Judy Z. H. sent in Kanye’s video for Love Lockdown for analysis. My first thought was: they should have just went with Qwest Crew. But I digress.

The video contrasts Kanye, singing in a nearly empty apartment, with tribal imagery.

Here’s my thoughts: The song is about a man who loves a woman but knows intellectually that the relationship is wrong. So he has to leave her, even as his heart breaks to do it. So the song is about a conflict between his heart and his mind or, alternatively, passion and rationality.

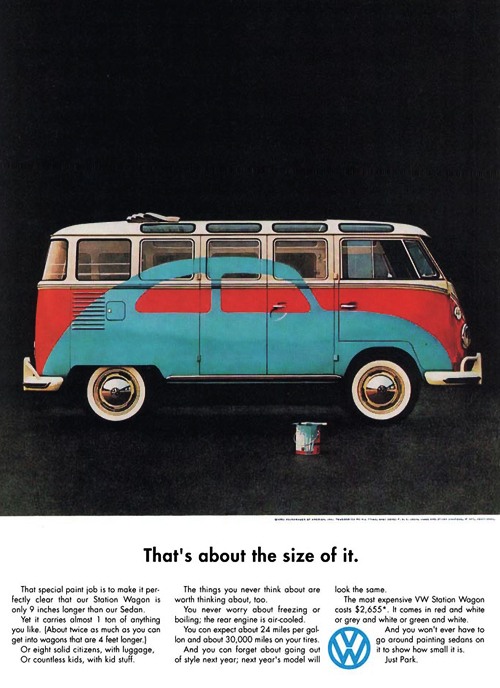

The passion/rationality binary is often layered onto a primitive/modern binary. Primitives, we presume, are superstitious, driven by passions, more instinctual than intellectual, more closely connected to animals and nature more generally. Moderns, by contrast, are assumed to be rational, in control of our emotions; modernity has brought us science and technology and taken us farther away from nature.

Accordingly, the primitives in the video express strong emotions and are dressed in skins and feathers, decorated with the earth, while Kanye calmly sings about a heart-wrenching decision, surrounded by a clean, white, even sterile, apartment, and lounging in the kitchen (the most technological room in the house); the only item other than furniture that we see is a telescope. A telescope! How very modern.

The video works because Kanye’s audience recognizes the modern/primitive binary and all that it implies. But, of course, it’s false. Psychological research (and, as far as I can tell, all of the research on voting behavior) demonstrates again and again that rationality is not our strong point as a species. If anything, what is modern is the inferring of rationality (hello rational choice theorists!), something that we see clearly in this video.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.