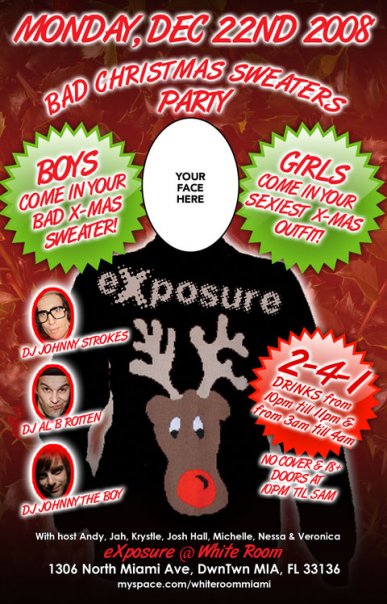

Arielle S. sent in an image of an ad for a Christmas party two years ago at a nightclub in Miami. The ad says it’s a “bad Christmas sweaters party,” but as it turns out, that’s only if you’re a guy. For ladies, it’s apparently a sexy outfit party:

Because even at a party expressly about looking silly in ugly clothes, women aren’t allowed to not be sexy.

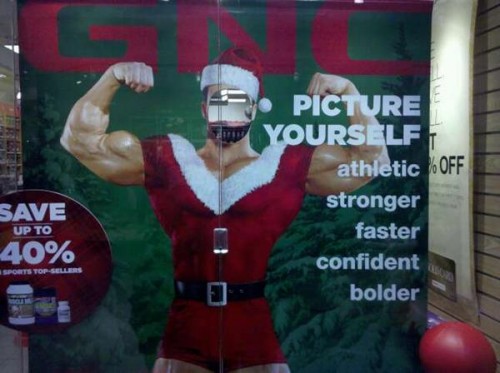

Similarly, Save S. saw these ads for GNC at the mall that make it clear what characteristics men and women are supposed to aspire to have:

So apparently men aren’t worried about being sexy. And women want to look…radiant? I’m not sure what product at GNC would make you radiant, but I can’t imagine it’s good for you.