A note: I’m using terminology like “digital space” and “online” in this piece, though I think those terms are problematic for a number of reasons.

I recently – and finally – joined Pinterest.

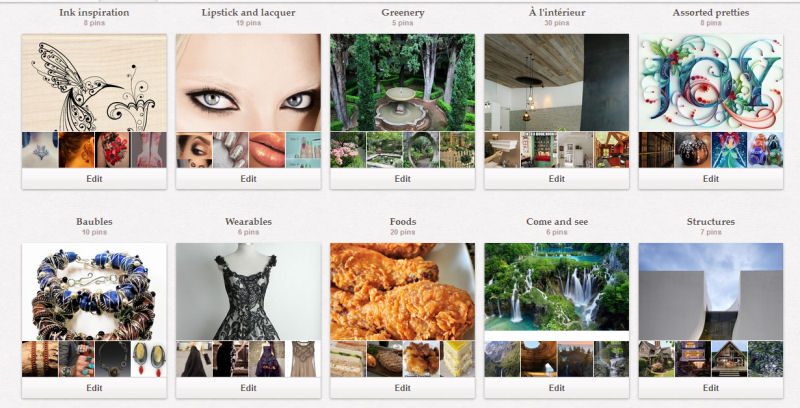

I’m not an early adopter when it comes to things like this, simply by nature. I have Tumblr for my knee-jerk reposting and for a while I didn’t really think that Pinterest had much to offer me. But what the hell, I’m finally there, and… Just look at the top of the page. That’s my account. That’s what it looks like. Except because of how I cropped it you can’t see the board that’s specifically for cute animals.

There’s a stereotypical Pinterest user and I can’t escape the feeling that it is what I have become.

But why does that matter? It matters for reasons of gender, for what it means to perform gender in a digital context, for how we understand the fluidity of gender within the different affordances of different kinds of social media. And in order to talk about that, I’m going to jump back about fifteen years and do some more navel-gazing. Bear with me.

I identify as genderqueer. What that means for me specifically is that I experience gender as a profoundly fluid thing; it is, among other things, something I put on when I get dressed. Which is true for everyone, actually, but my own understanding of who I am and how I’m going to perform my gender right now today can change dramatically depending on whether or not I decide to wear a skirt. For example. I move around a lot but generally I feel more internally masculine than feminine (for what it’s worth, I’m not that picky about pronouns).

When I was first constructing the digital aspects of my augmented life, I was able to explore my own gender-fluidity in entirely new ways, long before I had the necessary vocabulary to articulate what I was doing. I got involved in fandom, which was the first community I had ever been in that was explicitly welcoming of queer folk. I started roleplaying online, and I exclusively played male characters – something that I had done as a child, but doing it on Livejournal and over AIM made it seamless and effortless in a way it never had been. My body – along with my own deep discomfort with it – just wasn’t as important as it had been before. In short: I came to experience digital contexts as “spaces” within which I could play with my own gender identity in ways that physicality had made difficult.

But that’s not to say that these spaces afford the performance of all kinds of gender equally. Not in my experience, and not in the experience of others. Digital “spaces” are profoundly gendered. Different kinds of technology are differently gendered. For a long time, the tech community – and all of its varied sub-communities – has been a boy’s club, and in many ways still is. The internet as a whole is still frequently and overwhelmingly a hostile environment for women.

Livejournal (and its smaller, more fandom-friendly offspring Dreamwidth), with emphases on messy journally feelings-having, has traditionally been considered more feminine than masculine (and has had a much higher percentage of female users than men), though again, it was in these places that I first began to open myself up to the feelings of being masculine. For the most part, in most of my digital spaces, I continue to feel more masculine than not, profoundly queer in spaces that afford fluidity in ways that my body does not, roleplaying wildly, picking up and discarding elements of performance as it suits me to do so.

Enter Pinterest.

At least in the US, Pinterest has come to be understood as gendered massively female/feminine/femme. As Nathan Jurgenson noted in his essay on Pinterest and feminism, this has resulted both in misogynist mocking and devaluing of Pinterest as a female/feminine digital space, and also in suggestions that the kind of femininity typically on display on Pinterest is itself problematic. In Bon Stewart’s terms, Stepford-Wife-y:

That’s the problem, Pinterest. You’re a grownup version of dress-up, of playing cotton-candy princesses. It’s fun. Play is healthy. But when we build broadly networked aspects of our public selves based largely on these tickle-trunk identities? Especially with stuff that we’ve lifted finders-keepers-style from other people’s equally aspirational magpie nests? We may eventually find ourselves with the identity equivalent of tooth decay.

So what’s included in this particular conceptualization of femininity? Recipes. Shopping. Interior decorating. Makeup. Nail polish. Jewelry. Gardening. Fashion. Granted, all things that men enjoy, but things that we nevertheless tend to associate with femininity. With being feminine. With being femme. With being a woman. God help me, as a scarily angry feminist and a binary-shredding queer, I associate them with those things.

Go look at my Pinterest boards again. I’ll wait.

It’s not play-acting. It’s not ironic. I genuinely love those things. I love looking for them, I love pinning them. Food porn and manicure ideas and makeup tutorials and houses much nicer than I will ever have and pretty dresses. The experience of first beginning to use the site was bizarre. It was unlike anything else I had experienced in a social media site; it was like putting on a digital dress. I could feel my gender shifting. And it was strangely liberating, as if I was – once again – in a space that was affording me the opportunity to play with an aspect of my gender that other digital spaces had not.

But I should also note that I pinned these things – that I curated what I saw and arranged my boards – according to the things the site put in front of me. According to where it sent me and encouraged me to go, in myriad subtle ways. I didn’t perform gender in a vacuum on Pinterest. I have never performed gender in a vacuum anywhere. My performance of gender on Pinterest is strongly influenced not only by my own gender identity but by the kinds of performances the site itself facilitates. And this facilitation – this affordance – is a result not only of the design of the site itself but of the ways in which the users use the site, which subtly influences further design.

So one of the things about which I think it’s important to note here is that it might be useful to think of affordances not as static instances of the possibilities created by design and interpreted by users but as ongoing dynamic processes, dialectics between designers and users. I don’t think this is by any means confined to digital contexts, but I do think that we can see especially marked examples of it in those contexts.

Finally, though, my point is digital spaces are not only gendered but are constructed in such a way as to afford different kinds of gender performance, all of which is highly situational, some of which may have no obvious outward significance to anyone but the performer. If our lives are augmented, if our experience of ourselves is augmented, our gender is also augmented. It isn’t something that purely informs the digital aspects of who we are; it is a dialectic as well. I believe I was genderqueer before I started roleplaying male characters with my fandom friends, but I also believe that the gender play in which I engaged within digital spaces informed my understanding of my gender as a whole, and of its fluid nature. The kinds of play I was able to do – the kinds of gender I was and am able to easily perform, to myself if to no one else – may be constrained or facilitated depending on the context. As is true of reality in general.

And apparently my gender-constructive playing isn’t done yet. Thanks, Pinterest.

omgggggggggg look at that mani

Sarah is wildly gender-fluid on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry

Comments 20

Jeremy Antley — April 5, 2013

A little additive to your argument above:

I think you are entirely correct to suggest that affordances of design are dynamic in their processes- especially in the context of user/designer 'dialectics'. While many look at Pintrest and think it conforms to a sort of perceived femininity, you have demonstrated that this framing of the site is more static than it really should be.

What's interesting to me is how 'pinning' can become part of the dialectics surrounding concepts like modernity or superiority, in addition to gendered ideals. For my own research on the immigration of Russian Old Believers to Oregon in the mid-60's, I've examined a recent Smithsonian article about the 're-discovery' of an Old Believer family in the Siberian wilderness in the 1970's. (http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/For-40-Years-This-Russian-Family-Was-Cut-Off-From-Human-Contact-Unaware-of-World-War-II-188843001.html)

Now what strikes me here is that the picture they provide on Karp & Agafia Lykov, one that describes them as wearing clothes given to them by Soviet geologists, can be 'Pinned' to one's Pintrest wall. Since I view this article as a means by which the modern is measuring itself against that of the 'backwards' Old Believers, the act of 'pinning' this picture can be seen as one of domination, or assertion of the superiority of the modern against that of the supposed 'backward'. (More on that here: http://www.peasantmuse.com/2013/02/pin-modern-on-old-belief.html) Some would definitely view this 'dominating' act as masculine, but I think, as your post suggests, that this is perhaps an oversimplification of the process.

So I think you are entirely correct to place Pintrest among a fluid dialectical process- one that goes beyond the surface and tackles issues related to the underlying power of constructive identities.

Pinterest and Playing Gender » Cyborgology | neologism | Scoop.it — April 6, 2013

[...] Pinterest and Playing Gender: A note: I’m using terminology like “digital space” and “online” in this piece, t... http://t.co/S02tZAnhVN [...]

QRG — April 6, 2013

'Digital “spaces” are profoundly gendered. Different kinds of technology are differently gendered'

Sure. But we disagree on how these arena are gendered. And the most 'hostility' I have experienced in digital 'spaces' has been from feminist women. One feminist blog 'community' even awarded me an 'honorary penis' for my treason against the fairer sex. I treasure it to this day.

I am currently writing a conference paper on tumblr and focussing on how it reinforces and showcases men's metrosexual 'display' in what we could say is very 'feminine' ways. Lots and lots of tumblrs are dedicated to beautiful pictures of tits and ass - men's tits and ass.

I'm not on pinterest or facebook. I love/hate twitter - but don't see a clear 'gendering' of twitter as a whole. It's too big and complex to define.

QRG

Evilagram — April 6, 2013

This used to be a blog about the disjunct between people's perceptions of virtual and physical reality. Now it's almost as if half the entries are about gender issues or short sighted social justice. Where did Cyborgology go so wrong?

whitneyerinboesel — April 6, 2013

sarah, i just want to say that i love this post--and i think the point you make about affordances being the result of a dynamic and dialectical process is spot on! :)

In Their Words » Cyborgology — April 7, 2013

[...] “There’s a stereotypical Pinterest user and I can’t escape the feeling that it is what I have bec...” [...]

Jenny Davis — April 7, 2013

Love that a highly gendered space becomes a space of gender fluidity through subjective use. Wonderful analysis here. I think this gets at a really important point--that the nature of technology is far from natural, but varies with the user's relationship(s) with it.

Friday Roundup: April 12, 2013 » The Editors' Desk — April 1, 2014

[…] “Like” labor; Facebook friends are real friends; playing gender on Pinterest; and why the “Red Sea” of equality on social media is inspiring, if […]