For better or worse, pop culture models some of our deepest assumptions about social relationships. One classic example is the Hollywood double standard when it comes to gender and aging—leading men get to age while the media expects most leading women to stay forever young. This can lead to age gaps on screen that mirror uncomfortable patterns of gendered power in society.

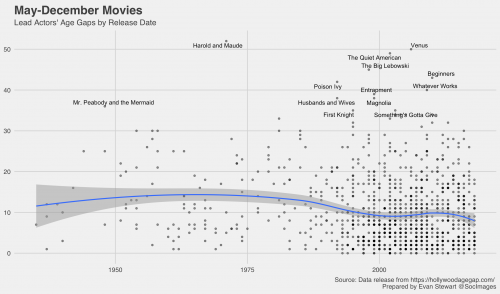

Has this trend gotten better or worse over time? I recently came across some great open data from the Hollywood Age Gap project, where Lynn Fisher has collected the ages of actors playing the romantic leads in over 600 films to calculate the actual age gaps behind the on-screen relationships. The website does an excellent job showing the gaps for each movie individually, but we can also look at them in the aggregate. It turns out that as more movies are produced, more also tend to have smaller age gaps between the leads. The average age gap for films in this data set sits just below 10 years since 2000, down from average gaps of about 15 years through the 1970s.

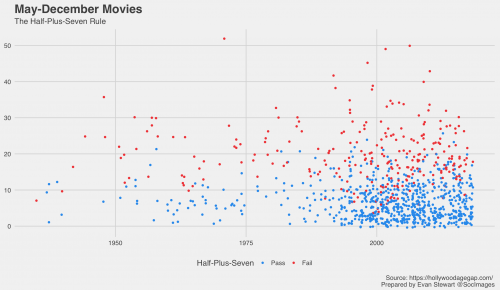

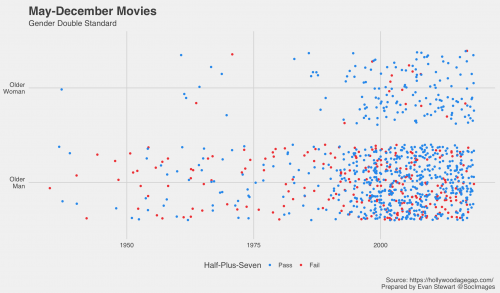

We also know that social context matters for relationships. If both people are older, for example, smaller age gaps aren’t as big a deal. The classic “half-your-age-plus-seven” shortcut is one example of the kind of informal rules cultures can develop to figure these things out. After a little math, I color coded the age gaps using this common shortcut. About 27% of the movies in this data set fail the test. Notice how the rule cuts both ways—some larger age gaps pass the test because both actors are older. Other smaller age gaps fail the test.

However, there is still a massive gendered double standard in these movies. Once we remove the 20 instances of same-sex relationships in the data set, 83% of the cases have an older man and only 17% of cases have an older woman. The older men cases are also more likely to violate the half-plus-seven rule (based on a quick chi-square test for gender of older actor x half plus seven status – p<.001).

The news here is a mixed bag. While average age gaps as a whole are on the decline, these data show how Hollywood still has a gendered double standard for who has to act in a potentially “creepy” scenario on screen.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.