Cross-posted at Jezebel.

Most of us are clear on the idea that patriarchies are defined by sexism: the valuing of men over women. In our American patriarchy, however, this is matched and perhaps even superseded by something called androcentrism: the valuing of all-things-masculine over all-things-feminine. We know we live in an androcentric society because masculinized things (playing sports, being a doctor, being self-sufficient) are imagined to be good for everyone (we encourage both our sons and daughters to do these things), but feminized things (playing with dolls, being a nurse, and staying at home to raise children) are considered to be good only for women.

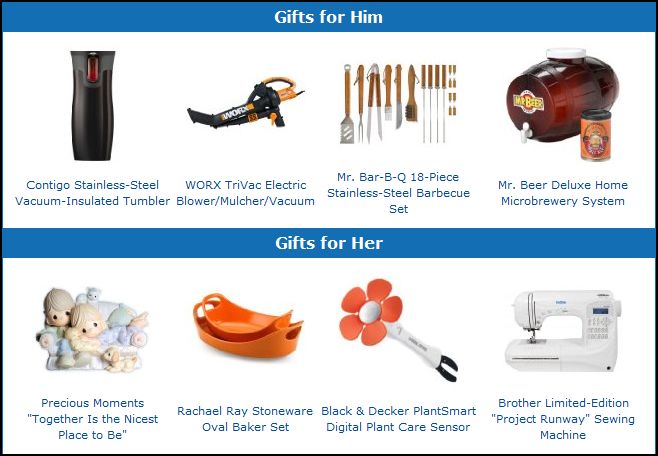

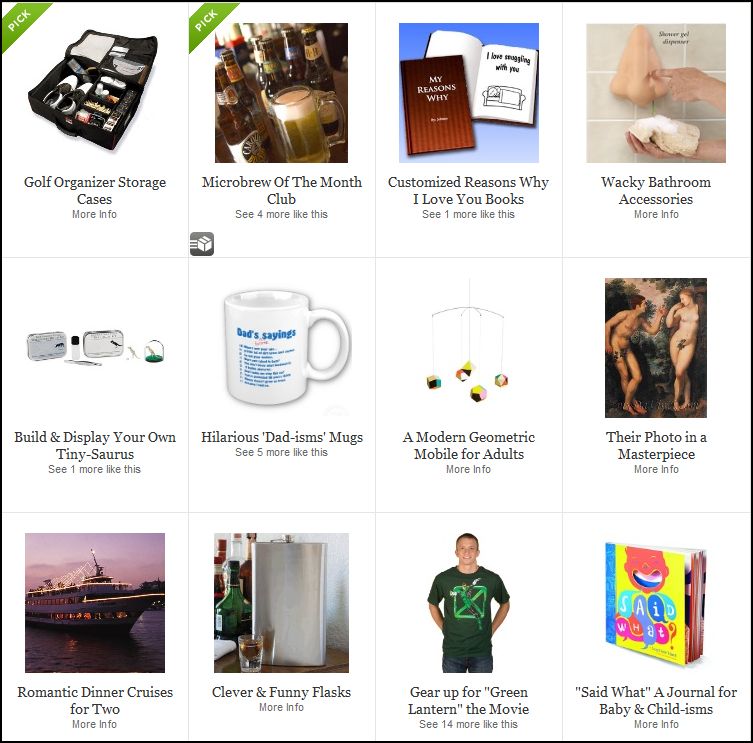

This means that men are teased and ostracized for doing feminized things, as we have demonstrated in advertising for McCoy Crisps, Hungry Man, Solo, Chevy, dog food, Miller beer, beef jerky, cell phones, Dockers, the VW Beetle, and alcohol (see here, here, here and here).

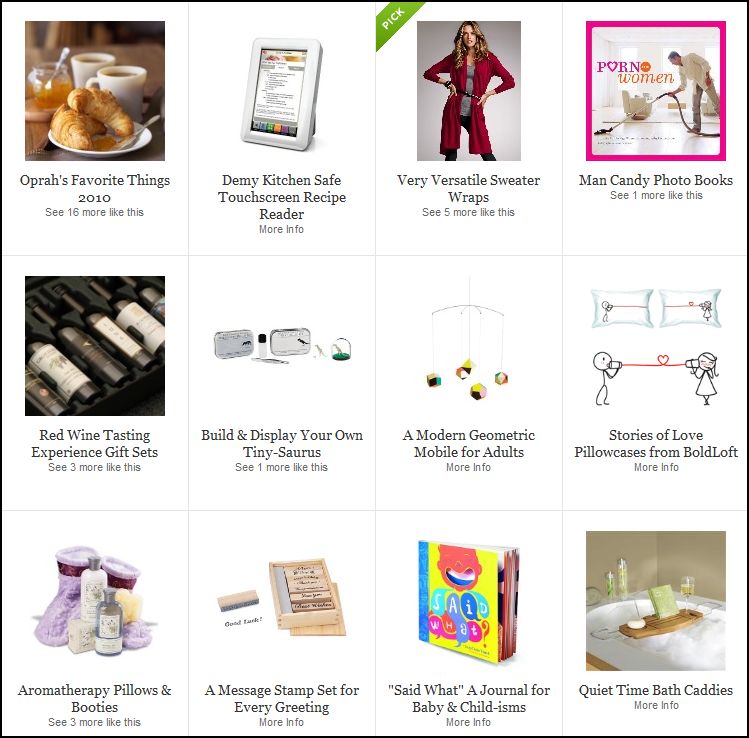

This tendency towards androcentrism means, also, that companies can count on both women and men buying masculinized products, but only women buying feminized products. It’s smart business, then, to masculinize everything. In a New York Times article, for example, Patton reports that Mercedes masculinized its SLK in response to a finding that “too many” women were buying it, something that threatened to feminize the car:

Mercedes says that 52 percent of the registered owners of first-generation SLK’s are women and 48 percent are men; the company would prefer the figures to be more on the order of 60 percent men and 40 percent women…

The standard thinking in the industry is that lots of women will buy a car that appeals to men, but many men — certainly those who wish to avoid the girlie-men label — won’t buy one associated with women.

This logic helps explain the, admittedly tongue-in-cheek (I think), hyper-masculinization of the Honda Odyssey in this commercial, sent in by Nancy N. She writes:

The choice of the black car, the music, and lighting all direct the viewer to think, “this isn’t just a mini-van, this is a man-van, and you aren’t a pansy if you buy it.” …[It is] “technology packed “… with distinctly harder edges. Overall, Honda is trying very hard to override the notion of a “mom car” to sell to a broader audience.

See also: “how to give the perfect man hug” and “how I sit on the bus”. And for more examples of androcentrism, see our posts on the phenomenon in sports (see here and here), cartoons, schools (see here and here), and Cosmo.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.