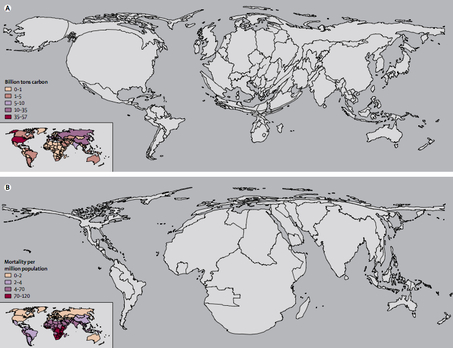

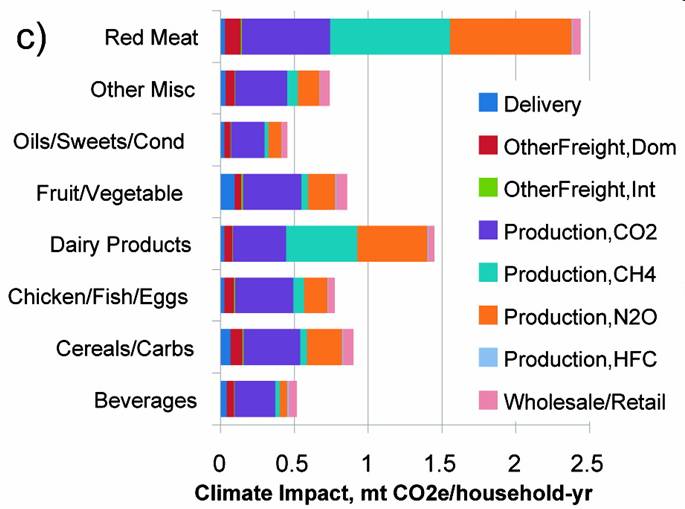

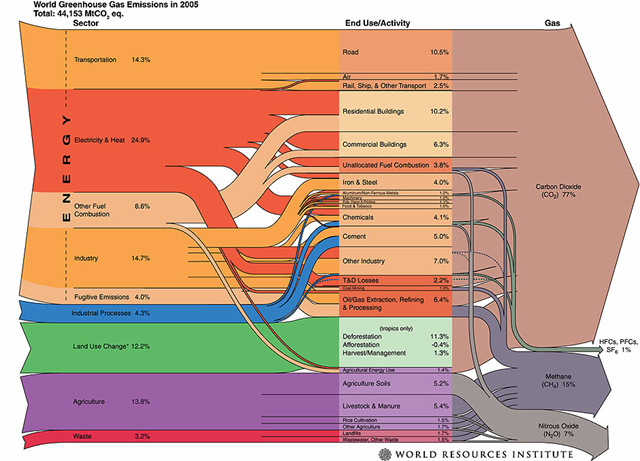

The graphic below is interesting to me in light of the discourse about greenhouse gas emissions. We often hear about emissions from cars and sometimes about emissions from industry. I was surprised, then, to see that electricity and heat was such a large contributor to carbon dioxide emissions. And I feel like land use change and agriculture hardly get discussed at all.

Graphic borrowed from ChartPorn, which also has an interactive graphic that breaks down emissions by country (via Simoleon Sense).

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.