Discussing the relative strengths and weaknesses of education as it occurs on and offline, in and outside of a classroom, is important. Best pedagogical practices have not yet emerged for courses primarily taught online. What opportunities and pitfalls await both on and offline learning environments? Under ideal circumstances, how might we best integrate face-to-face as well as online tools? In non-ideal teaching situations, how can we make the best of the on/offline arrangement handed to us? All of us teaching, and taking, college courses welcome this discussion. What isn’t helpful is condemning a medium of learning, be it face-to-face or via digital technologies, as less real. Some have begun this conversation by disqualifying interaction mediated by digitality (all interaction is, by the way) as less human, less true and less worthy, obscuring the path forward for the vast majority of future students.

Discussing the relative strengths and weaknesses of education as it occurs on and offline, in and outside of a classroom, is important. Best pedagogical practices have not yet emerged for courses primarily taught online. What opportunities and pitfalls await both on and offline learning environments? Under ideal circumstances, how might we best integrate face-to-face as well as online tools? In non-ideal teaching situations, how can we make the best of the on/offline arrangement handed to us? All of us teaching, and taking, college courses welcome this discussion. What isn’t helpful is condemning a medium of learning, be it face-to-face or via digital technologies, as less real. Some have begun this conversation by disqualifying interaction mediated by digitality (all interaction is, by the way) as less human, less true and less worthy, obscuring the path forward for the vast majority of future students.

This is exactly the problem with the op-ed in yesterday’s New York Times titled, “The Trouble With Online Education.” Far from making a convincing case that online education should trouble us, Mark Edmundson instead makes a case for interactivity. He does this by contrasting brilliant lecturers who can read a room when face-to-face against completely non-interactive online course templates. Sure, the former has advantages over the latter, but is this really the choice faced by universities, professors and students today? Of course not.

Edmundon’s first error is having nostalgia for a fiction past where the Web didn’t exist and professors were always there with the students in the room, face to face, making the lecture an in-the-moment responsive operation, always guided by the changing currents of the classroom. The varying interests and needs of the students were perceived by the professor’s magical “pedagogical sixth sense” (Edmundson’s term) and the speech would morph accordingly like a work of performance art. Beautiful! Unfortunately, as just about anyone who has ever taken a college course ever knows well, a whole bunch of face-to-face lecturers also created very non-interactive courses. Edmundson describes an ideal but presents it as a norm.

Then, Edmundson describes an online course. He describes them as courses finished before they are started; the text is pre-written and video lectures pre-filmed. Online courses are made out to be like freight trains that propel forward upon a pre-determined track, irrespective to the needs of the particular students enrolled. While this actually reminds some of us of the offline-only courses we took in the past, the bigger point is that this is not how online education needs to be done.

The real argument that Edmundson is making, and it is actually a good one, is that there are pedagocial benefits to interactive and responsive learning environments. Where he fails is wrongly assuming that human interactivity is solely the business of the offline and impossible online. This is plainly false.

The easier argument is actually discussing the difficulties of being interactive when teaching face-to-face. For example, sometimes professors are over-worked or uninterested in interacting with students and sometimes the classrooms are too large to be intimate. Building interactivity into online education, on the other hand, is actually less mysterious and less likely to require some magical sixth-sense. Using the digital, and social, technologies that so many of the students and professors already know much about is the obvious start. There is a whole literature being written about how to use discussion boards, wiki’s, blogs, Twitter and other tools when teaching online and offline courses.

What I’d rather conclude on is drawing a more abstract point from this specific discussion. Let’s look closely at the rhetoric Edmundson uses to develop his argument disqualifying online education:

in real courses the students and teachers come together and create an immediate and vital community of learning. A real course creates intellectual joy, at least in some. I don’t think an Internet course ever will. Internet learning promises to make intellectual life more sterile and abstract than it already is — and also, for teachers and for students alike, far more lonely. [emphases added]

Straight out of the link-grabbing and substance-lacking playbook of Sherry Turkle or Steven Marche, Edmundson ends with the argument that the Internet is making us lonely. This is an argumentative strategy that plays well, generates lots of page-views and comments, and is thoroughly unsubstantiated by research. And like all the other popular pieces claiming the Internet is making us lonely, the argumentative strategy is to contrast the Internet with the “real.”

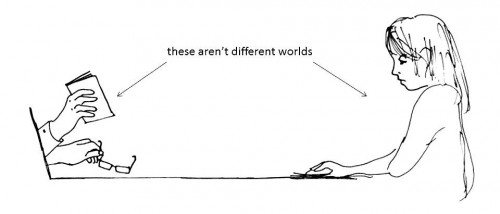

This is my biggest complaint about tech-writing: the understanding of that which is mediated by digital information is somehow not real. The offline is described as human, filled with “joy” and “community” and all the intangibles related to our messy IRL existence. Conversely, the online is “virtual,” “sterile” and apparently comprised of bored and frowning teenagers, as the article’s lead illustration seems to suggest. This understanding of a “real” world separate from this other “virtual” world is popular and, I think, fundamentally wrongheaded.

I’ve previously coined the phrase “digital dualism” to describe false separation of the on and offline, and, in this case, it is via this dualism that Edmundson justifies his claim that interactivity can only happen offline. The logic is that offline is a space pregnant with human connection, the online is a space where students are met with algorithms and robots; without human connection there can be no true interactivity. I recently described this faulty logic “The IRL Fetish” (IRL = “in real life”), to mistake real human interaction as only existing “IRL” and missing the degree to which digital tools do not whisk us to some new virtual space but are rather part of our one, lived, augmented, human reality. To fetishize the offline as the sole domain of humanity is to obscure the fact that our digital tools are also comprised of real people, with real histories, politics, standpoints, ideas and potential. That which happens online is real, it is human; online education does not preclude real connection, community or interactivity.

What are the consequences of fetishizing offline education? Who benefits from disqualifying all education that does not happen purely face-to-face as less “real”? What does that view say of the many teachers and students making use of some combination of on and offline learning tools? Is that pedagogy less real? Are the student’s insights less real? Let’s not begin this by belittling learning communities that, to some degree, use or don’t use digital tools. Let’s drop this false binary between the online and offline and recognize that, instead, they are both real. From here we can start the more important discussion of how to teach, both on and offline, in our ever changing real world.

Comments 17

Online Education is Real Education » Cyborgology | For Teaching Online | Scoop.it — July 20, 2012

[...] [...]

Peter Laird — July 20, 2012

I personally believe my kids (3 and 5 yr old today) in the future will go to brick and mortar universities, but some of the courses (e.g. the big lecture-based 101 courses) will be delivered using an online experience augmented with in-person office hours. So its not correct to assume that all online learning is necessarily devoid of face-to-face interaction. Seems like another false assumption in the article that online education is necessarily remotely delivered.

Mike — July 20, 2012

Nathan,

The wording in Edmundson's last paragraph is problematic. I'm not sure, though, that he meant to make an ontological claim in using the word "real." It seems that he was making a qualitative claim instead (with which we may or may not agree). For example, when someone says something like, "A real football player would ..." I don't think they necessarily mean that other football players are not real. They're saying something about the ideal type rather than discounting the existence of the others. That said, it may not have been the best word choice.

Your opening paragraph mentions many of the sorts of questions that we need to be asking about online education. I think Edmundon is most generously read as making an attempt to explain one of the pitfalls, in his view, of online education. You're certainly right that he depicts an ideal, but I wouldn't label this as nostalgic. Many traditional classrooms fall considerably short of the ideal, but it is not an unrealizable or impossible ideal either. I've been on both ends of classrooms that achieve what Edmundson describes.

Without claiming that that all online education is by default worthless or that no interaction can take place online, it is still worth asking whether the online environment makes it harder to achieve the kind of camaraderie and density that the traditional classroom at its best can offer. I would agree that Edmundson's piece does not quite rise to the level of a convincing argument (and he claims too much in his closing lines). But others have done a better job at that. I'm thinking of Hubert Dreyfuss' application of his theory of embodied skill acquisition to educational environments (I summarized it, inadequately, here: http://bit.ly/ur49S7). I think Dreyfuss raises substantive claims, grounded in an understanding of embodied cognition, that ought to be taken into consideration when we think about the relative merits of online education.

It is true, though, as you point out, that even if we recognize some particular features of the ideal, we are not always at liberty to pursue it and we must make the best of the cards we are dealt. Moreover, there is a great variety of platforms and tools that make for what we might call online or digitally enhanced education, and these need to be taken on their own terms. Some are better than others. Additionally, we should consider that some professors and some students will be temperamentally disposed to prefer one medium over the other.

One last point, I am concerned that we might be tempted to reduce education to fit the medium. Online environments privilege certain modes of knowledge and skill over others. Are we in danger of conforming "education" to what the medium can accommodate? Of course, it is true that face-to-face environments likewise privilege certain modes of knowledge and skill. Part of the conversation needs to include a discussion of what kinds of knowledge and skill are best imparted by online environments and which are best imparted in face-to-face settings.

All of this to say that there's a lot of work left to be done in sorting out this very important set of issues. Thanks for addressing it here.

Online Education is Real Education « n a t h a n j u r g e n s o n — July 20, 2012

[...] This post originally appeared on Cyborgology – read and comment on the post here. [...]

Online Education is Real Education » Cyborgology | Educational Technology in Higher Education | Scoop.it — July 22, 2012

[...] Discussing the relative strengths and weaknesses of education as it occurs on and offline, in and outside of a classroom, is important. Best pedagogical practices have not yet emerged for courses primarily taught online. What opportunities and pitfalls await both on and offline learning environments? Under ideal circumstances, how might we best integrate face-to-face as well as online tools? In non-ideal teaching situations, how can we make the best of the on/offline arrangement handed to us? All of us teaching, and taking, college courses welcome this discussion. What isn’t helpful is condemning a medium of learning, be it face-to-face or via digital technologies, as less real. Some have begun this conversation by disqualifying interaction mediated by digitality (all interaction is, by the way) as less human, less true and less worthy, obscuring the path forward for the vast majority of future students. [...]

Two items/perspectives re: online learning — July 23, 2012

[...] the other side: Online Education is Real Education — from The Society Pages by Nathan [...]

Negotiating the Future of the Augmented Library » Cyborgology — July 28, 2012

[...] other as somehow more real or more authentic. As Nathan Jurgenson pointed out earlier this week in his piece on augmented education, false binaries ultimately lead us nowhere useful. When we consider learning, books, research and [...]

Scott Mandel — July 30, 2012

I am a firm believer that certain subject matters CANNOT be correctly or effectively be taught online. That being said, online education WILL surpass face-to-face as the preferred educational method for both teachers and students the not so distant future. Although, both online and offline education each have distinct and unchallengeable benefits, online learning offers relates more with our youth today.

1. Humans learn more effectively when they are ready and willing to learn (Push vs Pull), especially children.

2. Students demand convenience, online offers a way to learn early every subject matter at a click of the button.

3. Technology. Everyday new innovations and advancements are quickly closing the gap held by offline learning. Google Fiber, a high speed internet project being launched in Kansas City is an example. By offering speeds 100x fast than what is currently available (https://fiber.google.com/about/). Imagine the educational possibilities…

Quite frankly I feel that most educational professionals and Edmundson deny this “changing of the guard” because the fear the unknown and the potential repercussions of this movement that could leave them behind.

Scott

Tools für eine Offline-Diät | Social Media Club — August 1, 2012

[...] mit strikten Regeln und der kategorischen Trennung zwischen on- und offline (obwohl es eine einzige Realität gibt, wo sich die beiden ineinander [...]

Deborah Ash, PhD (Twitter @debiash64) — August 6, 2012

Thank you for an articulate and strong article in support of real online education; or should I say - real education in general. As you pointed out, it comes down to interactivity. As an online professor and instructional designer for online learning, I can attest that online education can be "real", interactive, engaging, and sometimes result in more transference of knowledge than a traditional classroom. It comes down to the design of the course and program, the training of the faculty, the support of the learners, and the content provided. I received my Master's and Doctorate degrees from Capella University (online) and a friend went to a traditional university for the same degree program. In a conversation with her after the Harkin report was released she pointed out that my knowledge "well" of instructional design and educational psychology practice and theory was deeper than her's. Are all faculty cut out to teach online? No. Are all students cut out to take online courses? No. The key is making sure everyone involved knows that. Kudos for pointing out what to so many of us in the field are trying to convey!

The impersonal technology assumption | ClintLalonde.net — August 9, 2012

[...] is simply not true (and thank you Nathan for pushing back against Mr. Edmundson with far greater clarity and eloquence than I can muster). The real argument that Edmundson is [...]

To Be or Not to Be? | capitalizing on knowledge — September 23, 2012

[...] Online Education is real education: http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/07/20/online-education-is-real-education/ [...]

Masters Degree Quality — January 5, 2013

[...] about the opportunity forum where a person can both become a management [...]

Growth of a business with a skilled staff — March 22, 2014

I totally agree with the fact that online education is real education. This is the most convenient sort of education.

Online education develops the student's skills — April 23, 2014

Hmm.. I think this is a great post. Online education helps the student to develop their skills. Great job!!!!