Start at 13:42 – 15:37 for images of Zuccotti Park being dismantled

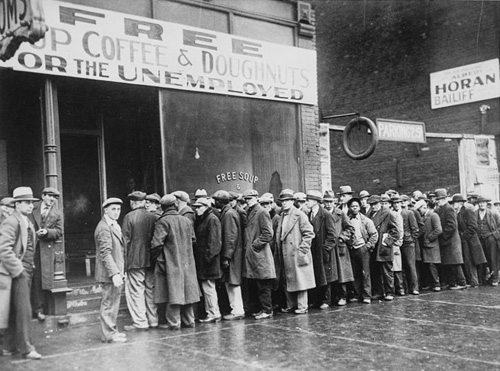

The clearing of the Occupy Wall Street demonstrators from the streets of various cities over the past few weeks has been a strikingly naked demonstration of the characteristic properties of what Jacques Ellul called “technique.”

Like other philosophers, Ellul thought of technology more as a state of being than as a collection of artifacts. “Technique” is the word he used to describe a phenomenon that includes, in addition to machines, the systems in which machines exist, the people who are enmeshed in those systems, and the modes of thought that promote the effective functioning of those systems.

In The Technological Society, Ellul called technique “the translation into action of man’s concern to master things by means of reason, to account for what is subconscious, make quantitative what is qualitative, make clear and precise the outlines of nature, take hold of chaos and put order into it.” The machine, he added, is “pure technique… the ideal toward which technique strives.” more...