We don’t prohibit all dangerous behavior, or even behavior that endangers others, including people’s own children.

Question: Is the limit of acceptable risks to which we may subject our own children determined by absolute risks or relative risks?

Case for consideration: Home birth.

Let’s say planning to have your birth at home doubles the risk of some serious complications. Does that mean no one should do it, or be allowed to do it? Other policy options: do nothing, discourage home birth, promote it, regulate it, or educate people about the risks and let them do what they want.

Here is the most recent result from a large study reported on the New York Times Well blog, which looks to me like it was done properly, from the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Researchers analyzed about 2 million birth records of live, term (37-43 weeks), singleton, head-first births, including 12,000 planned home births.

The planned-home birth mothers were generally relatively privileged, more likely to be White and non-Hispanic, college-educated, married, and not having their first child. However, they were also more likely to be older than 34 and to have waited to see a doctor until their second trimester.

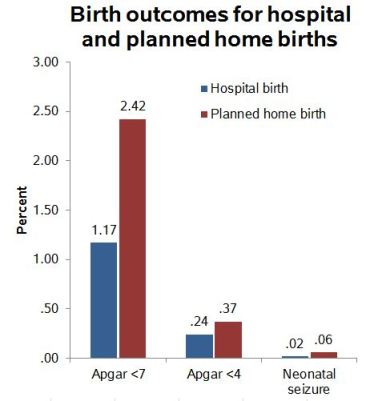

On three measures of birth outcomes, the home-birth infants were more likely to have bad results: low Apgar scores and neonatal seizures. Apgar is the standard for measuring an infant’s wellbeing within 5 minutes of birth, assessing breathing, heart rate, muscle tone, reflex irritability and circulation (blue skin). With up to 2 points on each indicator, the maximum score is 10, but 7 or more is considered normal and under 4 is serious trouble. Low scores are usually caused by some difficulty in the birth process, and babies with low scores usually require medical attention. The score is a good indicator of risk for infant mortality.

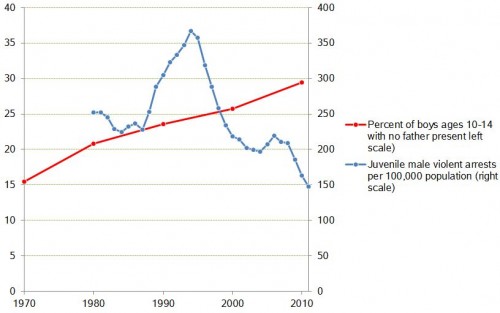

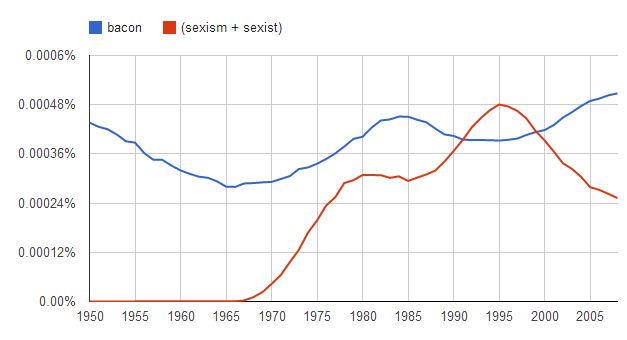

These are the unadjusted rates of middle- and low-Apgar scores and seizure rates:

These are big differences considering the home birth mothers are usually healthier. In the subsequent analysis, the researchers controlled for parity, maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, gestational age at delivery, number of prenatal care visits, cigarette smoking during pregnancy, and medical/obstetric conditions. With those controls, the odds ratios were 1.9 for Apgar<4, 2.4 for Apgar<7, and 3.1 for seizures. Pretty big effects.

These are big differences considering the home birth mothers are usually healthier. In the subsequent analysis, the researchers controlled for parity, maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, gestational age at delivery, number of prenatal care visits, cigarette smoking during pregnancy, and medical/obstetric conditions. With those controls, the odds ratios were 1.9 for Apgar<4, 2.4 for Apgar<7, and 3.1 for seizures. Pretty big effects.

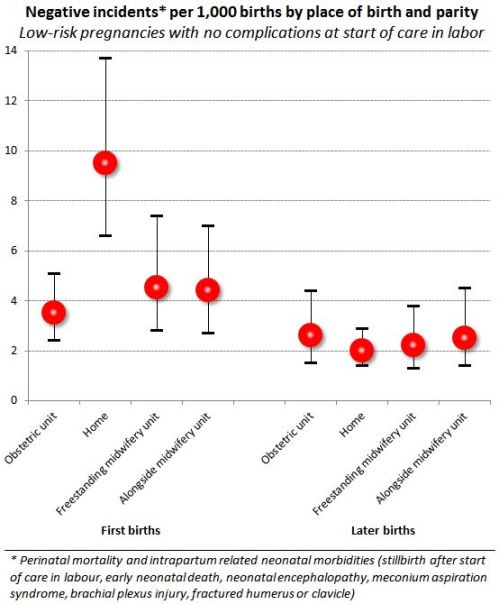

Two years ago I wrote about a British study that found much higher rates of birth complications among home births when the mother was delivering her first child. This is my chart for their findings:

Again, those were the unadjusted rates, but the disparities held with a variety of important controls.

These birth complication rates are low by world historical standards. In New Delhi, India, in the 1980s 10% of 5-minute-olds had Apgar scores of 3 or less. So that’s many-times worse than American home births. On the other hand, a number of big European countries (Germany, France, Italy) have Apgar<7 rates of 1% or less, which is much better.

A large proportional increase on a low risk for a high-consequence event (like nuclear meltdown) can be very serious. A large absolute risk of a common low-consequence event (like having a hangover) can be completely acceptable. Birth complications are somewhere in between. But where?

Seems like a good topic for discussion, and having some real numbers helps. Let me know what you decide.

Cross-posted at Family Inequality.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.