- So my apartment in Copenhagen got robbed this afternoon–while I was in it. Dudes broke down the door, walked right past a flat panel TV, and ignored the closed bedroom doors, behind which they would have found a couple of new, easily fence-able laptops. And me.

- Having ignored all the pricey and highly portable electronics, guess what they stole?

The living room light fixture.

Let me say that again: the light fixture. I won’t dignify it with the name chandelier. It wasn’t anything special as far as I could tell, but my upstairs neighbors tell me that it was probably a designer number worth about 8,500DKK–that’s around US $1,700.

The thieves stacked up the couches in the living room so they could reach the lamp where it hung from the ceiling, then cut the wires and took it away. Wrapped in my favorite (and only!) overcoat, which is the part that really steams me, since it’s about 30F outside and I have nothing else to wear.

After I got over the surprise, I was in awe at the absurdity of it all. Instead of being frightened (that part set in later), I found there was something strangely funny at the sight of the raw electrical wires hanging from the living room ceiling, with the flat panel TV a foot away.

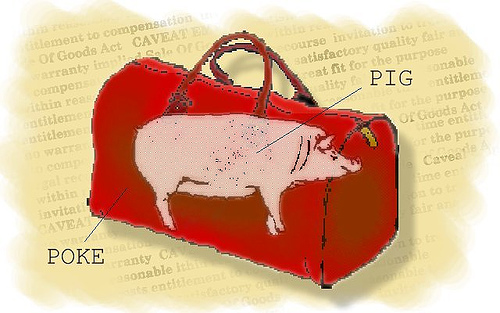

It just didn’t make sense economically. Who the heck breaks into a house to steal a light fixture? And who goes to that much trouble for it? Shattering the big, heavy front door so that the wood frame was splintered and the locks broken was not quick work. How could lamps be worth that kind of trouble?

But it gets even better: when I called the police, they said the whole neighborhood had been swept by a light-fixture-robbery gang today! In fact, they were so busy with these cases that they would not be able to come to my place to make a report for at least 24 hours. Apparently, there are gangs from Romania and Poland who steal pricey Danish light fixtures to resell outside of Denmark at a hefty profit. Heftier than the profit on a flat-panel TV? So it would seem.

So this got me thinking about other weird things people steal, and I knew in an instant that there must be a website or two devoted to this subject. After all, there are plenty of sites devoted to weird things people try to sell online. I figured theft must be closely related, and was not disappointed. Here are some highlights:

- 27 buttons: Felicidad Noriega, former first lady of Panama, was arrested for stealing the buttons, which she clipped off jackets as she walked through a Burdines department store in Miami; note that she didn’t take the jackets…just the buttons, making the jackets unwearable for anyone else

- handful of communion wafers: grabbed during Mass by a guy who simply tried to walk out, past the dozens of outraged congregants; that ended about as well as you’d expect

- 93 severed ponytails: stolen by a fellow posing as a representative for the Locks of Love charity; his unsavory purposes remain mercifully obscure

- $15,000 worth of breast pumps: stolen by two men; what a pair! Let it be noted that this theft, along with the ones involving buttons and communion wafers, was committed in Florida…Coincidence? You decide.

- a 50lb halibut named Big Mamma: the thief broke into the California Halibut Hatchery, speared the star attraction (as close to a local celebrity as a fish could be), threw her on the grill, and served it to his guests, like some modern-dress version of the Feast of Thyestes; the thief’s attorney said later, “I tell you, it was as if he had barbecued Bambi. People want to put him in the gas chamber.”

What are people willing to pay for, and what are they willing to steal? This ends up being an economic sociological question, because it ties into what people value. I didn’t even notice the lamp that a group of men broke down a door and risked arrest to steal. I can’t really remember what it looked like. But I’ll always miss my beloved overcoat, which they probably regarded as a rag–no different from a cheap towel or a throw rug, useful only in concealing the real goods.

In memory of Coat: RIP, old friend.

UPDATE!

My neighbor’s estimate of the lamp’s value was waaay low: turns out I was living with an interior design masterpiece and had no clue: the thing was a 1958 Poul Henningson “Artichoke” lamp, valued at 39,000DKK, or about US $8,000. Unbelievable. Had anyone mentioned this to me, I would have a) paid more attention to it, and b) made sure I didn’t leave anything valuable in the house, ever. In fact, I probably would have moved to a place that didn’t contain such a juicy target for thieves. Dang. Hard way to learn the difference between IKEA and “real” Danish modern.

Shortly after posting

Shortly after posting