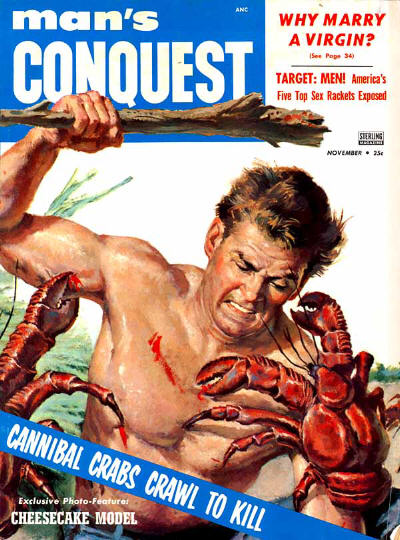

Dmitriy T.M. and Andrew L. sent a link to a collection of post-World War I men’s magazine covers. They are a window into a time when being a man was clearly a very distinct achievement, but much less related to consumption than it is today.

Today’s men’s magazines emphasize control over oneself and the conquest of women, as do these vintage magazines, but instead of tests of strength, cunning, and fighting ability, they emphasize conquest through consumption. The message is to consume the right exercise, the right products (usually hygiene or tech-related), the right advice on picking up women and, well, the right women. In contrast, these old magazines pit man against nature or other men; consumption has not yet colonized the idea of masculinity.

View a selection of the covers at The Art of Manliness.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.