For the last week of December, we’re re-posting some of our favorite posts from 2012. Cross-posted at Pacific Standard and Global Policy TV.

The United States is unusual among developed countries in guaranteeing exactly zero weeks of paid time-off from work upon the birth or adoption of a child. Japan offers 14 weeks of paid job-protected leave, the U.K. offers 18, Denmark 28, Norway 52, and Sweden offers 68 (yes, that’s over a year of paid time-off to take care of a new child).

The U.S. does guarantee that new parents receive 12 weeks of non-paid leave, but only for parents who work in companies that employ 50 workers or more and who have worked there at least 12 months and accrued 1,250 hours or more in that time. These rules translate to about 1/2 of women. The other half are guaranteed nothing.

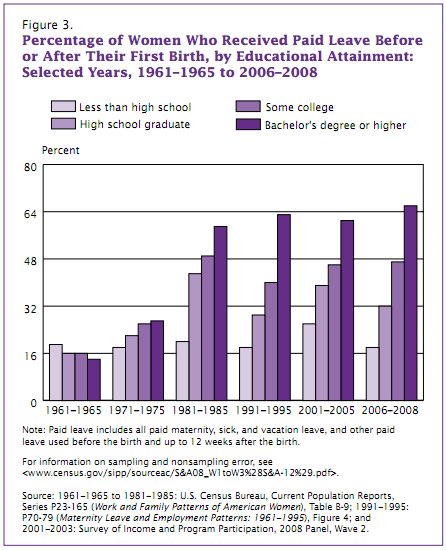

Companies, of course, can offer more lucrative benefits if they choose to, so some parents do get paid leave. This makes the affordability of having children and the pleasure and ease with which one can do so a class privilege. A new report by the U.S. Census Bureau documents this class inequality, using education as a measure. If you look at the latest data on the far right (2006-2008), you’ll see that the chances of receiving paid leave is strongly correlated with level of education:

Looking across the entire graph, however, also reveals that this class inequality only emerged in the early 1970s and has been widening ever since. This is another piece of data revealing the way that the gap between the rich and the poor has been widening.

Just to emphasize how perverse this is:

- People with more education, who on average have higher incomes, are often able to take paid time off; but less-economically advantaged parents are more likely to have to take that time unpaid. During the post-birth period, then, the economic gap widens.

There’s more:

- Many less-advantaged parents can’t afford to take time off un-paid, so they keep working. But even this widens the gap because their salary is lower than the salary the richer person continues to receive during their paid time off of work. So the rich get paid more for staying home than the poor get for going to work.

We often use the minimizing word “just” when describing what stay-at-home parents do. “What are you doing these days?” asks an old friend at a class reunion. “Oh, just staying home and taking care of my kids,” a parent might say, as if raising kids is “doing nothing.” We trivialize what parents do. But, in fact, raising children is a valuable contribution to the nation. We need a next generation to keep moving forward as a country. Unfortunately the U.S. continues to treat having kids like a hobby (something its citizens choose to do for fun, and should pay for themselves). Without state support for early parenting, being present in those precious early months is a class-based privilege, one that ultimately exacerbates the very class disadvantage that creates unequal access to the luxury of parenting in the first place.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.