Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Does “the abortion culture” cause infanticide? That is, does legalizing the aborting of a fetus in the womb create a cultural, moral climate where people feel free to kill newborn babies?

It’s not a new argument. I recall a 1998 Peggy Noonan op-ed in the Times, “Abortion’s Children,” arguing that kids who grew up in the abortion culture are “confused and morally dulled.”* Earlier this week, USA Today ran an op-ed by Mark Rienzi repeating this argument in connection with the Gosnell murder conviction.

Rienzi argues that the problem is not one depraved doctor. As the subhead says:

The killers are not who you think. They’re moms.

Worse, he warns, infanticide has skyrocketed.

While murder rates for almost every group in society have plummeted in recent decades, there’s one group where murder rates have doubled, according to CDC and National Center for Health Statistics data — babies less than a year old.

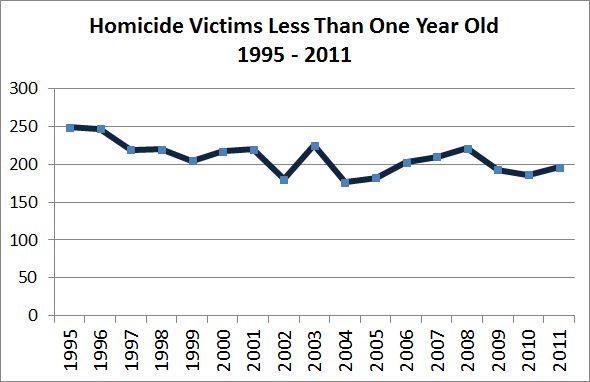

Really? The FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports has a different picture.

Many of these victims were not newborns, and Rienzi is talking about day-of-birth homicides — the type killing Dr. Gosnell was convicted of, a substitute for abortion. Most of these, as Rienzi says are committed not by doctors but by mothers. I make the assumption that the method in most of these cases is smothering. These deaths show an even steeper decline since 1998.

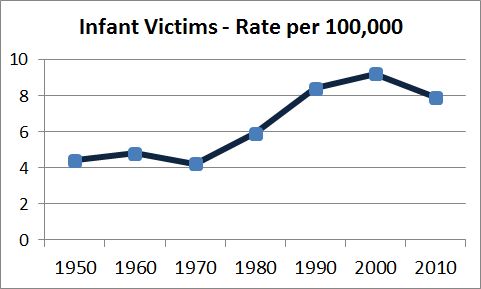

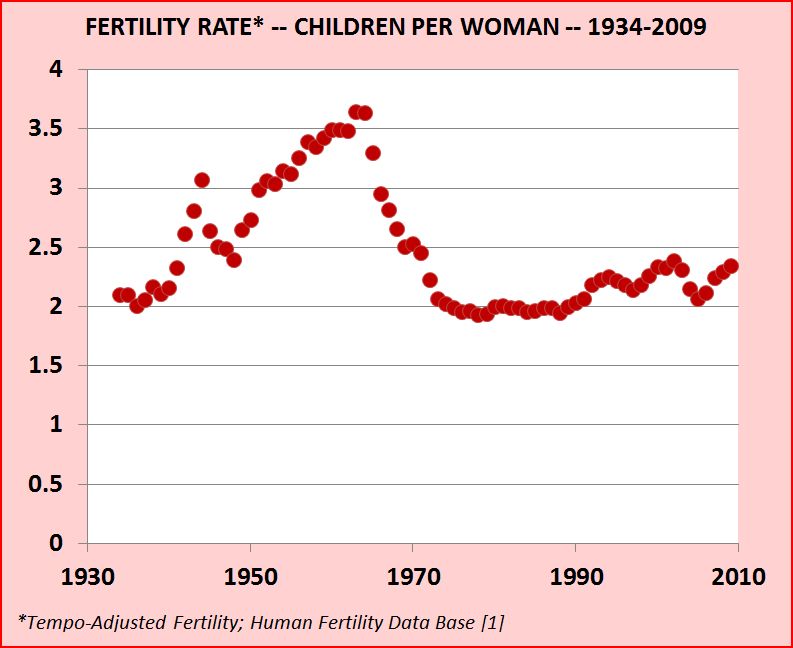

Where did Rienzi get his data that rates had doubled? By going back to 1950.

The data on infanticide fit with his idea that legalizing abortion increased rates of infanticide. The rate rises after Roe v. Wade (1973) and continues upward till 2000.

But that hardly settles the issue. Yes, as Rienzi says, “The law can be a potent moral teacher.” But many other factors could have been affecting the increase in infanticide, factors much closer to actual event — the mother’s age, education, economic and family circumstances, blood lead levels, etc.

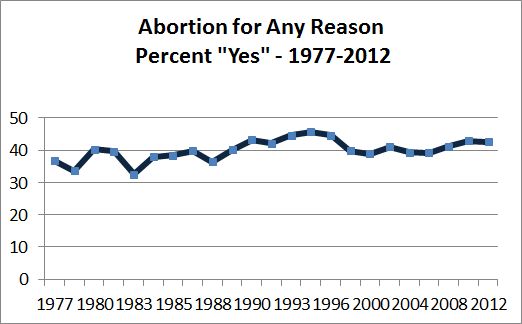

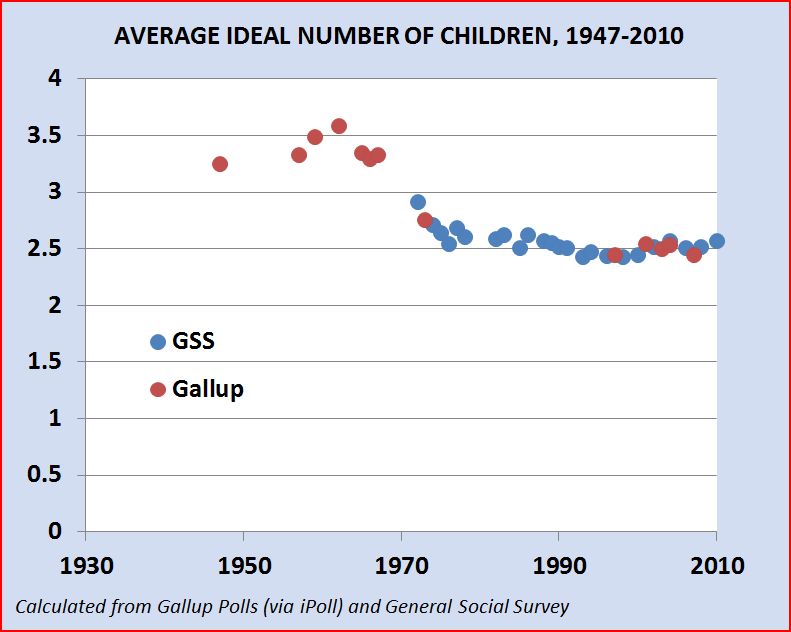

If Roe changed the culture, then that change should be reflected not just in the very small number of infanticides but in attitudes in the general population. Unfortunately, the GSS did not ask about abortion till 1977, but since that year, attitudes on abortion have changed very little. Nor does this measure of “abortion culture” have any relation to rates of infanticide.

Moreover, if there is a relation between infanticide and general attitudes about abortion, then we would expect to see higher rates of infanticide in areas where attitudes on abortion are more tolerant.

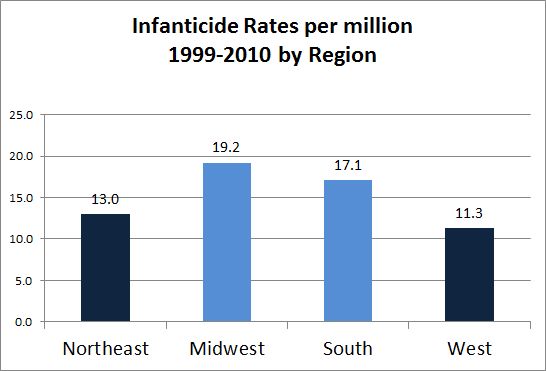

The South and Midwest are most strongly anti-abortion, the West Coast and Northeast the most liberal. So, do these cultural difference affect rates of infanticide?

Well, yes, but it turns out the actual rates of infanticide are precisely the opposite of what the cultural explanation would predict. The data instead support a different explanation of infanticide: Some state laws make it harder for a woman to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. Under those conditions, more women will resort to infanticide. By contrast, where abortion is safe, legal, and available, women will terminate unwanted pregnancies well before parturition.

The absolutist pro-lifers will dismiss the data by insisting that there is really no difference between abortion and infanticide and that infanticide is just a very late-term abortion. As Rienzi puts it:

As a society, we could agree that there really is little difference between killing a being inside and outside the womb.

In fact, very few Americans agree with this proposition. Instead, they do distinguish between a cluster of a few fertilized cells and a newborn baby. I know of no polls that ask about infanticide, but I would guess that a large majority would say that it is wrong under all circumstances. But only perhaps 20% of the population thinks that abortion is wrong under all circumstances.

Whether the acceptance of abortion in a society makes people “confused and morally dulled” depends on how you define and measure those concepts. But the data do strongly suggest that whatever “the abortion culture” might be, it lowers the rate of infanticide rather than increasing it.

* I had trouble finding Noonan’s op-ed at the Times Website. Fortunately, then-Rep. Talent (R-MO) entered it into the Congressional Record.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.