The short answer is, pretty well. But that’s not really the point.

In a previous post I complained about various ways of collapsing data before plotting it. Although this is useful at times, and inevitable to varying degrees, the main danger is the risk of inflating how strong an effect seems. So that’s the point about teen test scores and adult income.

If someone told you that the test scores people get in their late teens were highly correlated with their incomes later in life, you probably wouldn’t be surprised. If I said the correlation was .35, on a scale of 0 to 1, that would seem like a strong relationship. And it is. That’s what I got using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. I compared the Armed Forces Qualifying Test scores, taken in 1999, when the respondents were ages 15-19 with their household income in 2011, when they were 27-31.

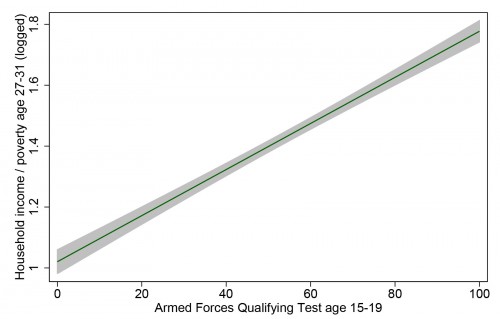

Here is the linear fit between between these two measures, with the 95% confidence interval shaded, showing just how confident we can be in this incredibly strong relationship:

That’s definitely enough for a screaming headline, “How your kids’ test scores tell you whether they will be rich or poor.” And it is a very strong relationship – that correlation of .35 means AFQT explains 12% of the variation in household income.

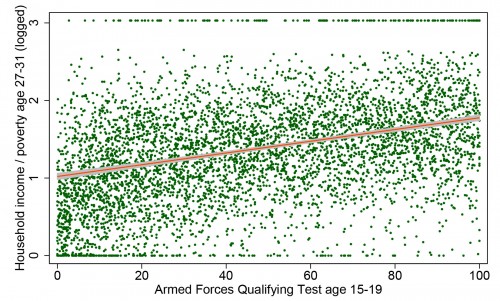

But take heart, ye parents in the age of uncertainty: 12% of the variation leaves a lot left over. This variable can’t account for how creative your children are, how sociable, how attractive, how driven, how entitled, how connected, or how White they may be. To get a sense of all the other things that matter, here is the same data, with the same regression line, but now with all 5,248 individual points plotted as well (which means we have to rescale the y-axis):

Each dot is a person’s life — or two aspects of it, anyway — with the virtually infinite sources of variability that make up the wonder of social existence. All of a sudden that strong relationship doesn’t feel like something you can bank on with any given individual. Yes, there are very few people from the bottom of the test-score distribution who are now in the richest households (those clipped by the survey’s topcode and pegged at 3 on my scale), and hardly anyone from the top of the test-score distribution who is now completely broke.

But I would guess that for most kids a better predictor of future income would be spending an hour interviewing their parents and high school teachers, or spending a day getting to know them as a teenager. But that’s just a guess (and that’s an inefficient way to capture large-scale patterns).

I’m not here to argue about how much various measures matter for future income, or whether there is such a thing as general intelligence, or how heritable it is (my opinion is that a test such as this, at this age, measures what people have learned much more than a disposition toward learning inherent at birth). I just want to give a visual example of how even a very strong relationship in social science usually represents a very messy reality.

Cross-posted at Family Inequality and Pacific Standard.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.