Apologies for the typos and the general lack of editing of this piece, I’m hurriedly tapping this out right before putting on the Theorizing the Web conference in a couple of hours.

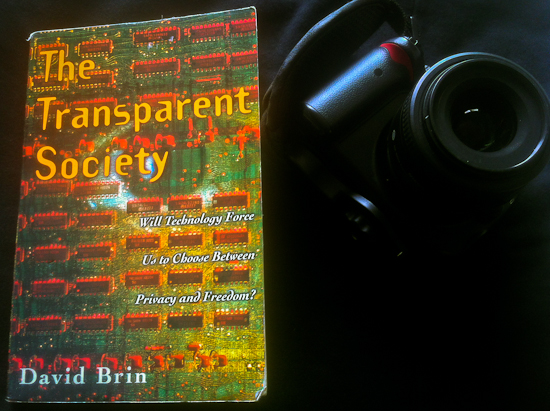

Nicholas Carr chose a great lead photo for his post yesterday critiquing the anti-digital-dualism argument put forth by myself and others on this blog. The image of a remote landscape evokes “wilderness”; well, it doesn’t “evoke”, it literally says “wilderness” right on it and the filename was “wilderness.jpg”. I think this image might be a fun way to illustrate one very fundamental disagreement Carr and I have. But before we can get there, I should spend some time replying to the various points in his post. Since Carr’s rebuttal to the digital dualism argument gets the digital dualism argument I have made wrong in some very fundamental ways, I’ll have to spend much of this post simply clarifying that; which is fine, reiterating things is a useful task. Though, what’s more fun than restating what’s already been said is jumping off into new directions, and hopefully we can do a little of that here, too, finishing with that lead photo.

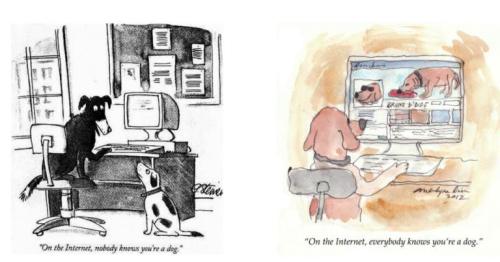

Carr begins by laying out the argument against digital dualism sustained on this blog, and spends much of the post dealing with me personally. He begins with a story about how the on and offline were once clearly separated, but, as web-access has become more widespread, they have blurred, and then says that’s the story we tell on this blog. That’s fundamentally not our argument. Here’s maybe where we went wrong: in my original post coining “digital dualism” I did say that the digital and physical are “increasingly enmeshed.” I regret that “increasingly,” a word I’m increasingly finding I overuse. I’ve always held that reality has always been augmented by various flavors of information, though my first blog post wasn’t clear on that. Since, I’ve been more clear that digital dualism has always been false, instead of being contingent on anything like network speed. PJ Rey has done great work on just this issue, and I’d encourage Carr to take that on as well. Thus, unlike the characterization on Carr’s blog, our position is that the digital dualism of the 90’s might be a bit more understandable, but was equally false.

Carr also mischaracterizes my IRL Fetish essay, saying,

Jurgenson’s real mistake is to assume, grumpily, that pretty much everyone who draws a distinction in life between online experience and offline experience is in the grip of a superiority complex or is striking some other kind of pose. That provides him with an easy way to avoid discussing a far more probable and far more interesting interpretation of contemporary behavior and attitudes: that people really do feel a difference and even a conflict between their online experience and their offline experience.

Carr states,

There’s no reason to believe that grappling with the online and the offline, and their effects on lived experience and the formation of the self, won’t also produce important thinking and art. As Sacasas implies, the arrival of a new mode of experience provides us with an opportunity to see more clearly an older mode of experience. To do that, though, requires the drawing of distinctions. If we rush to erase or obscure the distinctions, for ideological or other reasons, we sacrifice that opportunity

Let me, grumpily (lol), point out that I never claim that “pretty much everyone who draws a distinction” between on and offline experience are in the grip of a superiority complex. Because my argument is that they are different and are experienced differently. I even made a post, one that Carr cites, where I give a name to this view, “strong augmented reality”, and say it is a straw-person and I don’t agree with it. My argument is that there is a difference in being on Facebook and at a bar, war with drones and computers, sex physically co-present and through text messages. In my IRL Fetish essay I say,

To be clear, the digital and physical are not the same, but we should aim to better understand the relationship of different combinations of information, be they analog or digital, whether using the technologies of stones, transistors, or flesh and blood

Carr says I avoid discussing people’s different experiences of the on and offline, whereas in a post he cites I make clear,

Interaction on Facebook is different than at a coffee shop, but both Facebook and the coffee shop inhabit one reality

Carr does take on my categories of “strong” and “mild” digital dualism and augmented reality. Again, I create these in order to call out and remove the straw-people some have constructed in these conversations around digital dualism. It’s necessary to point out that digital dualists almost never see the digital and material as fully separate and not interacting. That’s a straw-person, as well is the idea that those supporting a synthetic, mixed, or augmented reality think there’s no difference between, say, Facebook and a coffee shop. No one thinks that either. Yet, there remains a very deep difference between those who do and do not see the on and offline as largely a zero-sum trade-off. Exactly what words we choose to talk about these very different positions is the semantic fun we are having going back and forth and figuring out, a project that has been inspiring, fruitful, and one Carr views as mostly irrelevant.

On Twitter, in op-eds, on this blog and others, in forthcoming papers, I’ve detailed many examples of very divergent ways of understanding the digital. I think the zero-sum perspective of the digital is starkly different than mine, especially as I laid it out in The IRL Fetish, but Carr is smart and if it’s still vague to him, it probably is for others, too, so I’m glad there’s lots of people who are excited to keep refining these conceptual categories and hopefully makes things more clear.

To do this, I implore thinkers to always and deeply take on the digital as comprising real people with real politics, histories, struggles, with real bodies and real feelings and so on. When we forget to do that, we can, for example, make that classic cyber-utopian mistake of seeing the Web as some new space separate from power, resistance, and embodiment (not something I’m accusing Carr of). I want these thinkers to also remember that our reality, even that solitary stroll on Cape Cod or in that wilderness scene from Carr’s post, is always augmented by various flavors of information, including the digital. Forgetting that, we can, for example, play the problematic and dangerous game or arbitrating who is more and less “real”, something I’ll come back to at the end of this post. Perhaps the terminology—strong, mild, dualist, interactionalist, synthetic, mixed, whatever—is vague, yes, let’s work on that, but the consistency in which people fail to do what I’ve asked for above, largely due to a zero-sum understanding of the supposed “on” and “offline”, is anything but vague but clear and persistent.

Carr concludes where I begin my IRL Fetish essay by saying, “we sense a threat in the hegemony of the online because there’s something in the offline that we’re not eager to sacrifice.” My reply is still my original argument: we’ve falsely constructed the categories “on-“ and “off-line” in order to tell the story that there is something virtual impinging on the real, allowing us to claim one’s own disconnection makes one more real. The insecurities around what is real, this obsession over authenticity, is a product of modernity in general and constructing “the virtual” provides an all-to-convenient shortcut to solve this modern dilemma by quelling one’s insecurities around their own authenticity. In any case, just to be clear, Banks, myself, and others are not “denying” the tension people feel between on and offline experience, as Carr states. Far from it, our entire projects are precisely about this tension.

Carr and I both are hearing people say that technology is impinging on the “real” (rarely articulated as such, but that’s the implication), and whereas Carr takes this pretty much at face value, I have the audacity to suggest what people say isn’t the full story, arguing that this isn’t an infringement on the real but the creation of the myth of the virtual to simultaneously deploy “the real” that one can then have access to (and often looking down on others still caught up in the “virtual”). This type of argument, that cultural forces are more complex than what might be seen at face value, does indeed make some people very mad, but that’s a pretty fundamental philosophical presupposition that neither of us are going to prove or convince each other of here. But dismissing this type of approach means also dismissing much psychoanalytic, critical, feminist, queer, structural, post-structural, postmodern, and many more theories. But let’s maybe save that discussion for over coffee? Let me conclude with a different disagreement.

I’ve spent most of this post just clarifying my previous arguments and listing what I think Carr missed or got wrong. This is probably pretty boring to almost everyone (though I kind of love it, sorry). Let’s end by briefly going off into a new direction for a moment, and it brings us back to that lead photo Carr used.

Carr states,

We should celebrate the fact that nature and wilderness have continued to exist, in our minds and in actuality, even as they have been overrun by technology and society.

Evgeny Morozov responds,

This idea of nature as separate from technology is pretty fundamental to why Carr and I see things so differently. This notion of “the natural” as something to cherish is, to me, fraught. This wilderness landscape isn’t “natural”. First, that scene is of nature that has been carved out, made “natural” by being demarcated, defined against un-natural environments of roads and buildings. By being not-unnatural it’s unnatural, curated and maintained to best simulate the real. I love hikes, but even back country routes are highly developed, pre-planned, simulated. Further, even the most remote areas are understood as not-developed, still understood in the terms of the developed. Parallel to our discussion here, this is my argument in The IRL Fetish essay, too,

When Turkle was walking Cape Cod, she breathed in the air, felt the breeze, and watched the waves with Facebook in mind. The appreciation of this moment of so-called disconnection was, in part, a product of online connection.

We always understand nature through technology, most abstractly through the technologies of social norms or language or more concretely through transportation routes, architecture, and most recently, understanding a hike without cell-signal as not-Facebook. As PJ Rey has convincingly argued, there is no logging off.

There is no “natural”, these spaces are understood and appreciated through the context of social standpoint, culture, politics, history, conflict, domination, resistance, embodiment, affect, and everything else. “Nature” is always a social construction, and appeals to it should be followed by ‘whose nature’? Or, as I frame it in these discussions about digital-experience, who benefits when one person anoints themselves a worthy arbiter of what set of experiences is more or less real?

Nathan is on Twitter [@nathanjurgenson] and Tumblr [nathanjurgenson.com].

Leading up to

Leading up to