Cross-posted at Reports from the Economic Front.

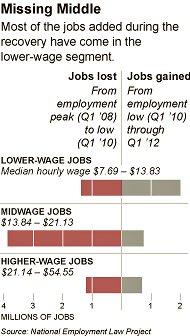

Politicians always seem to be talking about the middle class. They need some new focus groups. According to the Pew Research Center, over the past four years the percentage of adult Americans that say they are in the lower class has risen significantly, from a quarter to almost one-third (see chart below).

Pew also found that the demographic profile of the self-defined lower class has also changed. Young people, according to Pew, “are disproportionately swelling the ranks of the self-defined lower classes.” More specifically some 40% of those between 18 to 29 years of age now identify as being in the lower classs compared to only 25% in 2008.

Strikingly, the percentage of whites and blacks that see themselves in the lower class is now basically equal. The percentage of whites who consider themselves in the lower class rose from less than a quarter in 2008 to 31% in 2012. This brought them in line with blacks, whose percentage remained at a third. The percentage of Latinos describing themselves as lower class rose to 40%, a ten percentage point increase from 2008.

And not surprisingly, as the chart below shows, many who self-identify as being in the lower class are experiencing great hardships. In fact, 1 in 3 faced four or all five of the problems addressed in the survey.

In short, there is a lot of hurting in our economy.