So Tuesday night’s big reveal of Xbox One – Microsoft’s new incarnation of their console – appears to have been a disaster of spectacular proportions. This is interesting in itself, though not totally unexpected; people often react to new things in less than positive ways. But what’s especially interesting are the things that Microsoft got wrong and the specific elements that people are finding so problematic. On Microsoft’s part, they first amount to a baffling inability to understand the actual living situations of its own market, but they also amount to the continuation of a trend that I’ve written about several times before, namely: the worrying inclination of companies and their designers to remove agency from tech owners.

In other words, owners increasingly = users.

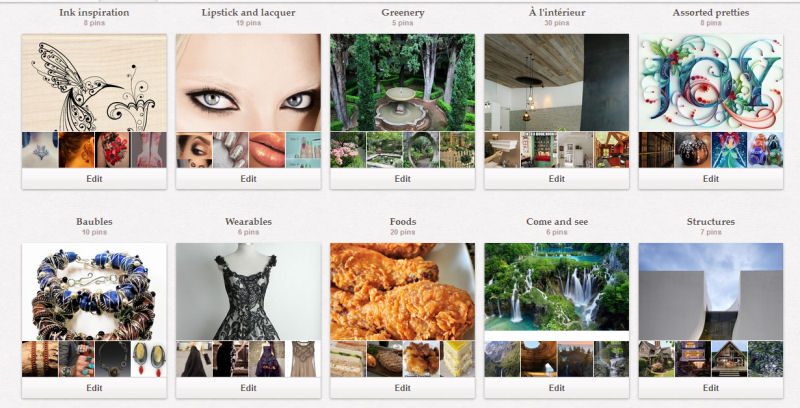

The first – and again, baffling – problem about the reveal was that the new Xbox appears to have been designed for the world of ten or fifteen years ago, a pre-tablet and smartphone world where people have an entirely different relationship with their TVs. The TV is the center of what Xbox One is and does; the reveal seemed to focus just as much on new ways to watch TV shows as it did actual games that one might use it to play. In other words, Microsoft appears to be attempting to sell a game console by marketing it as something other than a game console – which is puzzling. Even more puzzling is who Microsoft appears to think their market is: People with large TVs and large living rooms (that can handle a Kinect, which is now a required component of the console; more on that in a minute) and lives that might conceivably revolve around a TV in the first place rather than a smartphone or an iPad. In a post for Gamasutra, Leigh Alexander takes particular issue with this:

[B]y the end of the console event, I sat disoriented, feeling like I’d seen one of the Big Three take a hard left into a past decade, a fictional privileged nation where everyone owns a giant television they want to talk to, where they entertain themselves with high-end fictional simulations of football season and futuristic, nebulous wars abroad. Where we supposedly want whole-body play. Where the fantasy is that all our living rooms are big enough for that.

This is a catastrophic misconception of how the lives of my generation – Millennials – tend to look and how we tend to use our technology. Maybe our parents had big living rooms and big TVs that were the centerpiece of the house; we carry around small, nimble, intensely portable devices through which we consume a growing percentage of our entertainment media. In essence, Microsoft – a tech company, by no means always bad at what they do – made it look as though they have literally no idea what the digital side of our lives looks like. Alexander again:

My parents and their Boomer friends have those theoretical American homes, the kind with the spacious sofa and the dominant television altar, where they mainly watch on-demand recordings of cable shows…I’ve got friends who love immersive worlds and epic battles, sure. They have thousands of dollars in student debt and tiny, impermanent living spaces; their generation isn’t exactly about to broadly become the next generation of home owners. We play games on consoles and we watch shows on television and we Skype and Tweet from laptops, netbooks, iPads, PCs.

I live in a basement. I’ve lived in a basement for the last four years, because I’m in graduate school and it’s what tends to be most conveniently available in my area. A Kinect is not on the table for me, even if I wanted it (I don’t). The living situation of most of my friends looks similar.

And hey, about that Kinect – apparently it’s always listening to you. Even when it’s “off”. Which isn’t necessarily as creepy as it sounds, but.

The second major – and, I’d argue, most important – thing about which gamers are up in arms is the degree to which a number of features seem to limit the control an Xbox One owner has over their own machine. First and foremost, the device will apparently require regular internet connectivity – not constant, but regular – in order to work. As usual, no one speaking in any official capacity is calling this DRM, because no one likes to officially label anything DRM, but it feels uncomfortably close to the kind of always-on feature that made SimCity such a disaster. A number of people have pointed out the practical issues with this: what about people who live in areas where broadband internet is sparse or nonexistent? What about people like members of the military stationed overseas, for whom gaming is often a valuable form of recreation?

But aside from even the practical issues, this is yet another instance of someone buying something but not really owning it – not being free to set the terms under which it’s used. It doesn’t matter to Microsoft if you want to play Call of Duty (primary selling point: now there’s a dog!) offline in single-player campaign mode. If you have no internet for any significant length of time – say, a day or more (as yet the actual timeframe is unclear) – that’s not happening. No dog for you.

Added to this, it doesn’t appear that the console will allow players to easily make use of used games, given that it won’t run games off of a disc (Microsoft is apparently working on a digital trading service). And then there’s the mandatory Kinect thing. All of these problems amount to a console that you pay for but don’t really control. Which isn’t new – I own a PS3 and I can either “choose” to install firmware updates or to be unable to play any new games – but it’s another step down the road.

But I’m actually pretty happy. Why? Because people are making a stink about this. People still care. Losing control over something they pay for is not an attractive prospect to them. As long as at least some people regard this state of affairs as unacceptable, I think there’s hope.

Don’t talk about it too loudly, though. The Kinect is listening.

Sarah flails their arms for the camera on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry