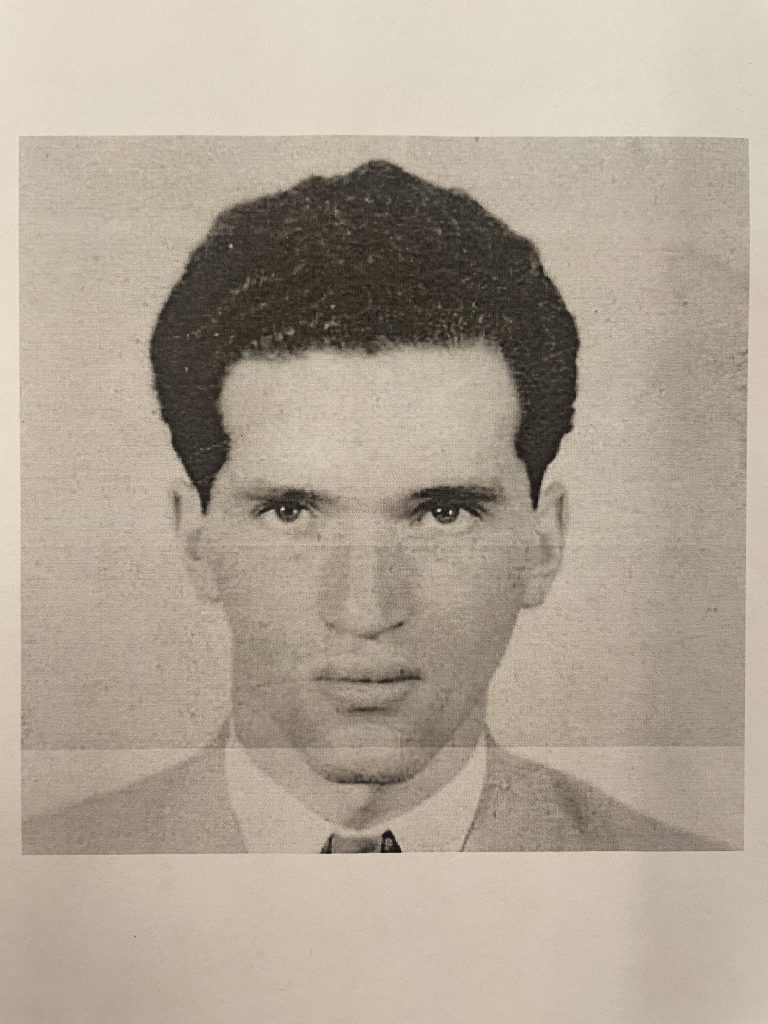

Charles Fodor is a Minnesota Holocaust survivor, one of the survivors whose arrival to the Twin Cities came over a decade after the end of the war. While many of the Holocaust survivors that immigrated to Minnesota did so in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, it was not uncommon for survivors to attempt to return to their prewar homes or, in the case of Charles Fodor, remain in their homes after they were liberated.