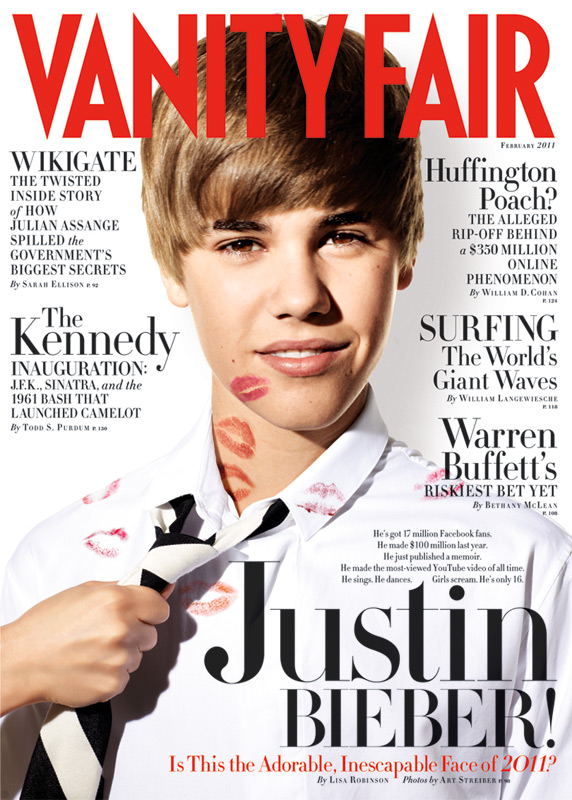

Kari B. sent in an example of the sexualization of teen boys, found at Evil Slutopia. Justin Bieber appears on the cover of the February 2011 Vanity Fair covered in lipstick, with a hand grabbing him by his necktie:

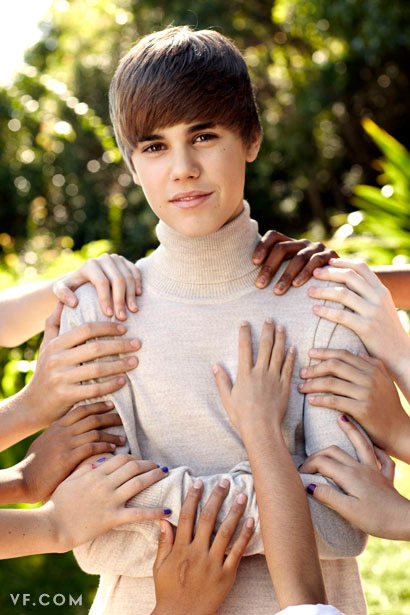

An image from the article:

Justin Bieber is 16 years old — just a year older than Miley Cyrus was when there was a scandal about her photoshoot for Vanity Fair, such that it appeared to potentially threaten her career at Disney by ruining her safe, clean-cut image. I think it’s safe to say that if Miley Cyrus, or another female teen star, posed in photos that showed evidence of being kissed or grabbed by male fans, people would be up in arms about the sexualization of girls. But as we often see, there’s a double-standard, based on the idea that boys are naturally sexual at earlier ages and that boys are sexually invincible. While we might see a teen girl surrounded by men as being in danger, we don’t think of girls as being sexually threatening to boys, or of male teen celebrities’ sexuality being as open to exploitation by publicists, photographers, or other members of the media. And thus, these types of images of Justin Bieber don’t lead to the same outcry as similar images of female teen stars, and don’t cause concern that his career as a teen idol is over.

We’ve discussed the adultification of Justin Bieber before, here and here; you might also check out our post on the sexualization of Jaden Smith.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.