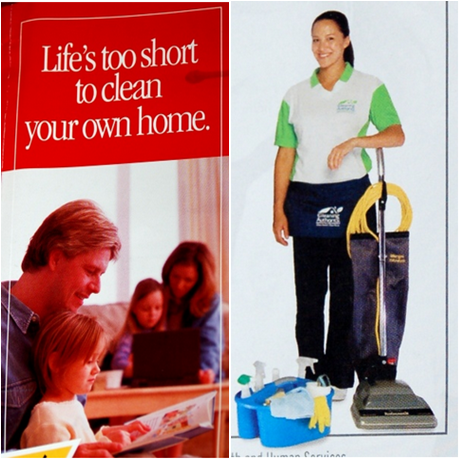

In light of the mean-spirited Obama-wants-everyone-on-food-stamps meme, and the Heritage Foundation’s mocking attack on poor people as air-conditioned, Xbox-loving couch potatoes, let’s consider something else about poor single parents — especially poor mothers: their Google searches.

That’s right, in addition to refrigerators, apparently almost everyone in America today has Internet access — often at their local public libraries.

And yet they still complain about their little problems. They type searches into Google like, “help paying electric bill,” “hair falling out,” and even — presumably so they can laugh at the poor suckers who actually work for a living — “walmart jobs.”

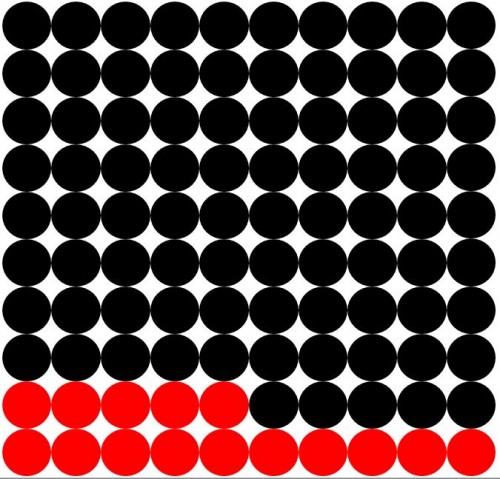

The old “misery index” was just unemployment plus inflation. Maybe the new index to watch is Google searches for “help for single mothers.” Here is the trend for that search, along with one of the searches that most closely follows its trend, “walmart jobs.” The temporal correlation between these two — the amount they rise and fall together over time — is .96 on a scale of 0 to 1.

You can see the full list of 100 searches most correlated with “help for single mothers” by following this link.

You can see the full list of 100 searches most correlated with “help for single mothers” by following this link.

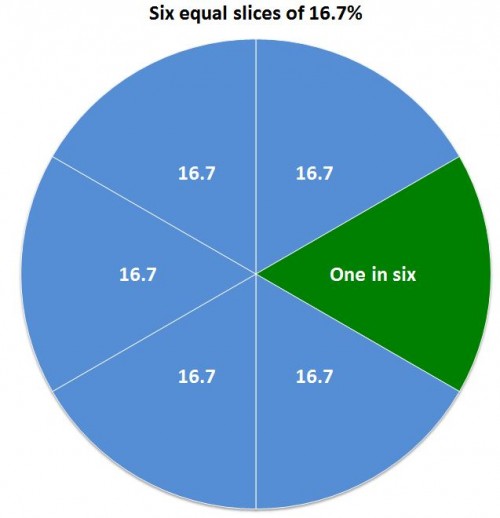

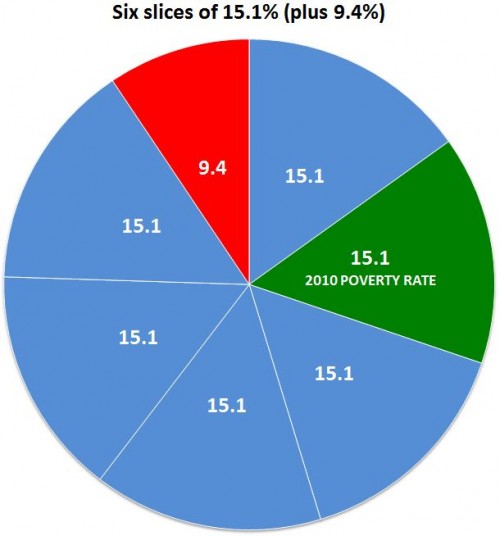

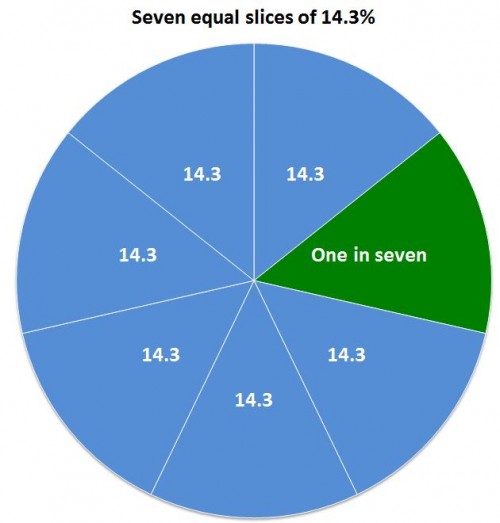

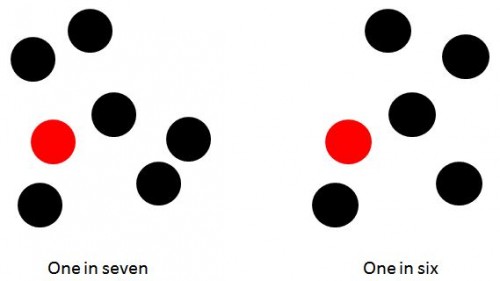

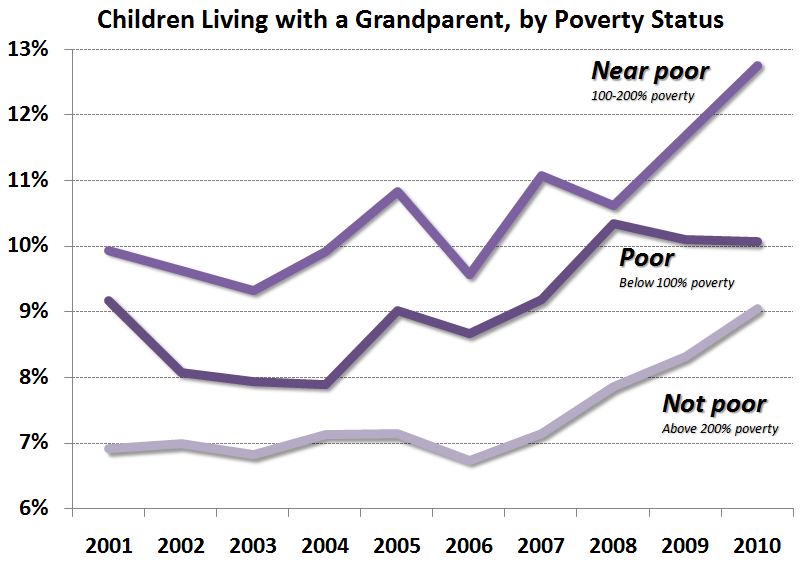

After the poverty report came out last month, comedian Andy Borowitz tweeted, “One in six Americans is living in poverty, but the other five are more concerned about the changes to Facebook.” Whether you’re in the first group or the latter one — or neither — it’s worth pausing for a minute to think about the lives of people Googling things like, “help with rent,” “iud side effects,” “cheap dinner ideas” and “get a credit card with bad credit.” (The searches all correlate with “help for single mothers” at .94 or higher.)

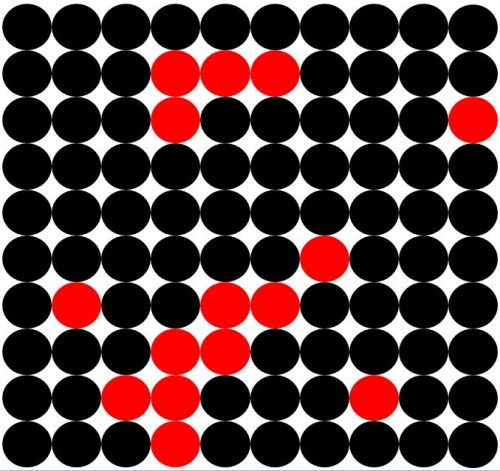

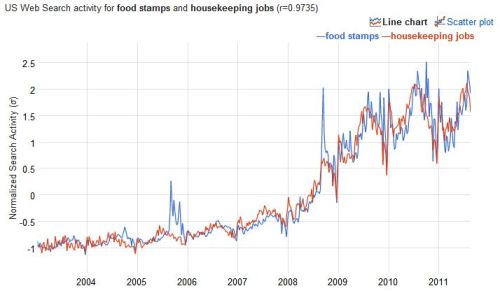

A similar list comes up in the correlations with searches for “food stamps.” Here it is graphed with “housekeeping jobs,” correlated at .97:

The list of correlated searches is similar, including a preponderance of women’s health terms (“clots during period”) economic crises (“light bill”), and ideas for climbing out of an economic hole (“medical assistant jobs,” “dispatcher jobs”).

The list of correlated searches is similar, including a preponderance of women’s health terms (“clots during period”) economic crises (“light bill”), and ideas for climbing out of an economic hole (“medical assistant jobs,” “dispatcher jobs”).

On the plus side, both of these trends peaked in mid-2010, for now. So maybe things have stopped getting worse quite so fast. Or maybe they just lost their Internet access at the library due to budget cuts.

Am I being selective, not reporting the searches like “loving this cool TV,” and “food stamps rule”? Not intentionally, but you never know. The links to the searches are above, and the data is free.