Cross-posted at The Huffington Post.

Why do women wear high heels? Because men did.

Men were the first sex to don the shoe. They were adopted by the European aristocracy of the 1600s as a signal of status. The logic was: only someone who didn’t have to work could possibly go around in such impractical footwear. (Interestingly, this was the same logic that encouraged footbinding in China.)

Women started wearing heels as a way of trying to appropriate masculine power. In the BBC article on the topic, Elizabeth Semmelhack, who curates a shoe museum, explains:

In the 1630s you had women cutting their hair, adding epaulettes to their outfits…

They would smoke pipes, they would wear hats that were very masculine. And this is why women adopted the heel — it was in an effort to masculinise their outfits.

The lower classes also began to wear high heels, as fashions typically filter down from elite.

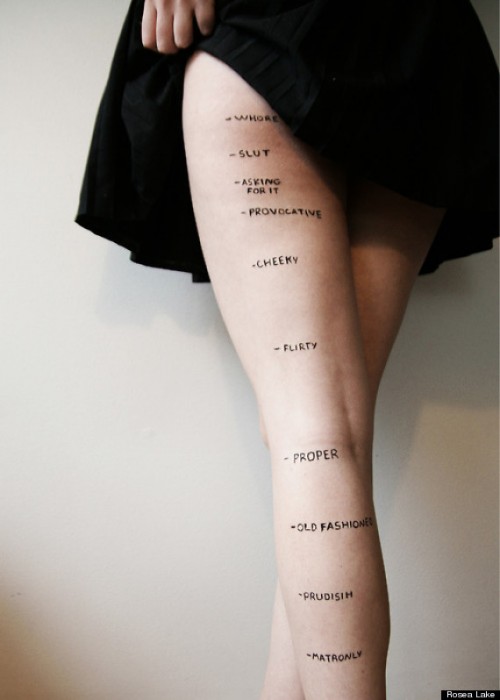

How did the elite respond to imitation from “lesser” people: women and workers? First, the heels worn by the elite became increasingly high in order to maintain upper class distinction. And, second, heels were differentiated into two types: fat and skinny. Fat heels were for men, skinny for women.

This is a beautiful illustration of Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of class distinction. Bourdieu argued that aesthetic choices function as markers of class difference. Accordingly, the elite will take action to present themselves differently than non-elites, choosing different clothing, food, decor, etc. Expensive prices help keep certain things the province of elites, allowing them to signify their power; but imitation is inevitable. Once something no longer effectively differentiates the rich from the rest, the rich will drop it. This, I argue elsewhere, is why some people care about counterfeit purses (because it’s not about the quality, it’s about the distinction).

Eventually men quit wearing heels because their association with women tainted their power as a status symbol for men. (This, by the way, is exactly what happened with cheerleading, originally exclusively for men). With the Enlightenment, which emphasized rationality (i.e., practical footwear), everyone quit wearing high heels.

What brought heels back for women? Pornography. Mid-nineteenth century pornographers began posing female nudes in high heels, and the rest is history.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.