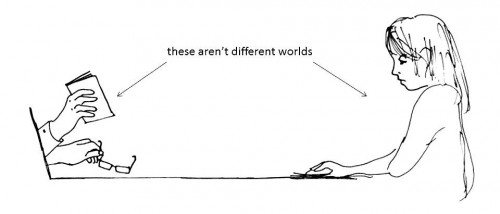

In part 1 I opened with a run down of the different kinds of “digital divides” that dominate the public debate about low income access to technology. Digital divide rhetoric relies on a deficit model of connectivity. Everyone is compared against the richest of the rich western norm, and anything else is a hinderance. If you access Twitter via text message or rely on an internet cafe for regular internet access, your access is not considered different, unique, or efficient. Instead, these connections are marked as deficient and wanting. The influence of capitalist consumption might drive individuals to want nicer devices and faster connections, but who is to say faster, always on connections are the best connections? We should be looking for the benefits of accessing the net in public, or celebrating the creativity necessitated by brevity. In short, what kinds of digital connectivity are western writers totally blind to seeing? The digital divide has more to do with our definitions of the digital, than actual divides in access. What we recognize as digital informs our critiques of technology and extends beyond access concerns and into the realms of aesthetics, literature and society. I think it is safe to say that most readers of this blog think they know better: Fetishizing the real is for suckers. The New Aesthetic, a nascent artistic network, is all about crossing the boarder between the offline and the online. Pixelated paint jobs confuse computer scanners and malfunctioning label makers print code on Levis. The future isn’t rocket-powered, its pixelated. Just as the rocket-fueled future of the 50s was painstakingly crafted by cold warriors, the New Aesthetic of today is the product of a very particular worldview. The New Aesthetic needs to be situated within its global context and reconsidered as the product of just one kind of future. more...