Katrin sent along links to visual portrayals of how much money goes, or could go, to various causes. While sometimes it’s hard to comprehend what a billion, or 300 billion, dollars amounts to, these images give us perspective on just where our priorities lie. The segments below are clipped from the visuals for the U.K. and the U.S. at Information is Beautiful.

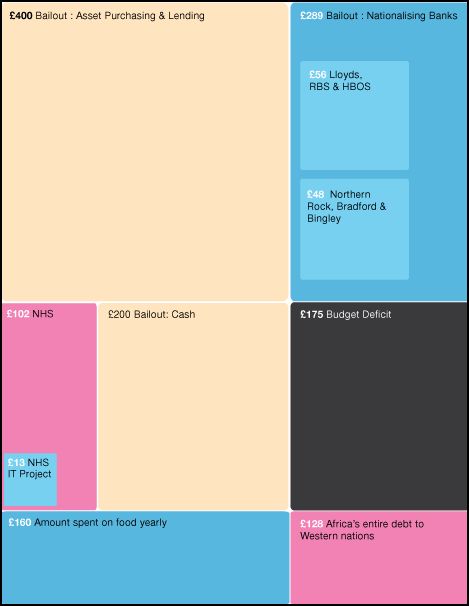

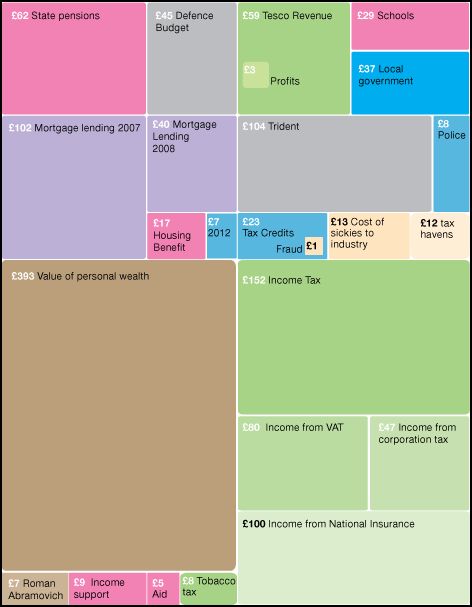

The British example nicely illustrates how little social services like education, police, and welfare cost in the big scheme of things.

It also reveals how easy it would be to wave all of the African countries’ debt to Western countries. Just £128 spread out over the West. Shoot, that’s the money for just a couple of corporate bailouts.

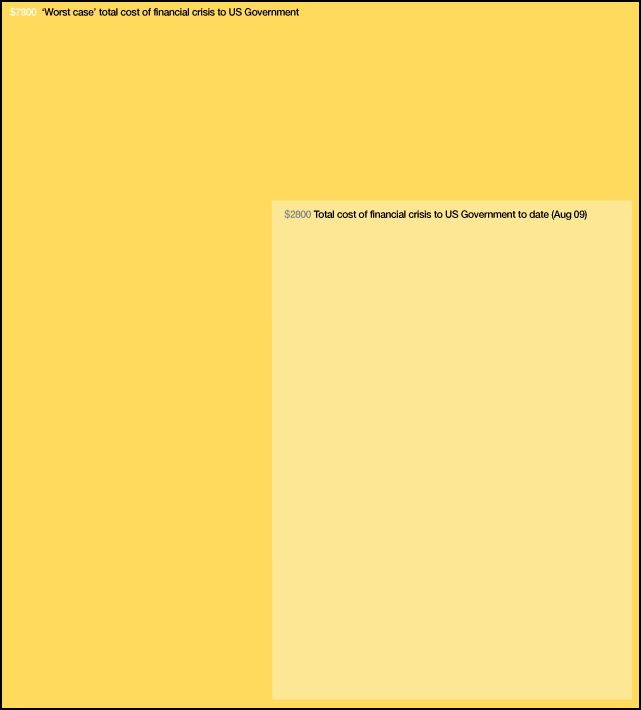

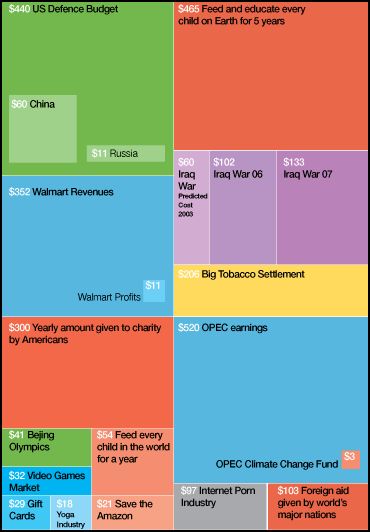

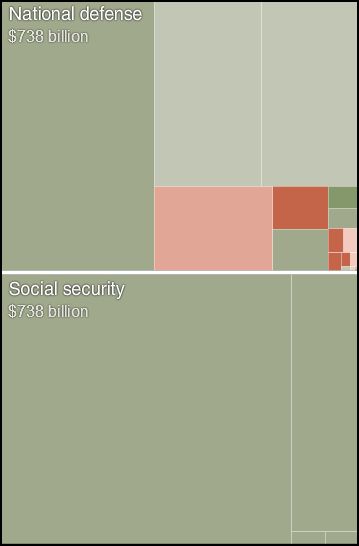

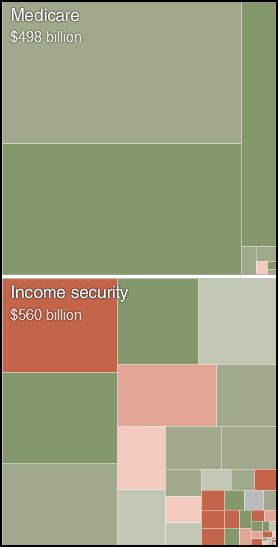

The U.S. example reveals how costly (just) the Iraq war has been. All of our spending pales in comparison to that expenditure., with the exception of what we have spent bailing out the U.S. economy.

It also reveals that the U.S.’s regular defense budget is almot enough to feed and educate every child on earth for five years, and/or about the same as the revenues of Walmart and Nintendo combined.

If we diverted the money spent on porn, we could save the Amazon… almost five times over. For that matter, if we gave our yoga money to the Amazon, that would just about do it.

Bill Gates could have paid for the Beijing Olympics and had money left over.

Dmitriy T.M. sent in an interactive breakdown of the US Budget for 2011. In the figures below, the sizes of the squares represent the proportion of the budget, but the colors refer to changes from 2010 (dark and light pink = less funding, dark and light green = more). These figures will give you an idea, but the graphic is interactive and there’s lots more to learn at the site.

See also our posts on how many starving children could be fed by celebrity’s engagement rings and where U.S. tax dollars go.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.