A new report by the ACLU reveals that “debtors’ prisons” in Ohio. The phrase refers to the practice of imprisoning someone for the failure to pay fines. This practice is in violation of the U.S. Constitution. Still, people who can’t afford to pay fines issued in response to traffic violations or misdemeanors are being routinely imprisoned in at least 7 out of 11 counties studied.

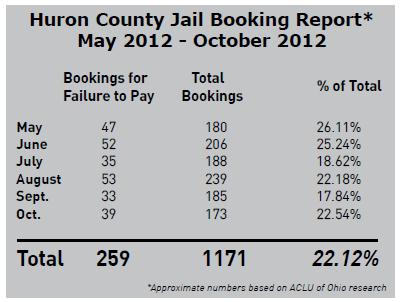

Among the worst offenders is Huron County. An investigation found that as many as 22% of the bookings in Huron were for failure to pay a fine, usually coded as “contempt.” Typically this resulted in a 10 day incarceration. The state would then charge them fees related to being jailed, making it even more unlikely that a person would be able to pay.

The ACLU profiles several individuals. One is a young man named John with a girlfriend and a nine-month-old daughter. He was busted for disorderly conduct and underage consumption of alcohol, plus a few other related charges, and fined $1,300. He agreed to a monthly payment plan to pay off the fines, but wasn’t able to make the payment every month. Norwalk County, in response, put him in jail for 10 days.

He came out of jail owing more and the cycle continued. At the time of the interview, John had been incarcerated for a total of 41 days and had incurred an extra $1,599.10 in fees related to his incarceration. He had paid off $525 of the original $1,300, but owed an additional $2,374.

The ACLU points out that this is obviously an impossible cycle. A person who is struggling financially may lose their job if they are incarcerated for ten days, especially if it happens more than once. Meanwhile, loading on additional fines virtually ensures that they won’t be able to pay. Moreover, however, they point out that it’s not good for Ohio. The costs debtors incur don’t pay for their incarceration, so the state loses money each time they do this. The net loss for the state in John’s case, for example, was $3,853.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.