Flashback Friday.

Is it true that Spanish-speaking immigrants to the United States resist assimilation?

Not if you judge by language acquisition and compare them to earlier European immigrants. The sociologist Claude S. Fischer, at Made in America, offers this data:

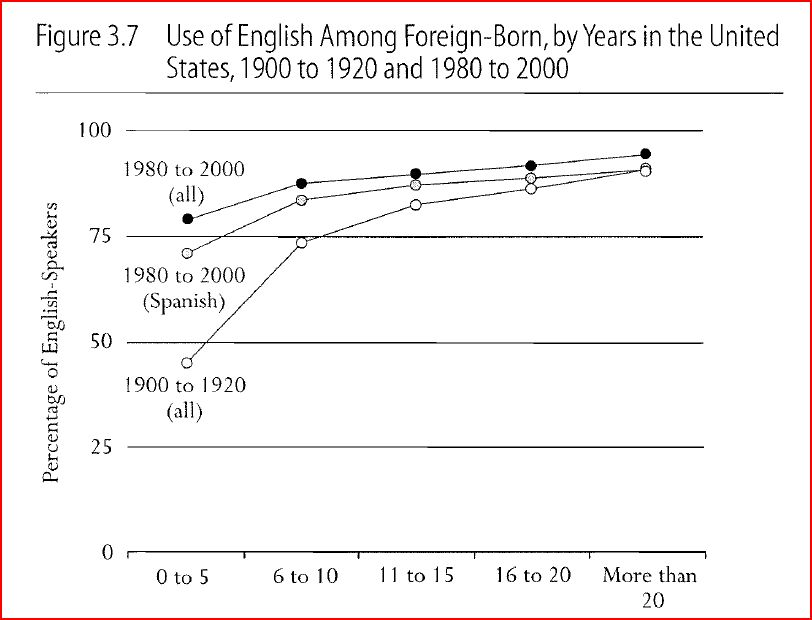

The bottom line represents the percentage of English-speakers among the wave of immigrants counted in the 1900, 1910, and 1920 census. It shows that less than half of those who had been in the country five years or less could speak English. This jumped to almost 75% by the time they were here six to ten years and the numbers keep rising slowly after that.

Fast forward 80 years. Immigrants counted in the 1980, 1990, and 2000 Census (the top line) outpaced earlier immigrants by more than 25 percentage points. Among those who have just arrived, almost as many can speak English as earlier immigrants who’d been here between 11 and 15 years.

If you look just at Spanish speakers (the middle line), you’ll see that the numbers are slightly lower than all recent immigrants, but still significantly better than the previous wave. Remember that some of the other immigrants are coming from English-speaking countries.

Fischer suggests that the ethnic enclave is one of the reasons that the wave of immigrants at the turn of the 20th century learned English more slowly:

When we think back to that earlier wave of immigration, we picture neighborhoods like Little Italy, Greektown, the Lower East Side, and Little Warsaw – neighborhoods where as late as 1940, immigrants could lead their lives speaking only the language of the old country.

Today, however, immigrants learn to speak with those outside of their own group more quickly, suggesting that all of the flag waving to the contrary is missing the big picture.

Originally posted in 2010.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.