If the well-being of our children is an indicator of the health of our society we definitely should be concerned. Almost one-fourth of all children in the U.S. live in poverty.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation publishes an annual data book on the status of American children. Here are a few key quotes from 2014 (all data refer to children 18 and under, unless otherwise specified):

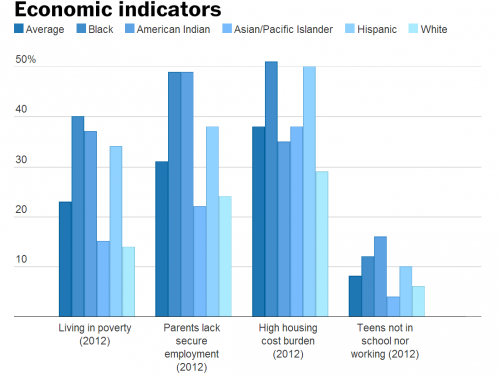

- Nationally, 23 percent of children (16.4 million) lived in poor families in 2012, up from 19 percent in 2005 (13.4 million), representing an increase of 3 million more children in poverty.

- In 2012, three in 10 children (23.1 million) lived in families where no parent had full-time, year-round employment. Since 2008, the number of such children climbed by 2.9 million.

- Across the nation, 38 percent of children (27.8 million) lived in households with a high housing cost burden in 2012, compared with 37 percent in 2005 (27.4 million).

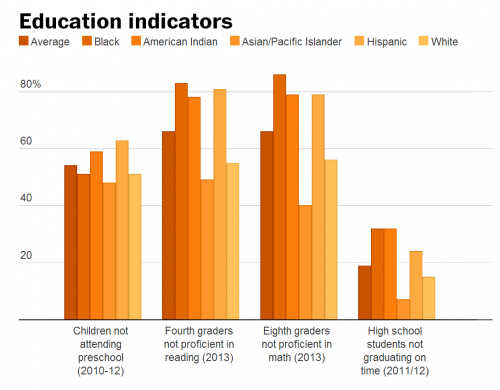

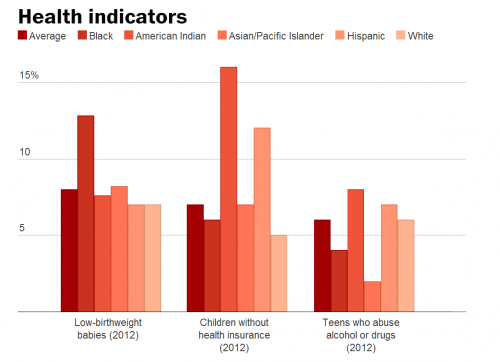

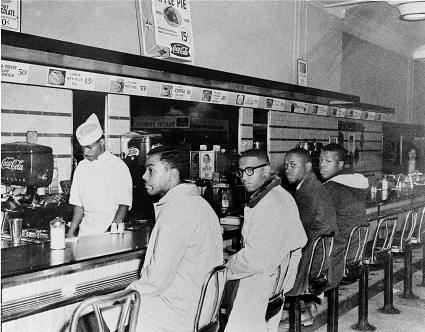

As alarming as these statistics are, they hide the terrible and continuing weight of racism. Emily Badger, writing in the Washington Post, produced the following charts based on tables from the data book.

Children live in poverty because they live in families in poverty. Sadly, despite the fact that we have been in a so-called economic expansion since 2009, most working people continue to struggle. The Los Angeles Times reported that “four out of 10 American households were straining financially five years after the Great Recession — many struggling with tight credit, education debt and retirement issues, according to a new Federal Reserve survey of consumers.”

Martin Hart-Landsberg is a professor of economics at Lewis and Clark College. You can follow him at Reports from the Economic Front.