Cross-posted at Racialicious.

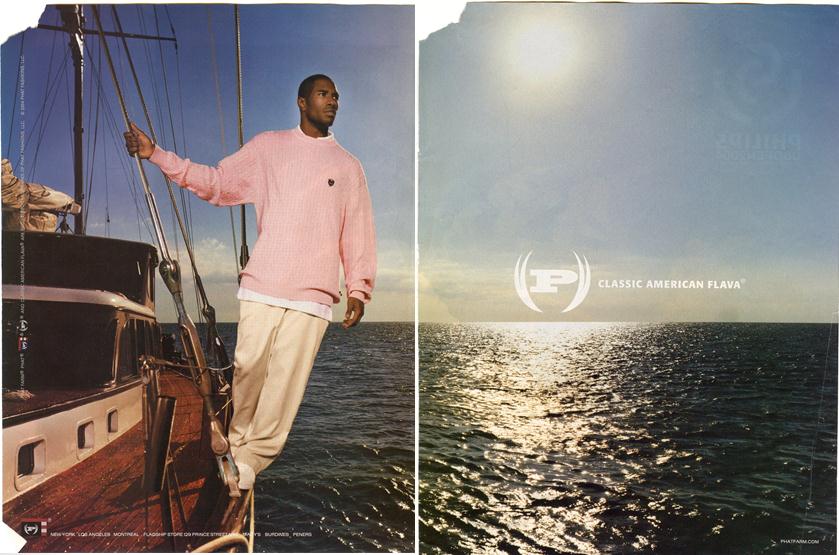

I featured the two-page ad below in one of the first posts I ever wrote for SocImages (it was October of 2007 and we’d written less than 100 posts; today we’re approaching 5,000, but I digress…). It’s still one of my very favorite images.

I use it in Sociology 101 when I argue that race, class, and gender are, among other things, performances. Activities, items, and behaviors carry class, race, and gender meanings. In order to tell stories about ourselves, we strategically combine these things with the meanings we carry on our bodies (a gendered shape, skin color and hair texture etc., and signs of economic wealth or deprivation).

The ad for PhatFarm deftly balances Blackness (the body), upper-class Whiteness (the sailboat), and femininity (the pink sweater). In strategically using culturally-resonant signifiers, he challenges popular representations of the Black body.

This happens in real life too. Journalist Brent Staples powerfully discusses how he adds a signifier of upper-class Whiteness to his large Black body in order to avoid the discomfort of frightening people on the streets of New York.

…I employ what has proved to be an excellent tension-reducing measure: I whistle melodies from Beethoven and Vivaldi and the more popular classical composers. Even steely New Yorkers hunching toward nighttime destinations seem to relax and occasionally they even join in the tune. Virtually everybody seems to sense that a mugger wouldn’t be warbling bright, sunny selections from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.

“It is my equivalent to the cowbell that hikers wear when they know they are in bear country,” Staples adds, referring to the fact that being perceived as dangerous can itself be dangerous, as we know from the example of Trayvon Martin and Rodrigo Diaz, who was shot in the head in January when he accidentally pulled into the wrong driveway thinking it belonged to a friend.

Thinking of class, race, and gender as performances gives us credit for being agents. We don’t have control over what the signifiers are, nor how people read our bodies, but we can actively try to manage those meanings. Of course, some people have to do more “damage control” than others.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.