As we’re sure you’ve noticed, one thing we’re really interested in is the social construction of gender and the way the world is divided into things that are ok for men to do and things that are ok for women to do. This dividing of the world by gender includes everything from food (salad vs. steak), pets (cats vs. dogs), and even colors (pink vs. blue). Generally, people are punished for not following these rules, though men are often punished more harshly for crossing into “feminine” or “girly” territory. At the same time, because these rules are socially constructed, they get fiddled with and sometimes people can get away with crossing the gender line–or even make it cool to do so.

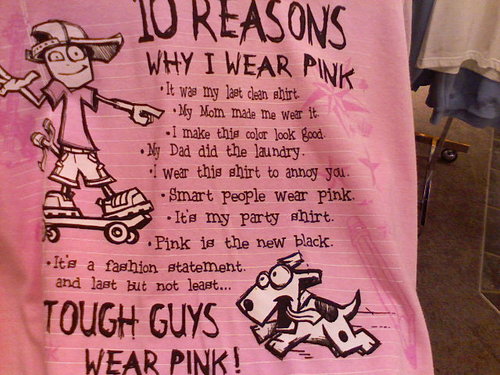

Abby sent in this photo of a t-shirt (found here) similar to one she saw a boy wearing at a school picnic recently. Another boy was also wearing a pink shirt, though without the explanation for why.

Abby says,

I think it is interesting the way the shirt challenges some dominant ideas about gender (pink = smart) while reinforcing others (e.g. men don’t know how to do laundry).

Another example of pink being redefined as an appropriate color for men to wear (other than Don Johnson in the 1980s) is Andre 3000 from Outcast (image found here):

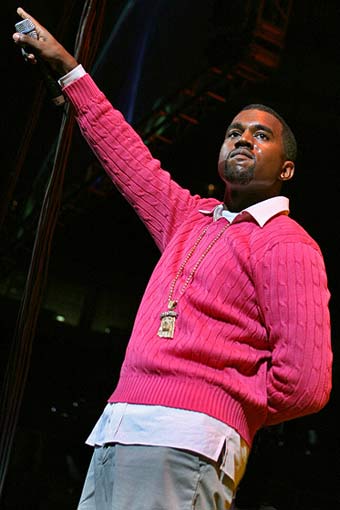

In fact, Andre 3000 was one of several hip-hop stars in the last few years who have clearly cared about fashion and re-popularized what has been described as a “dandy” fashion sense (see next photo, found here). So something that we generally associated with women (caring intensely about fashion) has become an acceptable, or even hip, part of a masculine image.

Here’s Kanye West in pink (found here):

Here is a picture (found here) of the character Chuck Bass from the TV show “Gossip Girl”:

Huh. While looking for other examples for this post I came upon The Charming Dandy, which has the tagline “a feminine eye for every guy.” It gives advice about fashion, manners, decorating, and tips for grooms (I did not previously know the names for shawl, peak, and notch lapels). The things you discover.

Anyway, these pics could be useful for showing how our gender dichotomy (pink = girls, blue = boys) is actually a lot more contradictory, that there is nothing “natural” about associating pink with girls, and that we often change gender rules while failing to acknowledge this has any bigger implications for our entire system of dividing the world by gender.

Thanks to Abby for the image and post title!