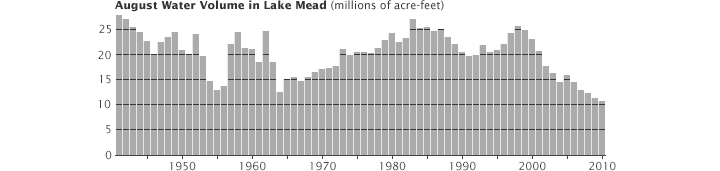

Lake Mead (1958):

Lake Mead (2010):

Via the Earth Observatory.

These two starkly different and somewhat frightening images don’t represent a linear diminishment of Lake Mead. Instead, they are two extremes on a naturally fluctuating water level:

This fluctuating water level isn’t, further, a natural problem. It has, however, become an increasingly social problem. It provides water for the Southwest, a portion of the country that has become thirstier and thirstier. From Maggie Koerth-Baker at BoingBoing:

Take, for instance, Las Vegas, which gets 90 percent of its water from Lake Mead. Back in the 1940s, fewer than 9,000 people lived there. In 2006, the population was estimated at more than 550,000, and growing. Rapidly.

This makes large numbers of people vulnerable to these natural fluctuations in ways that they never were before and potentially creates human disasters out of our own poor planning and resource management. If climate change exacerbates this problem, and it very well might, then the reliability of our water supply is even more fragile.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.