Cross-posted at Scientopia.

One year ago today six black teenagers died in the Louisiana Red River. They were wading in waist deep water when one, 15-year-old DeKendrix Warner, fell off an underwater ledge. He struggled to swim and, one by one, six of his cousins and friends jumped in to help him and each other. Warner was the only survivor. The family members of the children watched in horror; none of them knew how to swim.

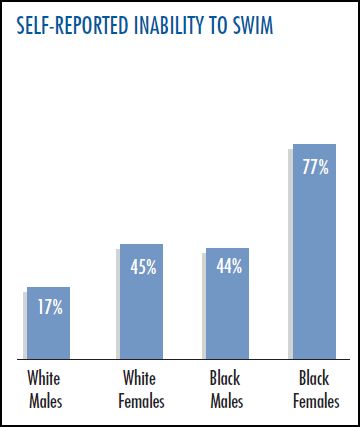

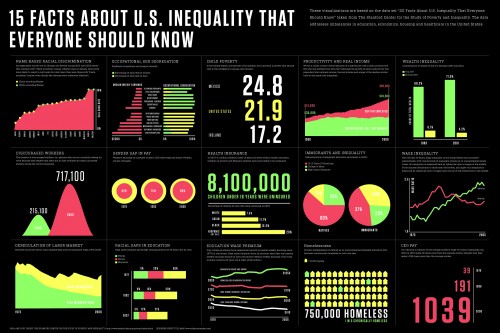

This draws attention to a rarely discussed and deadly disparity between blacks and whites. Black people, especially black women, are much less likely than white people to know how to swim. And, among children, 70% have no or low ability to swim. The figure below, from the International Swimming Hall of Fame, shows that 77% of black women and 44% of black men say that they don’t know how to swim. White women are as likely as black men, but much less likely than black women to report that they can’t swim. White men are the most confident in their swimming ability.

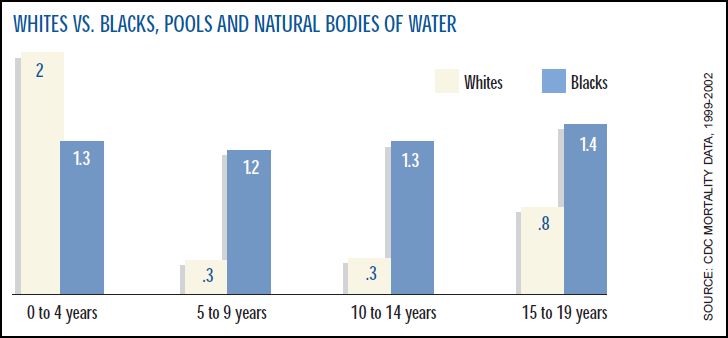

This translates into real tragedy. Black people are significantly more likely to die from drowning than white people (number of drownings out of 100,000):

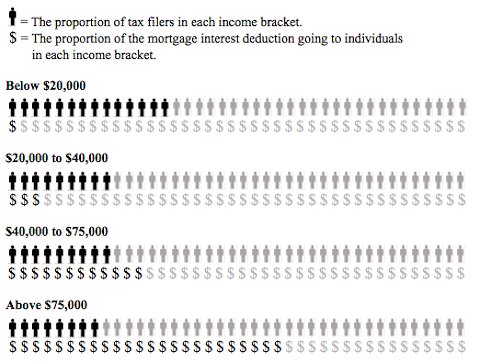

Why are black people less likely to learn to swim than whites? Dr. Caroline Heldman, at FemmePolitical, argues that learning to swim is a class privilege. To learn to swim, it is helpful to have access to a swimming pool. Because a disproportionate number of blacks are working class or poor means that they don’t have backyard swimming pools; while residential segregation and economic disinvestment in poor and minority neighborhoods means that many black children don’t have access to community swimming pools. Or, if they do, they sometimes face racism when they try to access them.

Even if all of these things are in place, however, learning to swim is facilitated by lessons. If parents don’t know how to swim, they can’t teach their kids. And if they don’t have the money to pay someone else, their kids may not learn.

I wonder, too, if the disparity between black women and men is due, in part, to the stigma of “black hair.” Because we have racist standards of beauty, some women invest significant amounts of time and money on their hair in an effort to make it straight or wavy and long. Getting their hair wet often means undoing this effort. Then again, there is a gap between white men and white women too, so perhaps there is a more complicated gender story here.

These are my initial guesses at explaining the disparities. Your thoughts?

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.