Last week marked the 154th anniversary of a conflict that would reverberate across the United States. Its history has been clouded by the American Civil War, leaving it often as a mere footnote in larger conflicts. Fighting in the Dakota Conflict unfolded over only six weeks, during which hundreds of Minnesota settlers were killed or displaced. However, it is the conflicts impact on the Dakota that has left the longest legacy. After the war, more than eight hundred Dakota men were sentenced to death and thirty-eight would be hung in Mankato in 1862 – still the largest mass execution in American history. More than 1,600 women, children and the elderly spent a winter interred on Pike Island on the Mississippi before being shipped to reservations in Nebraska. Disease and starvation was rampant. In another act of indignity, Congress passed legislation banning the Dakota from returning to Minnesota – a law that remains on the books more than a century and a half later.

Minnesota’s Dakota conflict has an undeniable place in American history. After many Dakota fled to the Dakota Territory, Henry Sibley (the first governor of Minnesota) led a military expedition to continue the fighting. The incursion has been called the opening of the infamous Plains Wars.

How have Minnesota and national newspapers portrayed this conflict and gauged its impact on the state and indigenous communities over the past 150 years? What narrative frames, definitions and moral evaluations of the historical event can we find in them? How has the representation of natives and the relationship between whites and natives shifted over time? A new research project at the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies tries to respond to these questions.

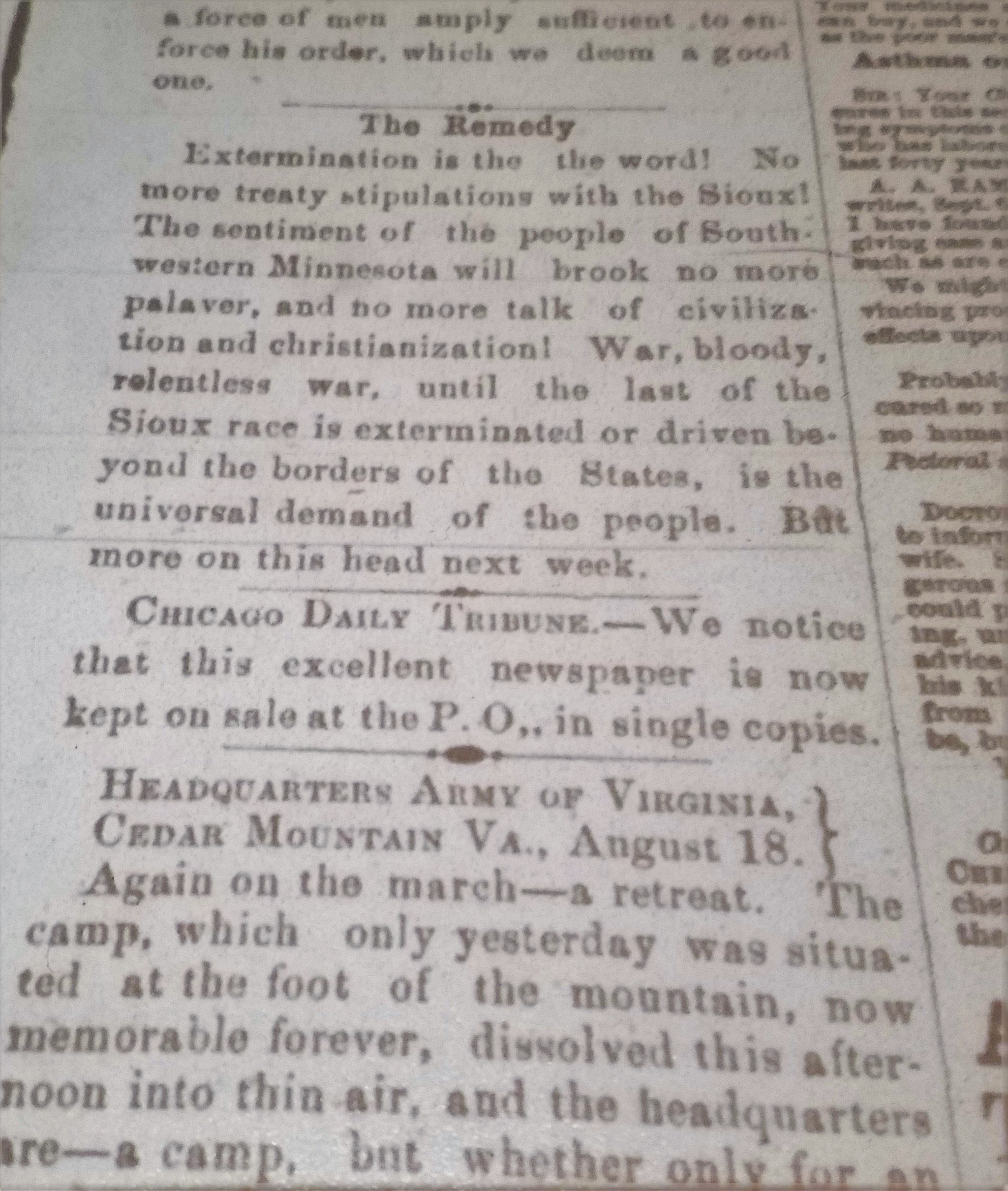

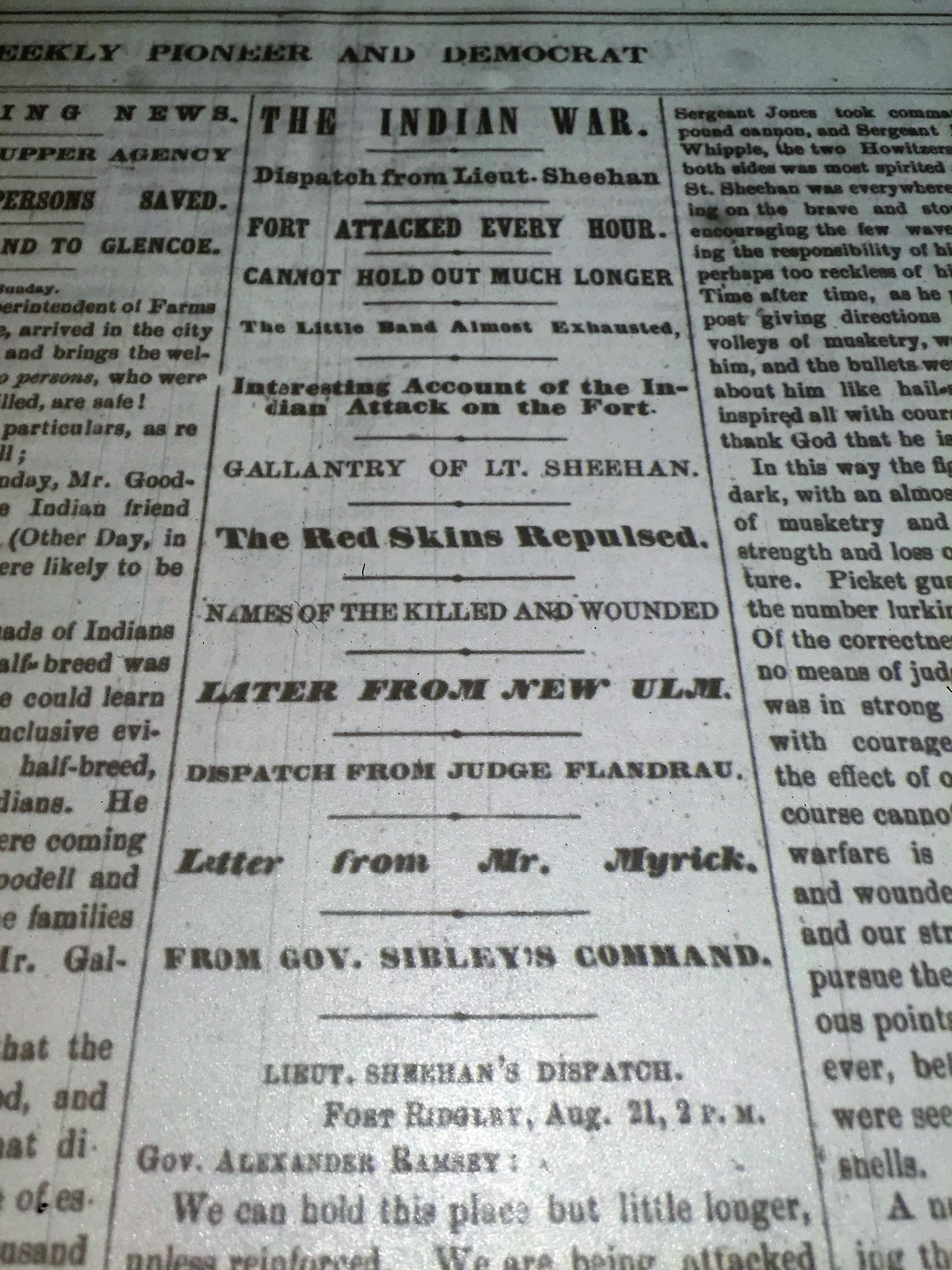

In the first 25 years references to “savage uprisings” and “massacres by the red-man” are commonplace, even in newspapers as far away as New York City. What’s more astounding is the amount of news space dedicated to the conflict, even during the height of the Civil War. In more recent years derogatory language has diminished and responsibility for wrongdoings has tilted towards the mainstream white society, with some calling the Dakota conflict and the subsequent forced removal an act of genocide. Minneapolis and several other communities have recognized it as such. But have those new interpretative frames and labels increased awareness of those events and fostered reparative measures? Once completed, this project will help the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies better equip teachers in Minnesota to discuss the Dakota conflict and its legacies in classrooms, ultimately providing greater awareness to a genocide that occurred in our own backyard. The work with K-12 educators is aimed at exploring how we accept, interrogate or question available representations of White–Native relations in Minnesota. As an outcome we will develop specific teaching resources designed to unpack the social messaging (narratives structures, positioning, stands, etc.) embedded in different historical representations of the US-Dakota War, from its occurrence to our present.

Comments