Visiting a museum in the Turkish city of Antalya a few years ago, I was startled to find–among the Greek and Roman sarcophagi–the tomb of a dog. The monument, for a dog named Stephanos, was discovered near Termessos in 1998, not far from the inscribed sarcophagus of Rhodope herself. The epitaph on Rhodope’s tomb–written in ancient Greek, like the one on Stephanos’ monument–states that she paid for her grave marker entirely by herself, which suggests that she was single. And wealthy.

It is not surprising to know that ancient people loved the animals who lived with them. But it was surprising to find that spending a lot of money on pets, which is commonly thought to be a recent phenomenon, is really nothing new. In the contemporary United States, the vast majority of households count pets among their members (63 percent as of 2006), and spend lavishly on their care: $43.2 billion in 2008, up from $23 billion in 1998. These figures break down as follows:

Food………………………………………………….$16.8 billion

Supplies/OTC Medicine………………………..$10.0 billion

Vet Care…………………………………………….$11.1 billion

Live animal purchases………………………….$2.1 billion

Pet Services: grooming & boarding………..$3.2 billion<

Data from American Pet Products Association market research.

No data were available on expenses for sarcophagi, but animals seem to be playing a part in the economic surge of the American funeral industry. A simple pet cremation starts at $185, with additional charges for a burial, procession, and grave marker; apparently, one bereaved “pet parent” (the preferred term in use by funeral directors) paid $5,000 for a bronze sculpture of the deceased to mark the dog’s grave. Which brings us back to Rhodope, a woman of the ancient word, and her beloved dog Stephanos.

The limestone structure I saw in the Antalya museum was shaped like a modern doghouse, but with a roof ornamented like an ancient temple. The narrow front end of the tomb bore the inscription, which seems to have consisted of three epigrams; the first can no longer be read, but the second two have been translated thus:

(I) was Rhodope’s happiness.

Those who played with me

Called me lovely Stephanos.

Rhodope shed tears when I perished,

And buried me like a human.

I am the dog Stephanos,

And Rhodope set up a tomb for me.

The sight of Stephanos’ tomb was so moving, because so unexpected: I had never heard that the ancient Greeks buried their dogs (or other animals) with sarcophagi and poems. But a little poking around on the internet revealed that the tomb of Stephanos was far from unique, but rather on the more elaborate end of a spectrum of such practices.

Here are some other texts, taken from ancient dogs’ gravestones, presumably on display elsewhere in the world (I am indebted to this blog for the texts):

- Thou who passest on this path,

If haply thou dost mark this monument,

Laugh not, I pray thee, though it is a dog’s grave.

Tears fell for me, and the dust was heaped above me

By a master’s hand.

This epitaph reminds me of Argos, Ulysses faithful dog in the Odyssey, who was the first to recognize the returning king after 10 years’ absence from Ithaca:

- This stone holds the white dog from Melita,

The most faithful guardian of Eumelus;

Bull they called him while he was yet alive

But now his voice is ‘prisoned in the silent pathways of night.

I particularly love this last epitaph because it’s so easy to imagine how the dog memorialized in it would be pleased to know that she still scares the animals she used chase on the mountainside when she was alive:

- Surely even as thou liest dead in this tomb

I deem the wild beasts yet fear thy white bones, huntress Lycas;

And thy valour great Pelion knows,

And splendid Ossa and the lonely peaks of Cithaeron.

All this love and expenditure directed at dogs reminded me of Leona Helmsley, the wealthy American businesswoman who left the bulk of her multi-million-dollar estate to her white Maltese, Trouble. When Helmsley died in August, 2007, she had four living grandchildren, two of whom she left nothing; the other two received $10 million each. But Trouble–the dog notorious for biting everyone except Helmsley–got a trust fund worth $12 million, and the right to be buried in the Helmsley mausoleum next to Leona. Helmsley’s brother also received a bequest of several million dollars–to pay for his services as Trouble’s primary caregiver!

- Leona Helmsley and Trouble: a modern Rhodope and Stephanos?

I had to wonder why we never seem to hear about such extravagant expenditures on animals other than dogs. Where are the monuments to the faithful and affectionate rabbits? Or to the long-lived and highly-intelligent African grey parrots? Maybe such memorials exist, but since there are so many more dogs living with humans compared to other kinds of animals (75 million as of 2008, in the US alone), that when we read about funerary monuments for pets, odds are that the story will concern a dog. Your thoughts?

To see more on the sociological study of human relationships with animal companions, click here.

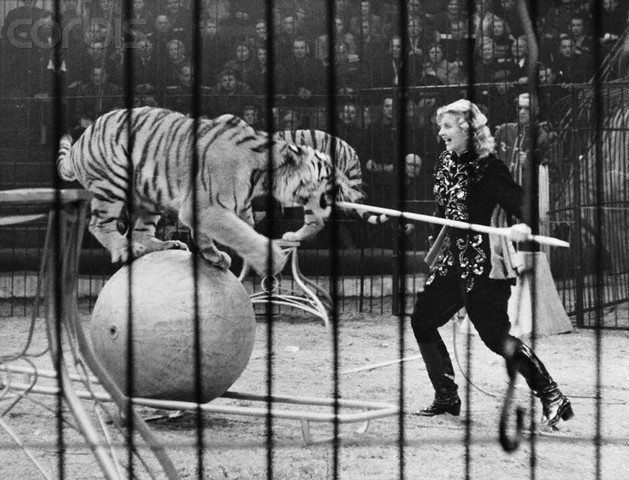

Once upon a time, the phrase “The Lady or the Tiger?”–taken from an 1882

Once upon a time, the phrase “The Lady or the Tiger?”–taken from an 1882

st a generation ago. As in the early days of AIDS, the sources of the current crisis are poorly understood but its fatal effects are all too evident–a toxic combination that has spread fear around the world. We’re witnessing a kind of global infection among our social and economic institutions, and may need to start thinking like epidemiologists—the scientists who fight the spread of AIDS and other diseases

st a generation ago. As in the early days of AIDS, the sources of the current crisis are poorly understood but its fatal effects are all too evident–a toxic combination that has spread fear around the world. We’re witnessing a kind of global infection among our social and economic institutions, and may need to start thinking like epidemiologists—the scientists who fight the spread of AIDS and other diseases