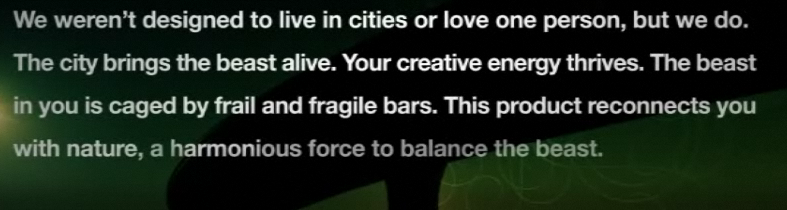

Crazy Vet offers us this rather amazing commercial for BP as an example of “green-washing” or an effort to make a company appear environmentally friendly:

Crazy Vet offers us this rather amazing commercial for BP as an example of “green-washing” or an effort to make a company appear environmentally friendly:

What I think is especially remarkable about this example is how entirely free of any content it manages to be. The commercial combines pretty colors, animation, babies, cute music, and whistling gas pumps. That alone, apparently, is effective in convincing us that BP is environmentally benign. It is pure emotion, completely devoid of an argument.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.