Watching the ideas materialize, disseminate, get knocked down and picked back up all in near real time is either the greatest advantage digital dualism theory has, or its biggest downfall—its best feature or worst flaw. Or both. Personally, I’m having a blast, even if it’s a bit of a distraction from my dissertation. It’s the spirit of this blog, a rare academic space to try ideas out, work on them, debate them, meet new people, and watch the idea, one hopes, get better and stronger. Or sometimes no one cares and we move on. This is what I love about my colleagues on Twitter (I’ll never type the word tweeps), this blog, and the Theorizing the Web conference.

Watching the ideas materialize, disseminate, get knocked down and picked back up all in near real time is either the greatest advantage digital dualism theory has, or its biggest downfall—its best feature or worst flaw. Or both. Personally, I’m having a blast, even if it’s a bit of a distraction from my dissertation. It’s the spirit of this blog, a rare academic space to try ideas out, work on them, debate them, meet new people, and watch the idea, one hopes, get better and stronger. Or sometimes no one cares and we move on. This is what I love about my colleagues on Twitter (I’ll never type the word tweeps), this blog, and the Theorizing the Web conference.

The drawback is that the theory is still piecemeal, undercooked, not fully developed. I can understand why some folks who are used to ideas arriving “fully formed” in a book are being caught off-guard. Indeed, as far as theoretical discussions go, this digital dualism idea has emerged and progressed in a way I personally have not seen before. It started when I, some random graduate student, tossed out the idea on a mostly unheard of blog. But then lots and lots of smart people joined in, as Whitney has thoughtfully summarized; with additions, critiques, and countless examples, discussions are getting more nuanced, longer papers are being written, conference presentation are being given, people keep saying the word “book”. Kim Witten said it well earlier this week,

It isn’t even an argument on the internet, really. It is a bunch of people with different perspectives figuring out something new and exciting. I want to be a part of that. I’m fascinated by it. It’s why I’m in academia

Right on! In this spirit, let me express a frustration and write, mostly for myself, about how I see this debate progressing and why I want to shift directions a bit. I’ll conclude by asking for some help. It started when an especially honest tweet fell out of me last week:

When I began graduate school and started to think conceptually about the Internet, one of the first things that annoyed me was people saying “real” to mean not-the-Internet. “Real” has a few different formal definitions and even more uses in practice. To make it too simple, I want to conceptually split questions of the “real” as a statement that something actually exists as a thing versus “real” to describe that which is more genuine, authentic, or true. Of course, these are deeply related concerns, but the primary focus on one or the other leads to different types of digital dualism critiques. I’ve always wanted to integrate these, but have been so far unsuccessful and thus want to change strategy a bit and pull them apart.

Ontological digital dualism is primarily concerned with “what exists”: are the digital and physical separate “things”? in different “realities”? “spheres”? are bits made of atoms? what about photons? I pointed a path towards this line of inquiry here by delineating four ontological positions based on strong versus mild digital dualisms and augmented realities. There has been significant debate on these terms, but Nick Carr, as much as we disagree, has always been right that the terms being used here are less than clear. Carr is right to say that, at the ontological level, almost everyone agrees that the digital has different and new properties and interacts with the rest of this thing we call reality.* This is what drives Nick Carr to say that the digital dualism critique isn’t useful. At the ontological level, yes, he makes a good case that we on this blog haven’t been overly convincing, though, I still think he is wrong. Evgeny Morozov has been especially persistent in taking Carr on, and we Cyborgologists are collectively working towards a convincing response—hold tight, we’re graduate students learning new literatures and writing dissertations on other things, so give us a minute. But something happened where these ontological questions have begun to dominate my own thinking, and I’d like to switch gears.

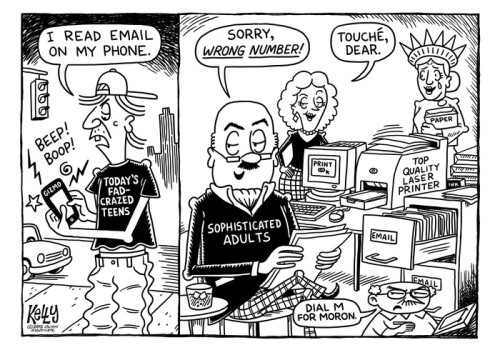

To get at this switch, let’s think about how it can possibly be the case that the ontology arguments aren’t (yet?) semantically clear, but, meanwhile, cases of digital dualism (“these kids with their Facebooks are trading reality for the virtual!”) seem so stark, so obvious. The situation can’t be as vague as Carr wants his readers to believe given the intuitive obviousness of digital dualism that so many people have latched onto. I think I have at least a partial answer for this.

For me, the strategy to move forward is to place ontology largely on the back-burner for a bit and focus on a somewhat different critique of digital dualism. The digital dualism I want to focus on is two-fold:

First, I want to refocus the definition of digital dualism to the moments where people downplay the role of the digital when speaking of something they think is material (wrongly called “real”) as well as downplaying the role of the material when speaking of something they think is primarily digital (wrongly called “virtual”). Regardless of your position on “reality”, this is digital dualism that underestimates the enmeshment of information and materiality, leading to ideas like Facebook comprises “virtual” rather than “real” friendships, that there is some “second self” that you inhabit online, and so on. Over the dinner table, in blog comments, in op-eds, in research papers, people often simply forget the material when talking about the digital and the digital in the material. Yes, people may almost never say the Internet is some distant other universe, but people do often overstate how distant and unrelated the material and the digital are. Those holding this digital dualist, zero-sum, conception of the on and offline are the ones surprised by research showing that those who do more online tend to also do more offline, opposed to the idea that people are trading “real life” in favor of living on Facebook.

Thus, digital dualism is the tendency to see the digital and material as too distinct, rather than enmeshed, consistent with the definition of the term I worked with one website to create:

n. The belief that online and offline are largely distinct and independent realities.

Second, I want to refocus on the question of how digital dualism—this tendency to underestimate digital-material enmeshment—often clears a clean path towards the claim that one (usually, but not always, the material) is more real, deep, human, and true. Not ontology, these are cultural value statements based on the idea that the on and offline are distinct rather than enmeshed.

My most passionate expression of this concern is my IRL Fetish essay where I argue that calling the digital “virtual” lets one simultaneously claim that which is not digital is “real.” It allows one to say that there is a crisis of the real, that it is disappearing in precisely the same moment that we are obsessed over it.** The real isn’t going away, what people are doing on Facebook is real and has everything to do with the offline. I end up concluding that that those asking us to disconnect and log off are too optimistic, just like Facebook is filled with the offline, the so-called offline, like Carr’s wilderness and Turkle’s Cape Cod, is similarly saturated with the online. Because I’m a giant dork, this is the argument that drives my interest. This is the anti-digital dualist, augmented, synthetic perspective that views information-saturation in what people call “offline” as well as the material, human, and political in what people call “online”.***

I very much welcome all the work people are doing on ontological digital dualism. I’ll drop by, promise.

I’d like to close with a question: do we need names for these different digital dualism perspectives? If so, what to call them? I’m asking, and would love to discuss this more in the comments.****

First, there’s ontological digital dualism theory that asks about what exists and is concerned with atoms and bits and photons and realities and spheres; Hayles, Haraway, and Latour seem like obvious starting points. I think this is a fine name for this perspective.

Next, there’s digital dualism theory that asks if a perspective or an idea or an articulation has or has not underestimated the enmeshment of the digital and the material.

Third, there’s the concern over the value statements that derive from the dualistic conceptualization, such as people fetishizing the digital as some new space impossibly pulled apart from messy material realities; or, opposite, but born of the same dualist fallacy, fetishizing the material as more deep, human, or true, what I like to call “the IRL fetish” or “digital dehumanization.”

So, what to call these last two concerns? In asking, I’m doubling down on the idea that this real-time and collaborative theorizing is a terrific feature of digital dualism theory, not a flaw.

Nathan is on Twitter [@nathanjurgenson] and Tumblr [nathanjurgenson.com].

*There are some who can make great arguments that “digital” and “material” aren’t words we should even be using, but let’s bracket that discussion for a moment since I’ve yet to fully digest this criticism, though I did write a head-scratching response.

**One might note the significant and intentional argumentative overlap between my point about the so-called disappearance of the real with Foucault’s similar point about sexuality in his “repressive hypothesis” throughout “History of Sexuality: Vol I”.

***Confession: I’m much, much more into the “digital dualism” theory than “augmented reality”.

****Again, understanding that the different perspectives are never cleanly separated but always overlapping to more or less of a degree at different times.

I’m having a blast reading all of the recent posts about

I’m having a blast reading all of the recent posts about