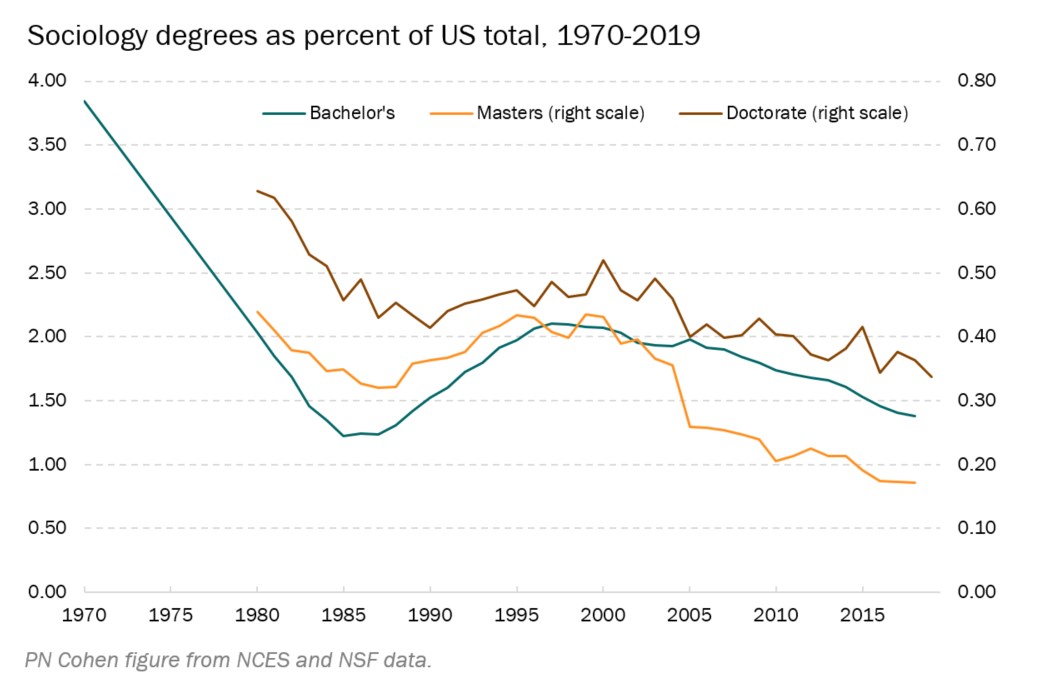

I have been thinking a lot about that question in our current chaotic moment and in the context of sociology’s changing role in higher eduction. This chart made by Philip Cohen keeps coming to mind:

There are a lot of reasons for the decline in sociology majors, and reflections on our purpose as a field are not new at all (examples here, here, here, and on the social sciences in general here). We all bring different ideas about our common methods and missions, and our field has plenty of room for many different sociologies. I like big-tent approaches like the one here at The Society Pages.

For newcomers, though, that range makes it hard to grasp what sociologists actually do, and that makes it tough to do right by our students. At some point, someone is going to ask a new sociology major the dreaded question: “what do you do with that?” I think we have a responsibility to model ways to answer that question clearly and directly, even if we don’t want to lock students into narrow careerist ambitions. A wonky answer about ~society~ doesn’t necessarily help them.

That’s why I love these recent podcast episodes with Zeynep Tufekci. In each case, the hosts ask her how she got so much right about COVID-19 so early in the pandemic. In both, her answers explicitly show us how insights about relationships, organizations, and stigma helped to guide her thinking. These interviews are a model for showing us what sociological thinking actually can do to address pressing issues.

Far too often, our institutions miss out on the benefits of thinking about social systems and relationships in this way. Sources like these help to sell sociology to our students, and they will be a big part of my upcoming intro course. In the coming weeks, we’ll be running more posts that focus on going back to basics for newcomers in sociology, including updates to our “What’s Trending?” series and more content for the intro classroom. Stay tuned, and share how you sell sociology to your students!

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.