What would you think of Woody from Toy Story if he wore pink?

Would you think the color choice was incongruous — that it didn’t seem masculine enough for a 1950s-era cowboy toy?

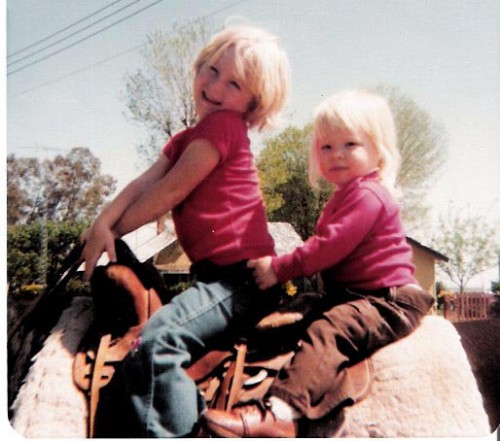

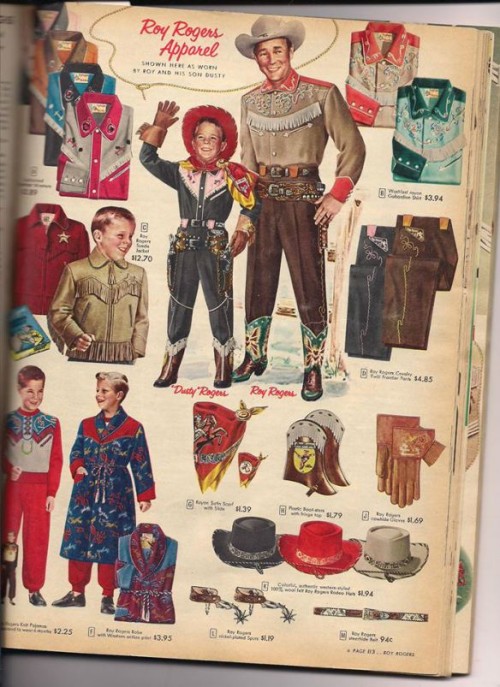

Well, you’d be wrong. Check out these images from the 1955 Sears Christmas Book catalog that Elizabeth Sweet, a newly minted Ph.D. from the University of California at Davis, sent me. Here’s Roy Rogers Apparel, featuring Roy Rogers and his son, Dusty – who is wearing a cowboy outfit with red, yellow, and pink accents:

To modern eyes, this is surprising. “Pink is a girls’ color,” we think. This association has become so firmly entrenched in our cultural imagination that people are flabbergasted to learn that until the 1950s, pink was often considered a strong color and, therefore, was associated with boys.

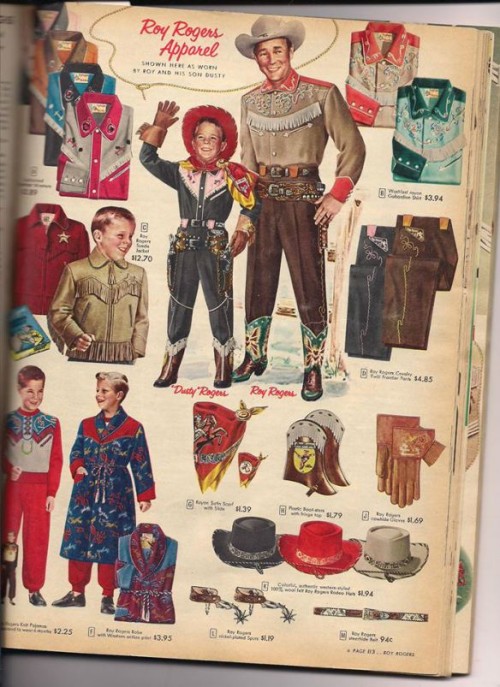

But it wasn’t only for boys. Although gender segregation is de rigeur today, it wasn’t back then. Look at these outfits for boys and girls, also from the 1955 Sears catalog: There are brown and red outfits for boys and girls. Pink and blue outfits for boys and girls. Blue and green outfits for boys and girls.

These spreads make it clear that in the 1950s, when Woody’s Roundup is supposed to have originated, Woody would have been pretty darned stylish in pink.

A decade later, things had started changing; pink was more closely associated with girls. (As Elizabeth notes of the Sears catalogs in her collection, “I didn’t find anything similar in 1965.”)

In today’s marketplace, I believe parents would love to see options like these. In fact, just yesterday, one of my friends posted this to facebook about his failed shopping trip:

Alright, parents, I went to buy my daughter cool costume stuff like pirate stuff and cowgirl stuff and all I found was princess outfits. She doesn’t know the word “princess.” She knows the words ‘cowgirl” and “pirate.” What’s the deal? Why does every company want her to be a princess? Why can’t she be an awesome cowgirl pirate?

Sadly, the reason is that in the retail world, this kind of diversity just doesn’t fly anymore. The status quo is segregation; as Elizabeth Sweet has argued, “finding a toy that is not marketed either explicitly or subtly (through use of color, for example) by gender has become incredibly difficult.” And the more entrenched this practice becomes, the harder it becomes to change, as change is perceived by marketers and retailers as a risk.

Therefore, for the foreseeable future, pink will serve as a clear delineation in the marketplace: If something is pink, it is most definitely not for boys, who regard it as a contagion — something to be avoided at all costs.

So it is that if Woody wore pink today, he would be unintelligible in the marketplace. And so it is that my friend can’t find a good cowgirl outfit for his little girl: he’d have to travel back to 1955 to do so.

The push for “girly” to be synonymous with “pink” saddens me. It has caused girls’ worlds to shrink, and it only reinforces for boys the idea that they should actively avoid anything girlish. Monochromatic girlhood drives a wedge between boys and girls — separating their spheres during a time when cross-sex play is healthy and desirable, and when their imaginations should run free.

Instead, we’re limiting our kids.

Rebecca Hains, PhD is a media studies professor at Salem State University. Follow her on Facebook and Twitter. Read the original post here. Cross-posted at Business Insider and The Christian Science Monitor.