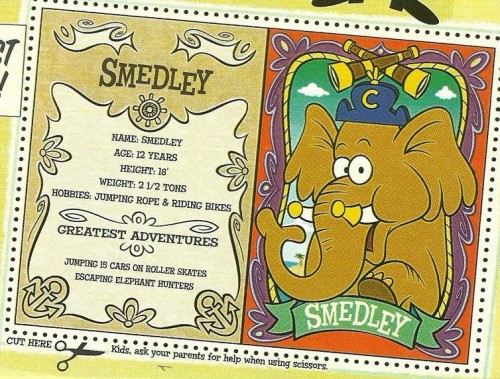

Mab R. sent in a nice example of how children are socialized into gendered expectations. Chunky Monkey Mind has a post about the cut-out trading cards that appeared on the back of Cap’n Crunch cereal boxes a while back. Each card features a Cap’n Crunch character. Here’s the card for Smedley:

Ok, so for the male character we get basic stats, and he’s clearly an active guy who has thrilling adventures.

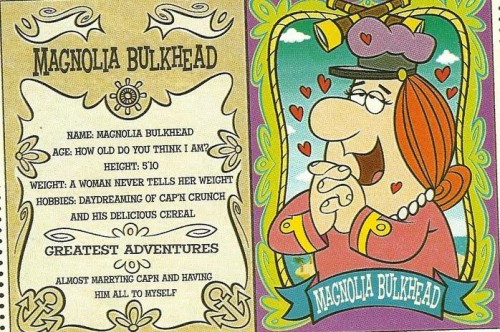

On the same box that featured the Smedley card was a card for Magnolia Bulkhead, who is shown with hearts hovering around her face as she clasps her hands together in rapture:

But of course, being female, she isn’t going to give us all of her vital statistics — in particular, age and weight are secrets women should guard carefully. Also notice the reinforcement of the idea that women are obsessed with romance. While Smedley’s hobbies involve action, Magnolia’s only listed hobby is daydreaming about a man (and his cereal). And her greatest adventure? Why, almost getting married, of course. Yes, the most amazing adventure of her life is something she failed at, but since it held out at least the possibility of romance, and she’s female, it was still the highlight of her life.

Ah, gender stereotypes! Fun for kids of all ages!