This week Hurricane Florence is making landfall in the southeastern United States. Sociologists know that the impact of natural disasters isn’t equally distributed and often follows other patterns of inequality. Some people cannot flee, and those who do often don’t go very far from their homes in the evacuation area, but moving back after a storm hits is often a multi-step process while people wait out repairs.

We often hear that climate change is making these problems worse, but it can be hard for people to grasp the size of the threat. When we study social change, it is useful to think about alternatives to the world that is—to view a different future and ask what social forces can make that future possible. Simulation studies are especially helpful for this, because they can give us a glimpse of how things may turn out under different conditions and make that thinking a little easier.

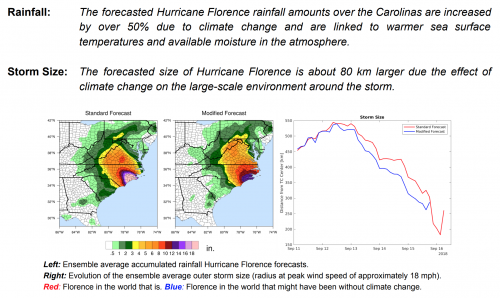

This is why I was struck by a map created by researchers in the Climate Extremes Modeling Group at Stony Brook University. In their report, the first of its kind, Kevin Reed, Alyssa Stansfield, Michael Wehner, and Colin Zarzycki mapped the forecast for Hurricane Florence and placed it side-by-side with a second forecast that adjusted air temperature, specific humidity, and sea surface temperature to conditions without the effects of human induced climate change. It’s still a hurricane, but the difference in the size and severity is striking:

Reports like this are an important reminder that the effects of climate change are here, not off in the future. It is also interesting to think about how reports like these could change the way we talk about all kinds of social issues. Sociologists know that narratives are powerful tools that can change minds, and projects like this show us where simulation can make for more powerful storytelling for advocacy and social change.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.