Dear Incoming Members of Congress from the Tea Party,

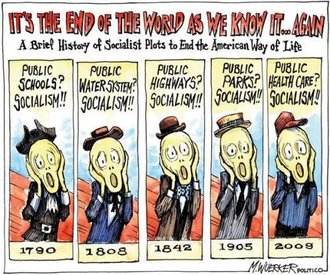

Do you like clean tap water? How about our scenic and toll-free interstate highways? Do you think 911 service and the fire department are neato?

Then you like taxes! Because taxes pay for all those things, and without taxes, we can’t have them. That’s not socialism–that’s civilization, built up over centuries of debate and experimentation in solving the problems that human societies face.

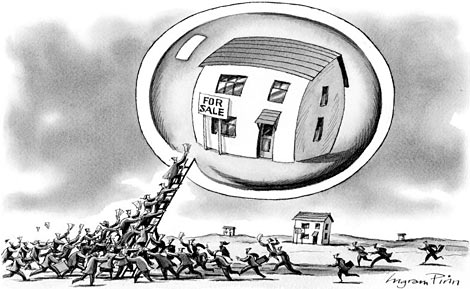

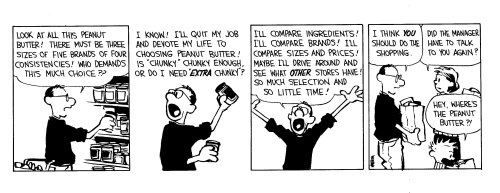

Have you considered what it would be like to return to a world in which your home would be allowed to burn down if you didn’t display a placard over your door indicating that you’d purchased the right kind of private fire insurance? Do you know why we don’t do that anymore? Because we tried it, and it didn’t work. Some problems cannot be reduced to individual property and individual risk—they can’t be privatized away.

Taxes aren’t a conspiracy to deprive you of your wealth. They pay for a lot of stuff you use. And don’t go all squidgy over the redistribution of those taxes to the poor. If you find them all undeserving, then remember that programs originally intended for them, like Social Security and Medicaid, are increasingly providing economic lifelines for middle- and upper-middle-class people too.

In fact, the richer you are in the United States, the more you make out like a bandit in terms of the benefits you enjoy versus your share of tax burden. Take it from a guy who is much, much richer than you will ever be:

There’s class warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning.

Now that we’ve got that cleared up, please send in the social conservatives. Salt N Pepa want to have a little chat with them about Don’t Ask Don’t Tell.

Sincerely,

Brooke