Saturday night, I went to the 7:30 showing of “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl.” The movie had just opened, so I went early. I didn’t want the local teens to grab the all the good seats – you know, that thing where maybe four people from the group are in the theater but they’ve put coats, backpacks, and other place markers over two dozen seats for their friends, who eventually come in five minutes after they feature has started.

That didn’t happen. The theater (the AMC on Broadway at 68th St.) was two-thirds empty (one-third full if you’re an optimist), and there were no teenagers. Fox Searchlight, I thought, is going to have to do a lot of searching to find a big enough audience to cover the $6 million they paid for the film at Sundance. The box office for the first weekend was $196,000 which put it behind 19 other movies.

But don’t write off “Me and Earl” as a bad investment. Not yet. According to a story in Variety, Searchlight is looking that “Me and Earl” will be to the summer of 2015 what “Napoleon Dynamite” was to the summer of 2004. Like “Napoleon Dynamite,” “Me and Earl” was a festival hit but with no established stars and debt director (though Gomez-Rejon has done television – several “Glees” and “American Horror Storys”). “Napoleon” grossed only $210,000 its first week, but its popularity kept growing – slowly at first, then more rapidly as word spread – eventually becoming cult classic. Searchlight is hoping that “Me and Earl” follows a similar path.

The other important similarity between “Napoleon” and “Earl” is that both were released in the same week as a Very Big Movie – “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban” in 2004, “Jurassic World” last weekend. That too plays a part in how a film catches on (or doesn’t).

In an earlier post I graphed the growth in cumulative box office receipts for two movies – “My Big Fat Greek Wedding” and “Twilight.” The shapes of the curves illustrated two different models of the diffusion of ideas. In one (“Greek Wedding”), the influence came from within the audience of potential moviegoers, spreading by word of mouth. In the other (“Twilight”), impetus came from outside – highly publicized news of the film’s release hitting everyone at the same time. I was working from a description of these models in sociologist Gabriel Rossman’s Climbing the Charts.

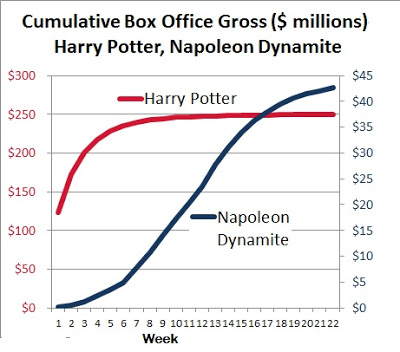

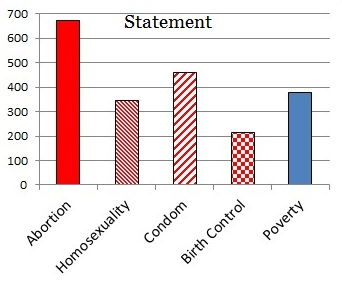

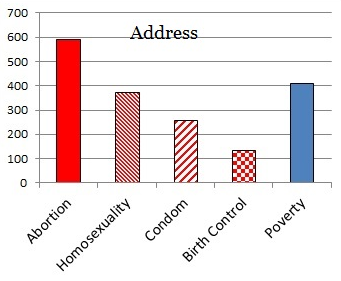

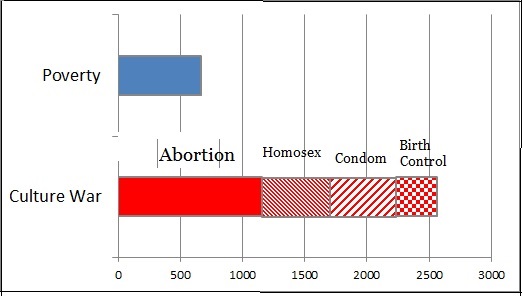

You can see these patterns again in the box office charts for the two movies from the summer of 2004 – “Harry Potter/Azkaban” and “Napoleon Dynamite.” (I had to use separate Y-axes in order to get David and Goliath on the same chart; data from BoxOfficeMojo.)

“Harry Potter” starts huge, but after the fifth week the increase in total box office tapers off quickly. “Napoleon Dynamite” starts slowly. But in its fifth or sixth week, its box office numbers are still growing, and they continue to increase for another two months before finally dissipating. The convex curve for “Harry Potter” is typical where the forces of influence are “exogenous.” The more S-shaped curve of “Napoleon Dynamite” usually indicates that an idea is spreading within the system.

But the Napoleon curve is not purely the work of the internal dynamics of word-of-mouth diffusion. The movie distributor plays an important part in its decisions about how to market the film – especially when and where to release the film. The same is true of “Harry Potter.”

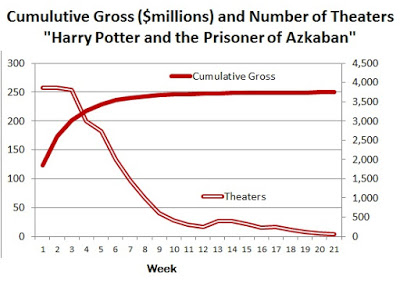

The Warner Bros. strategy for “Harry Potter” was to open big – in theaters all over the country. In some places, two or more of the screens at the multi-plex would be running the film. After three weeks, the movie began to disappear from theaters, going from 3,855 screens in week #3 to 605 screens in week #9.

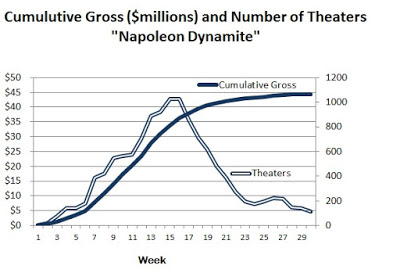

“Napoleon Dynamite” opened in only a small number of theaters – six to be exact. But that number increased steadily until by week #17, it was showing in more than 1,000 theaters.

It’s hard to separate the exogenous forces of the movie business from the endogenous word-of-mouth – the biz from the buzz. Were the distributor and theater owners responding to an increased interest in the movie generated from person to person? Or were they, through their strategic timing of advertising and distribution, helping to create the film’s popularity? We can’t know for sure, but probably both kinds of influence were happening. It might be clearer when the economic desires of the business side and the preferences of the audience don’t match up, for example, when a distributor tries to nudge a small film along, getting it into more theaters and spending more money on advertising, but nobody’s going to see it. This discrepancy would clearly show the influence of word-of-mouth; it’s just that the word would be, “don’t bother.”

Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.