It always gives an old sociologist like me a big thrill when a classical concept that I love appears in a mainstream cultural product. I received such a buzz when I saw the movie Lee Daniels’ The Butler over the Labor Day weekend.

One of the movie’s African American characters, speaking in the 1940s, notes that a Black man must wear “two faces,” one for other Blacks and another for Whites. Perceptive critics have identified how this borrows from “double consciousness,” a concept that W.E.B. DuBois first wrote about in 1897. A.O. Scott cites Paul Laurence Dunbar’s line, “We wear the mask that grins and lies”; whilst Frank Roberts notes that the movie’s butler “wrestles with the realization that he is in The White House but certainly not of it,” which in turn illustrates the wider dilemma of being in America but not of America.

.

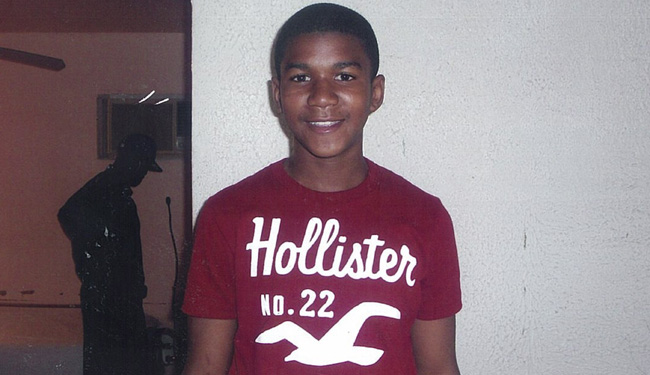

However, what really gives the movie its power is how it resonates with the continuing experiences of African Americans today. Black men who are still shell-shocked by the George Zimmerman verdict will know only too well how they often have to show “two faces” in order to avoid harassment. Barack Obama noted this fact when he observed, a week after the verdict, that there “are very few African American men who haven’t had the experience of walking across the street and hearing the locks click on the doors of cars” or of “getting on an elevator and a woman clutching her purse nervously and holding her breath until she had a chance to get off.”

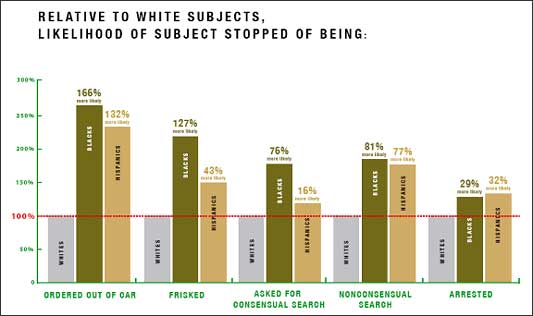

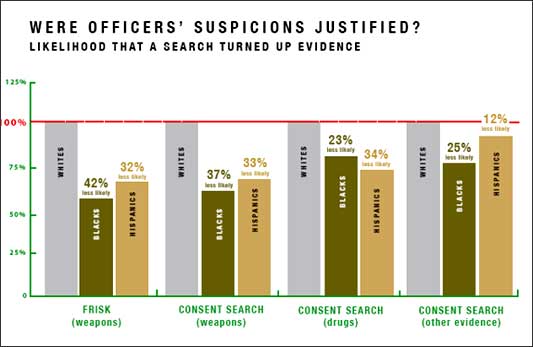

Similarly, Father Bryan Massingale, who is a priest of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee and a professor of theology at Marquette University, records how he was once “abruptly stopped by the police, rudely questioned and roughly searched, under the suspicion that I was the perpetrator of a robbery” and how “Living with such terror and indignity is to be expected” even if you are ” a priest, a university professor, and a respected member of the community (or so I would have thought).” Such profiling strongly resembles DuBois’ emphasis upon:

…this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.

The entire subtext of The Butler is the manner in which the movie’s different characters cope with the task of continually “measuring one’s soul” in this way: the continual feeling of being trapped in the gaze of the white employer’s “contempt and pity.” It is a tribute to the ability of popular culture to occasionally convey powerful truths that this movie does not pull its punches in staying true to that part of DuBois’ sociological vision.

Dr. Jonathan Harrison earned a PhD in Sociology from the University of Leicester, UK. His research interests include the Holocaust, comparative religion, racism, and the history of African Americans in Florida. He teaches at Florida Gulf Coast University and Hodges University. He’d like to thank Dr. Kris De Welde for her comments on earlier drafts of this piece.