This piece was supposed to be about porn star James Deen.

This piece was supposed to be about porn star James Deen.

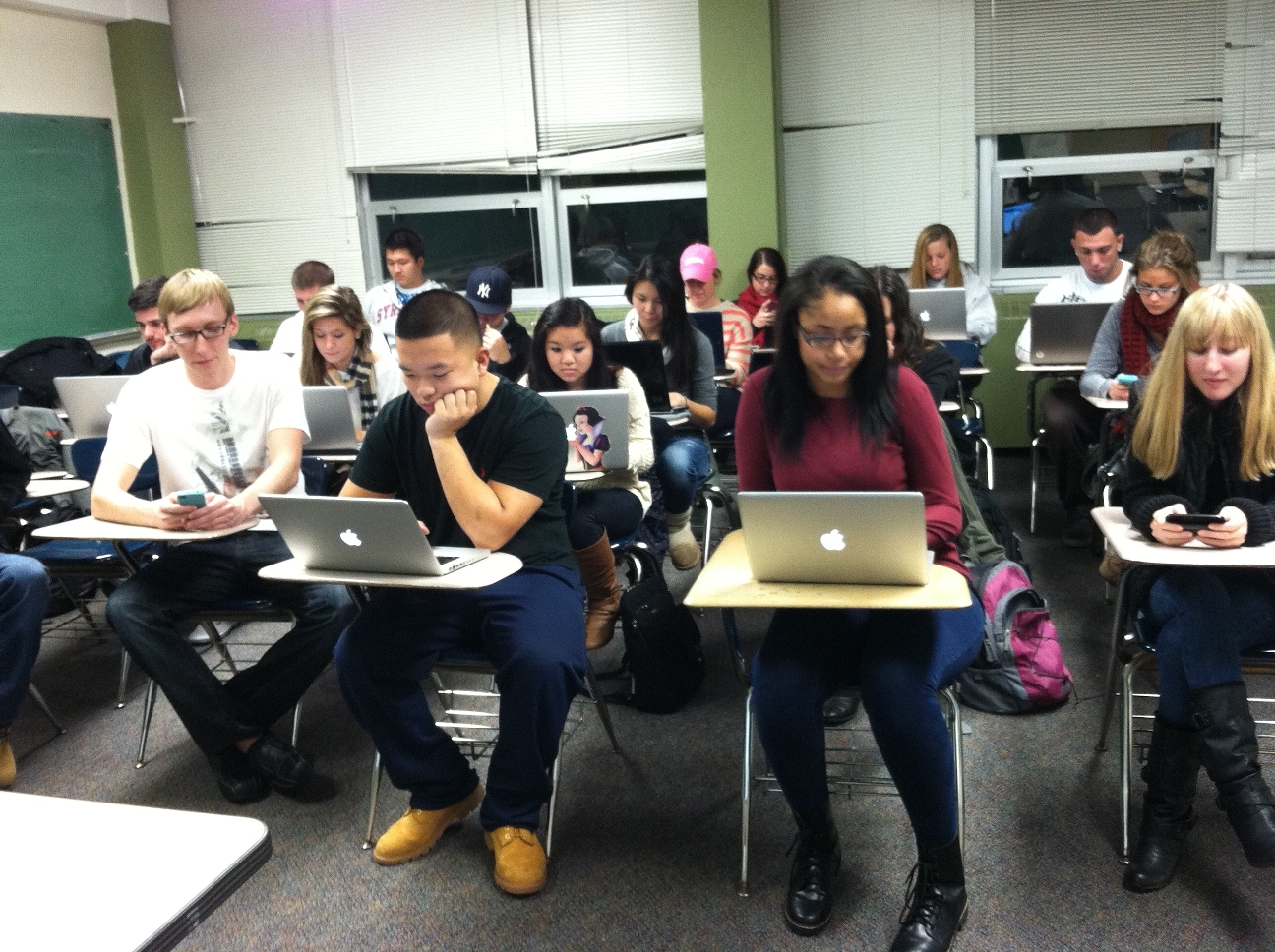

After reading about Deen here and there and everywhere, I had the idea that perhaps there was something worth writing about. Only the problem was, that the more I watched of his work, the less I had a desire to write about it. Perhaps the point is not Deen himself and how he has been lauded via the wheel of favorable ratings by female audiences online. What needs to be written about is what happens when a woman sits down and engages with sex—specifically, her own, as tied to an exploration of her individual sexuality and liberation therein—via the medium of a computer screen. more...

The online magazine Slate recently ran an

The online magazine Slate recently ran an