It’s an American tradition. In fact, FBI data on background checks suggests that more guns were given as Christmas gifts last year than any previous year (source). One-and-a-half million background checks were ordered in December 2011, more than any other month in American history. Data from 2012 shows another uptick.

Notably, these data represent an increase in the number of guns at the same time as we see a decrease in the number of gun owners. “[F]ewer and fewer people are owning more and more guns,” explained Caroline Brewer, representing the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.

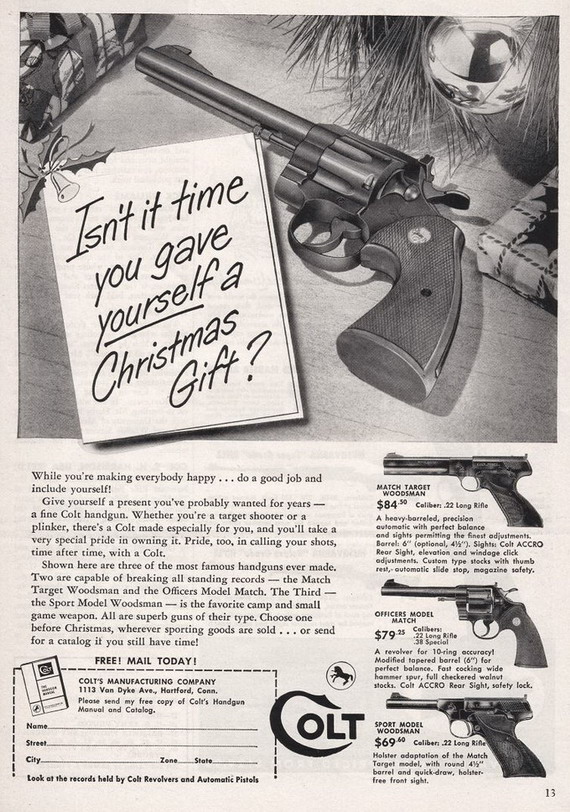

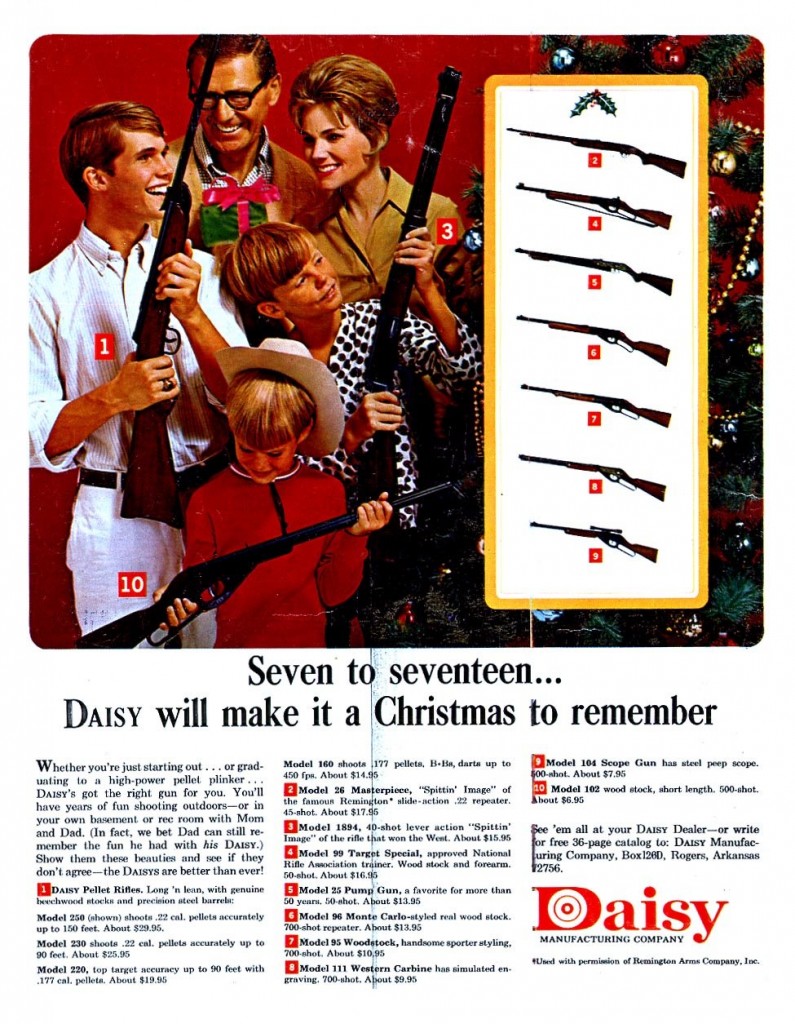

1939 (source):

Date unknown (source):

Date unknown (source):

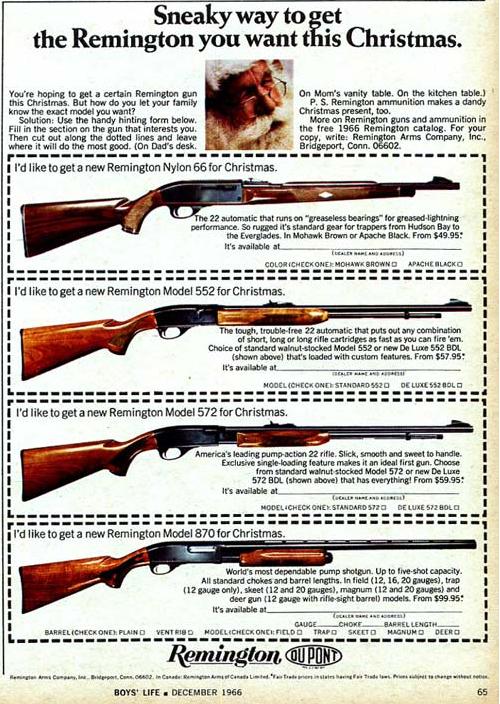

1966 (source):

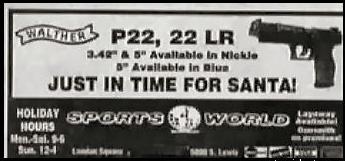

Online now (source):

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.