Cross-posted at Family Inequality.

The Pew Research Center put out a report this month titled, “Modern Parenthood: Roles of Moms and Dads Converge as They Balance Work and Family,” written by Kim Parker and Wendy Wang. It analyzes trends in time use among men and women in families, showing the big changes since the 1960s, and adds Pew’s own survey data on attitudes and perceptions. Lots of interesting information.

But what jumped out at me was that the stall in progress did not feature much in Pew’s narrative. I really noticed that when the Joy Cardin show featured the report on Wisconsin Public Radio, and Cardin’s intro was this:

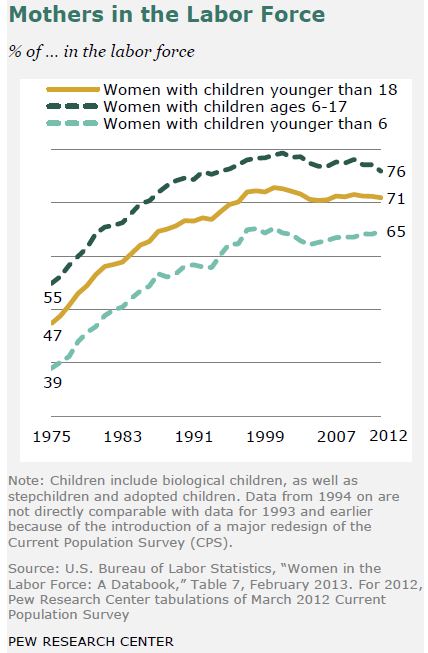

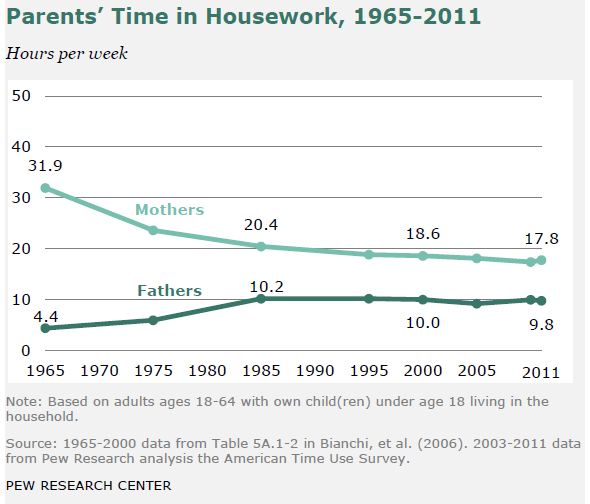

Family gender roles are converging, according to a new survey from the Pew Research Center. Father’s have more than doubled the time they spend on housework. More moms are paid to work outside the home (audio here).

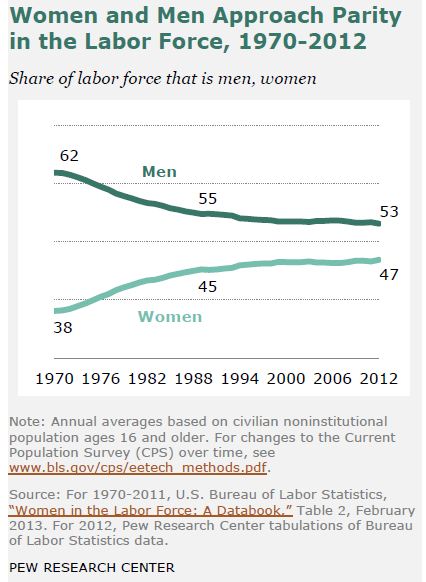

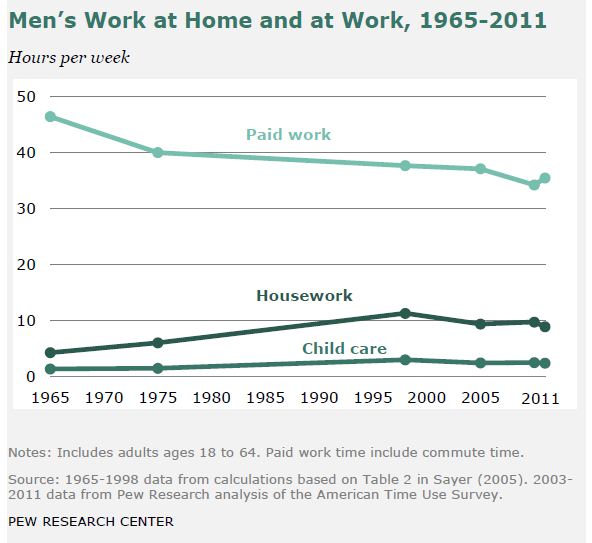

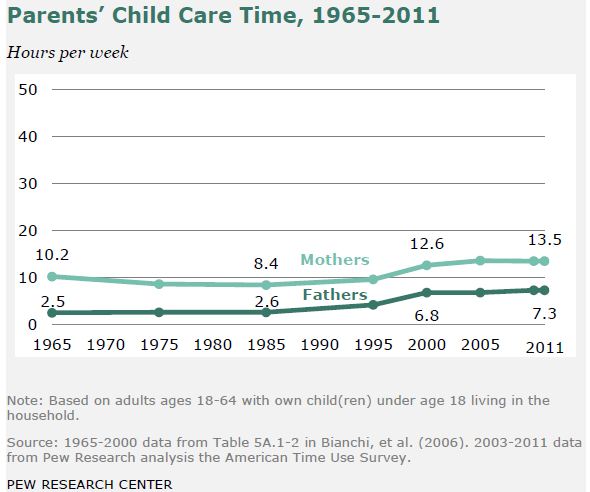

Those facts are true, but old news — older than the new news, which is that nothing much has happened since the early 1990s. Here are the trends, in Pew’s nice graphics. See if you can find the stall point in each figure.

******

******  ******

******  ******

******  ******

******  ******

******

The last one, parents’ child care time, is the only one that shows continued real progress, albeit slower, in the last decade.

I favor three explanations for this gender stall:

- Work-family policy that encourages specialization in domestic or labor force roles, as described by Stephanie Coontz here.

- Cultural trends toward “egalitarian essentialism,” which “blends aspects of feminist equality and traditional motherhood roles” (e.g., intensive parenting mania), as described by David Cotter, Joan Hermsen and Reeve Vanneman here.

- Weaker government enforcement of anti-discrimination law, as described in the new book Documenting Desegregation, by Don Tomaskovic-Devey and Kevin Stainback.

These explanations do not exclude others.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.