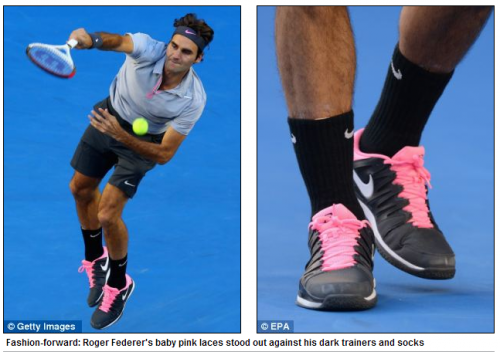

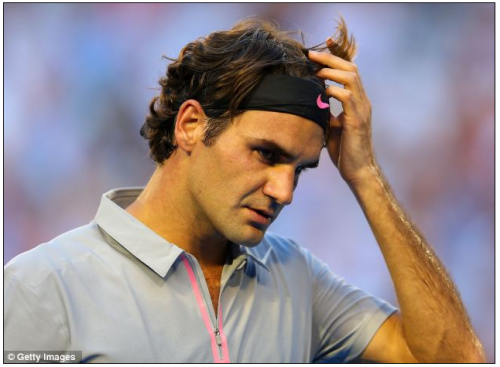

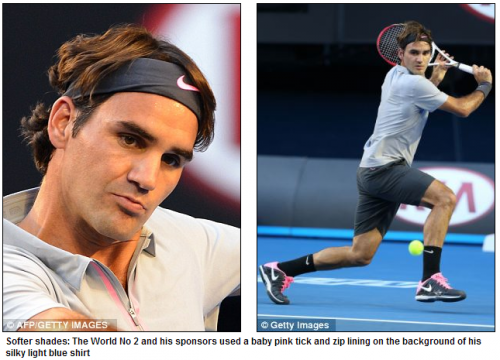

I know, I know. We can expect nothing more from the Daily Mail. And yet I can’t help but point out this scintillating article on what tennis player Roger Federer wore at the Australian Open. An article on what a man was wearing, you might ask? Indeed. What might prompt such an abnormality? Well, you see, Federer was wearing just the slightest bit of pink.

This daring choice earned Federer 374 words in the Mail Online and six photographs highlighting his apparently newsworthy fashion choice.

Now this isn’t a big deal, but it is a particularly striking example of the little ways in which rules around gender are enforced. Federer took a risk by wearing even a little bit of pink; the Daily Mail goes to great lengths to point this out. He also gets away with it, in the sense that the article doesn’t castigate or attempt to humiliate him for doing so.

Federer, however, is near the top of a hierarchy of men. Research shows that men who otherwise embody high-status characteristics — which includes being light-skinned, ostensibly straight, attractive, athletic, and wealthy — can break gender rules with fewer consequences (see also, the fashion choices of Andre 3000 and Kanye). A less high-status man might read this article and take note: Federer can get away with this, kinda, but I should steer clear…. and they’re probably right.

Thanks to Todd Schoepflin @CreateSociology for the tip!

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.