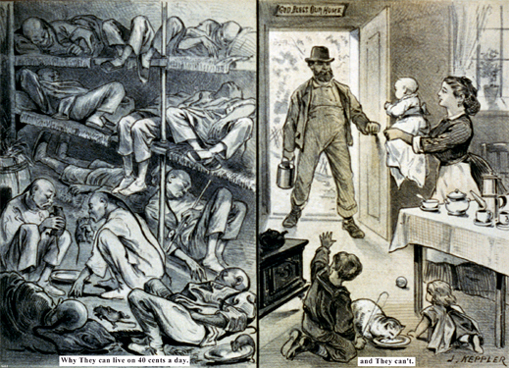

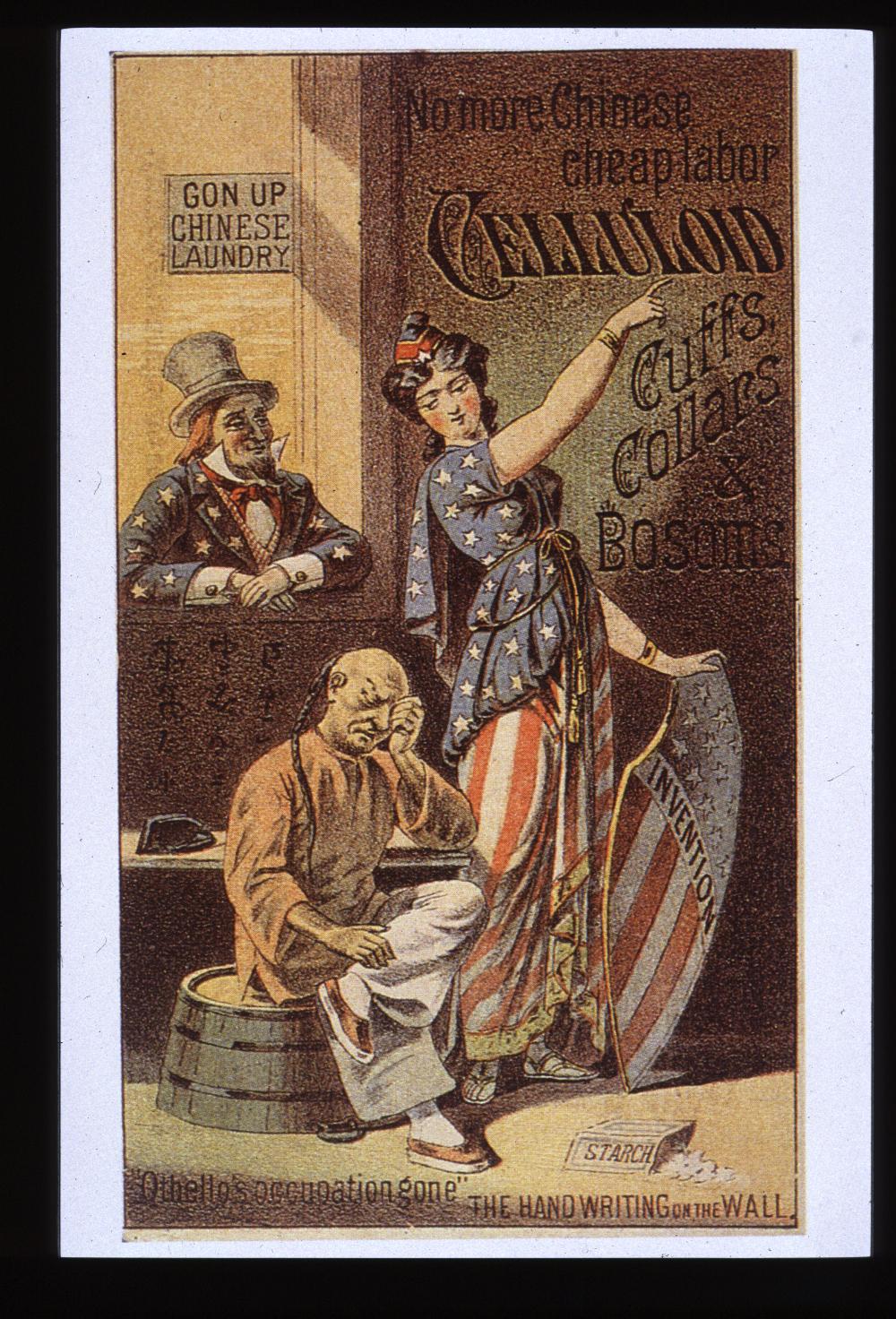

There is one similarity between the Israel/Gaza crisis and the U.S. unaccompanied child immigrant crisis: National borders enforcing social inequality. When unequal populations are separated, the disparity creates social pressure at the border. The stronger the pressure, the greater the military force needed to maintain the separation.

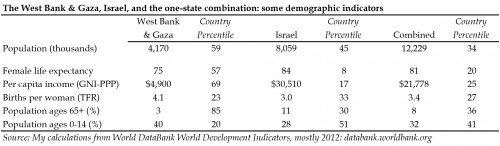

To get a conservative estimate of the pressure at the Israel/Gaza border, I compared some numbers for Israel versus Gaza and the West Bank combined, from the World Bank (here’s a recent rundown of living conditions in Gaza specifically). I call that conservative because things are worse in Gaza than in the West Bank.

Then, just as demographic wishful thinking, I calculated what the single-state solution would look like on the day you opened the borders between Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. I added country percentiles showing how each state ranks on the world scale (click to enlarge).

Israel’s per capita income is 6.2-times greater, its life expectancy is 6 years longer, its fertility rate is a quarter lower, and its age structure is reversed. Together, the Palestinian territories have a little more than half the Israeli population (living on less than 30% of the land). That means that combining them all into one country would move both populations’ averages a lot. For example, the new country would be substantially poorer (29% poorer) and younger than Israel, while increasing the national income of Palestinians by 444%. Israelis would fall from the 17th percentile worldwide in income, and the Palestinians would rise from the 69th, to meet at the 25th percentile.

Clearly, the separation keeps poor people away from rich people. Whether it increases or decreases conflict is a matter of debate.

Meanwhile

Meanwhile, the USA has its own enforced exclusion of poor people.

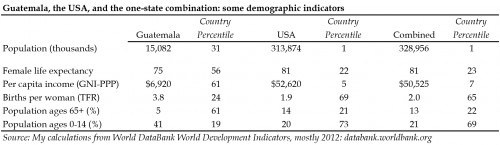

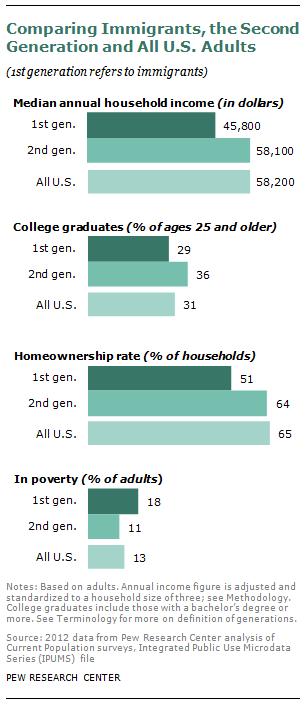

The current crisis at the southern border of the USA mostly involves children from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. They don’t actually share a border with the USA, of course, but their region does, and crossing into Mexico seems pretty easy, so it’s the same idea.

To make a parallel comparison to Israel and the West Bank/Gaza, I just used Guatemala, which is larger by population than Honduras and El Salvador combined, and also closest to the USA. The economic gap between the USA and Guatemala is even larger than the Israeli/Palestinian gap. However, because the USA is 21-times larger than Guatemala by population, we could easily absorb the entire Guatemalan population without much damaging our national averages. Per capita income in the USA, for example, would fall only 4%, while rising more than 7-times for Guatemala (click to enlarge):

This simplistic analysis yields a straightforward hypothesis: violence and military force at national borders rises as the income disparity across the border increases. Maybe someone has already tested that.

The demographic solution is obvious: open the borders, release the pressure, and devote resources to improving quality of life and social harmony instead of enforcing inequality. You’re welcome!

Cross-posted at Family Inequality.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.